|

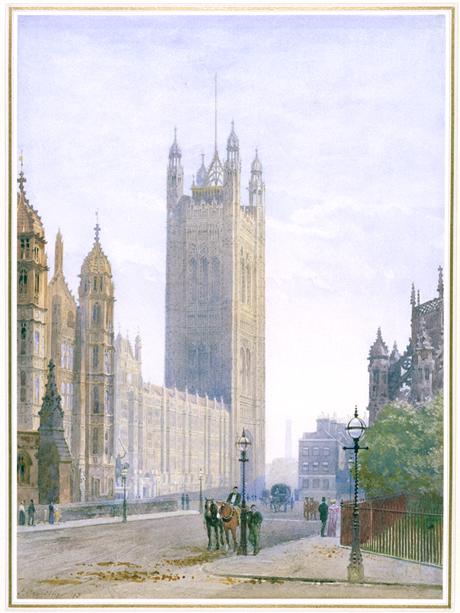

| The Victoria Tower of the Houses of Parliament seen from Parliament Square John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

INTRODUCTION

London has long been more than just a city—it is a symbol of power, culture, and endurance. Samuel Johnson’s timeless quote perfectly captures the city’s eternal magnetism.

To walk the streets of London is to walk through centuries of history layered upon each other: medieval churches stand beside Victorian warehouses, Georgian squares, and modern skyscrapers.

Every corner reveals a story, and perhaps no medium captures that story better than art.

During the Victorian Age (1837–1901), painters turned their eyes to London with a renewed passion. This was the era of Queen Victoria and the height of the British Empire. It was also a time of rapid urban change—industrialization, population booms, new railways, and the birth of modern London. Amid this transformation, artists used their canvases to preserve not just buildings, but moods, moments, and the pulse of life in the capital.

Victorian paintings of London offer us more than mere landscapes; they are visual time machines. They record the grandeur of landmarks like the Palace of Westminster, the bustling energy of Piccadilly Circus, and the everyday realities of ordinary streets in Stepney or the Strand.

They show us how Victorians saw themselves, their city, and their empire. Today, these works hang in prestigious galleries such as the National Gallery, Tate Britain, and the Museum of London—reminders of a city both eternal and ever-changing.

London as Seen Through the Artist’s Eye

London in the 19th century was a city of contrasts. Wealth from the empire poured into the West End, financing stately homes, theaters, and department stores. Yet at the same time, poverty spread through the East End, where families crowded into small tenements. Artists of the Victorian Age captured both realities: the elegance of grand boulevards and the gritty details of working-class neighborhoods.

Painters like J.M.W. Turner, James Whistler, George Hyde Pownall, and John Crowther brought their own perspectives to London’s streets and skyline. While Turner turned the Thames into a misty, almost spiritual vision, Crowther meticulously documented the details of streets that were vanishing under modernization. Each painting is a lens, allowing us to see London as its inhabitants did more than a century ago.

John Crowther: The Painter of Lost Streets

One of the most important artists for understanding Victorian London is John Crowther (1837–1902). Crowther was not just a painter; he was also a documentarian of change. Commissioned by architects and preservationists, he created hundreds of watercolors of streets, churches, and buildings before they were demolished to make way for new developments. His work combines technical precision with emotional depth, offering both accuracy and atmosphere.

Crowther’s watercolors are invaluable because they show us places that no longer exist. Streets around the Strand, alleys in Stepney, and forgotten corners of Westminster live on in his paintings. He did not only paint structures—he painted the life around them: people walking in the rain, shopkeepers arranging their goods, and children playing in the street.

The Victoria Tower of the Houses of Parliament (1893)

One of Crowther’s most iconic works is his painting of the Victoria Tower, part of the Palace of Westminster, completed in 1893.

The Victoria Tower rises proudly above Parliament Square, symbolizing authority and continuity. In Crowther’s painting, the tower is rendered with calm majesty against a soft, cloudy sky. Figures in late 19th-century dress walk across the square; horse-drawn carriages roll past. Nothing is hurried, yet everything suggests the quiet dignity of a capital city at the heart of an empire.

This image is not just about architecture—it is about atmosphere. Crowther captures the sense of power that the Houses of Parliament radiated in Victorian London. At a time when Britain ruled over a quarter of the world’s population, Westminster stood as the ultimate emblem of governance and empire.

Junction of Howard Street and Norfolk Street, London

John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}}

Howard Street and Norfolk Street, Strand (1880)

John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}}

In stark contrast, Crowther’s 1880 painting of Howard Street and Norfolk Street near the Strand is intimate and human.

The painting depicts a junction of narrow lanes, lined with modest shops and tall, narrow houses. Unlike the grandeur of Westminster, this is the London of daily life: tradesmen, clerks, and working-class families.

The detail is astonishing—shop signs, windowpanes, and paving stones are all painted with care. This was a world that was soon to disappear, demolished to make way for new roads and railway expansion. Crowther’s painting serves as both a memory and a warning: the progress of the city was unstoppable, but at the cost of its older character.

Today, if you walk near the Strand, you will find no trace of Howard or Norfolk Streets. Yet thanks to Crowther, these vanished corners remain alive on canvas.

King Street, Stepney, London {{PD-US}}

John Crowther, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

King Street, Stepney

John Crowther, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

Crowther’s painting of King Street in Stepney transports us to East London, a district known for its working-class communities.

The scene is modest but powerful: small terraced houses, women in long skirts chatting, children playing, men carrying goods.

Stepney was far from the wealth of the West End. It was a place of dockworkers, factory laborers, and immigrants seeking a better life. Crowther’s painting does not romanticize poverty, but it also does not present it as bleak.

Instead, it shows resilience and community spirit—the human side of Victorian London that often goes unnoticed.

George Hyde Pownall: Lights of the West End

While Crowther documented the quieter and older corners of London, George Hyde Pownall (1866–1932) captured its lively heart. A master of atmosphere, Pownall is best known for his street scenes glowing with lamplight and activity.

One of his most famous paintings, Piccadilly Circus, depicts the West End’s energy. Unlike Crowther’s calm watercolors, Pownall’s canvas buzzes with life. Crowds surge across the square, horse-drawn cabs jostle for space, and gas lamps flicker against the night sky.

Piccadilly Circus was then, as it is now, a hub of entertainment. Theaters, restaurants, and shops attracted people from across the city. Pownall’s work captures the sense of modernity—the electric excitement of a metropolis moving at full speed.

Victorian London: A City of Contrasts

The contrast between Crowther and Pownall reflects the deeper reality of Victorian London itself. This was a city of immense wealth and crushing poverty, of tradition and innovation. On the one hand, London was the glittering capital of the British Empire, enriched by global trade. On the other, it was home to slums, overcrowded housing, and grinding labor.

Victorian paintings reveal both sides. The monumental architecture of Westminster represented national pride, while paintings of Stepney or the Strand revealed the everyday struggles of ordinary people. Together, these artworks create a balanced picture of a complex city.

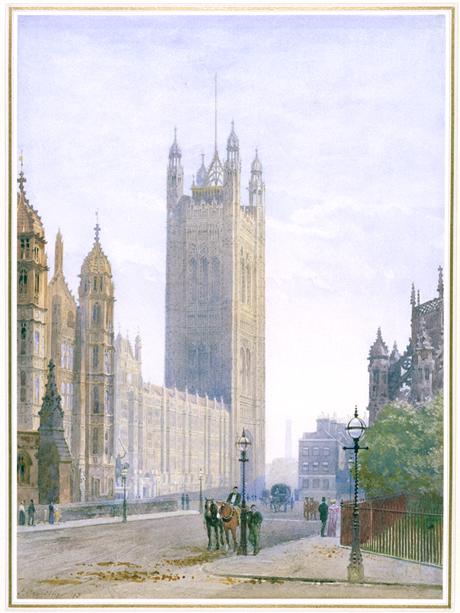

|

| The Victoria Tower of the Houses of Parliament seen from Parliament Square John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Influence of the British Empire

No discussion of Victorian London is complete without considering the British Empire.

Trade routes from India, Africa, and the Americas flooded the capital with goods: tea, spices, textiles, and timber. The wealth of empire funded the city’s expansion, its grand boulevards, and its cultural institutions.

Yet empire also meant inequality. While fine furniture and fashionable clothes filled West End homes, the East End remained overcrowded and underpaid.

Paintings from this period, consciously or not, reflect this divide.

The elegance of Westminster or Piccadilly is inseparable from the global network of labor and trade that sustained it.

Victorian Art as a Time Capsule

What makes Victorian paintings of London so compelling is their role as historical records. Photography was still in its early stages, and artists provided the most vivid visual accounts of the city. Through brushstrokes, we see not only buildings but also weather, fashion, transport, and social life.

We can sense the fog rolling over the Thames, the clatter of carriages on cobblestones, the rustle of skirts in busy markets. These are details that history books cannot fully capture but which paintings preserve in living color.

Where to See Victorian Paintings of London Today

For anyone eager to experience these works firsthand, London’s galleries and museums offer unparalleled opportunities:

The National Gallery—home to masterpieces by Turner and Whistler, offering sweeping visions of London’s river and skyline.

Tate Britain showcases Victorian art in all its variety, from Pre-Raphaelite portraits to urban landscapes.

The Museum of London—a treasure trove of paintings, prints, and artifacts telling the story of the city’s growth.

Walking through these galleries is like walking through the streets of Victorian London itself.

Junction of Howard Street and Norfolk Street, London

John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}}

John Crowther, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons {{PD-US}}

Conclusion: London Eternal

Victorian paintings of London remind us of something profound: cities are alive.

They grow, change, and sometimes forget their past—but art remembers.

Through Crowther’s detailed watercolors, we see streets that no longer exist.

Through Pownall’s glowing canvases, we feel the energy of Piccadilly a century ago. Through Turner and Whistler, we glimpse the Thames as both a working river and a poetic muse.

London was, and remains, a city of contrasts—grandeur and poverty, tradition and progress, stillness and movement. This complexity is what makes it endlessly fascinating, both to artists and to those who love art.

So perhaps Samuel Johnson was right: if a man is tired of London, he is tired of life. For in London, and especially in the paintings of its Victorian age, we find all that life can offer—beauty, struggle, history, and the enduring spirit of one of the world’s greatest cities.