|

| Mario Varvogli Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Painted around 1919 in Paris, Amedeo Modigliani’s “Portrait of Mario Varvogli” is an oil on canvas typically catalogued at about 116 × 73 cm and recorded today as being in a private collection. The painting is sometimes noted as unsigned, with size and title variants across the literature—common issues for Modigliani’s late portraits.

The association with Marios Varvoglis, a composer active in early-20th-century Paris, is echoed by related drawings—such as Mario the Musician—which strengthen the identification of the sitter within Modigliani’s circle.

Historical context: Modigliani at the end of the 1910s

By 1919, Modigliani had entered the final, feverish stretch of his career. He was living in Paris, painting intense, economical portraits and nudes while struggling with ill health; he would die in January 1920. The late portraits, including “Mario Varvogli,” bear the distilled hallmarks of his School of Paris modernism—elongated forms, attenuated necks, sculptural faces, and a rhythm of line that seems carved more than painted.

This late-period compression—less fuss, more inevitability—suits a sitter like Varvoglis, a musician in Modigliani’s creative orbit. The Paris of 1919 was rebuilding after the war, and Montparnasse remained a transnational studio for painters, poets, dealers, and composers. Modigliani’s portraits from these months act like visual calling cards for that milieu: friends, patrons, models, and fellow artists captured with a candor that reads as both stylized and psychological.

|

| Mario Varvogli Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

What you see: composition, line, and color

-

Elongation and simplification. Modigliani trims naturalistic detail to emphasize the silhouette and the oval schema of the head.

-

Economy of palette. Late portraits favor a restricted set of earths, blue-greens, and muted reds, with chroma dialed back to let contour and proportion do the expressive work.

-

Carved contour. His line carries the memory of years obsessed with stone carving. Faces are modeled with planar simplicity, while a decisive dark outline defines the sitter’s figure against a shallow backdrop.

“Mario Varvogli” reads like a conversation piece in this language: the sitter is individuated (hands, posture, and the set of the head imply temperament) yet abstracted into Modigliani’s timeless type.

|

| Mario Varvogli Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Who was Mario/Marios Varvoglis?

Marios Varvoglis (often rendered “Mario Varvogli” in French sources) was a Greek composer who studied and worked in Belgium and France before returning to Greece.

He moved in avant-garde circles in Paris, which plausibly brought him into Modigliani’s orbit around 1919–1920. Drawings such as Mario the Musician corroborate his presence in the artist’s portrait roster.

Cataloging and provenance notes

The painting is included in multiple catalogue listings that note it as unsigned, record dimension variants, and place it in a private collection. Such discrepancies are typical in Modigliani scholarship, where several catalogues raisonnés and rival research projects coexist and sometimes disagree.

Because the work is in private hands and not attached to a recent public sale, hard provenance beyond published references is limited. Some sources casually cite “Christie’s London” as an image credit, but no corresponding sale is listed in public results, making it unlikely that the painting has appeared in a major auction in recent decades.

How it sits in Modigliani’s portrait canon

“Mario Varvogli” belongs to the artist’s late portraiture, which includes depictions of dealers, poets, and close companions. Compared with the earlier, rougher portraits from 1915–1916, these 1919 works tend to be more rhythmically unified and less descriptive. That correspondence between music and measure is especially fitting for a composer like Varvoglis: the measured elongations and the cadence of line echo the idea of a score expressed in paint.

Condition, authenticity, and why Modigliani is tricky

The Modigliani market is notoriously complicated by forgeries. Even major museum shows have triggered authenticity audits, and seizures of fakes have made headlines in the last decade. This climate doesn’t diminish the value of authentic works; rather, it amplifies the premium on thoroughly documented examples.

|

| Mario Varvogli Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Market value: What is “Portrait of Mario Varvogli” worth?

There is no recent public auction price for this specific painting. It is listed as a private collection, and no sale result for this exact title appears in major auction archives.

Top-of-market benchmarks

-

Nu couché sold at $170.4 million in 2015, the artist’s auction record.

-

Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) sold for $157.2 million in 2018, the highest price ever achieved at Sotheby’s.

These are reclining nudes, which belong to a higher price tier than portraits.

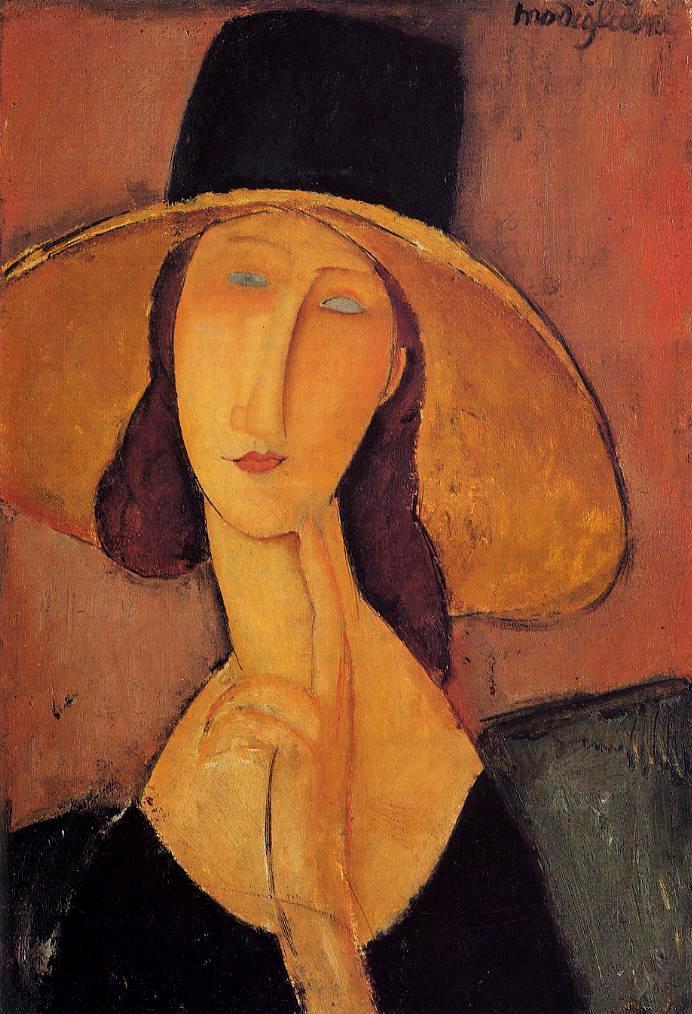

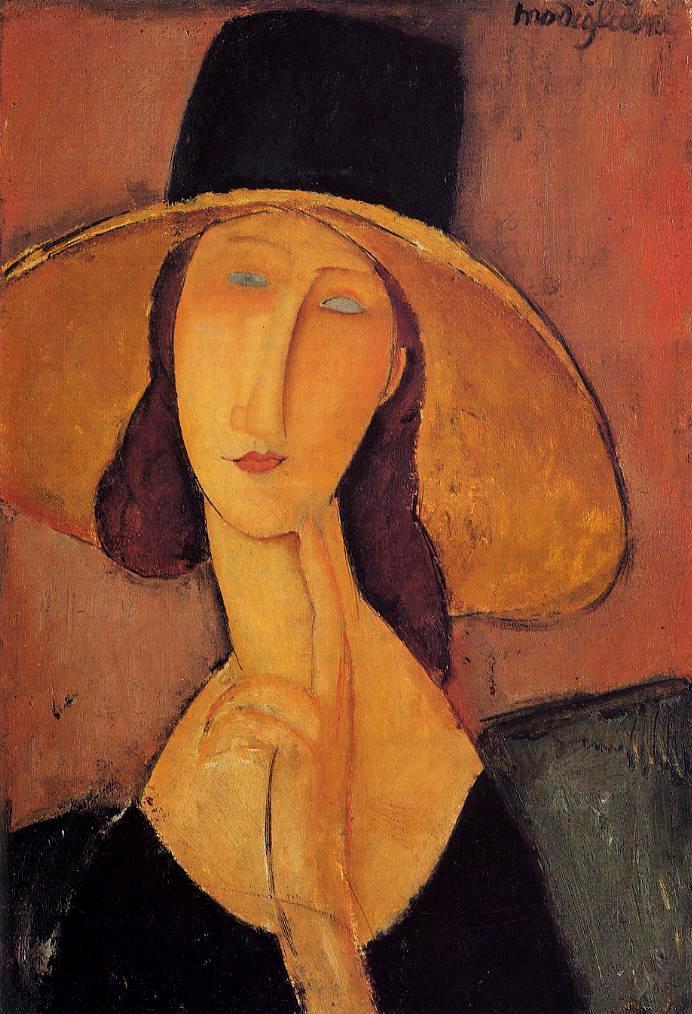

Jean Hebuterne with large hat

Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

Portrait comparables

Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

-

Jeanne Hébuterne (au chapeau), a 1919 female portrait, realized £26.9 million in 2013. Female portraits of Jeanne command premium pricing compared with male portraits of acquaintances.

-

Portraits of dealers or notable figures have sold from the low millions up to the teens/twenties of millions, depending on quality and provenance.

A reasoned value range

Considering the date (1919), scale (large), sitter recognition (moderate), and the importance of authentication, the painting would likely be valued in the mid-eight figures in USD if offered with full documentation. A cautious but plausible band would be $10–30 million, with the upper end achievable if condition, provenance, and scholarly acceptance are particularly strong.

Why collectors care

-

Late-career synthesis (1919).

-

Connection to the musical avant-garde.

-

Large-format oil (more desirable than small boards).

-

Relative rarity of named male cultural figures in his late portraits.

Final thoughts

“Portrait of Mario Varvogli” is a concise statement of Modigliani’s late style: an art of linear music, perfectly suited to a musical sitter. While it lacks the spectacle (and higher price tier) of the famous reclining nudes, it embodies the qualities that make Modigliani enduring—economy of means, sculptural presence, and a tender severity that turns individuals into icons.