|

Vincent van Gogh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Irises—Getty Center—Los Angeles |

"Discover Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Irises’ (1889)—an iconic masterpiece of vivid color contrasts, expressive brushwork, and textured impasto, painted in Saint-Rémy and sold for a record $53.9 million at Sotheby’s."

Vincent van Gogh’s “Irises” (1889) is one of the most celebrated flower paintings in art history—and one of the most famous paintings ever sold at auction.

Created shortly after his arrival at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, the work is a dazzling showcase of color mastery, expressive brushwork, and compositional intelligence.

It has also achieved iconic status in the art market, once setting a world record for a painting’s sale price.

The Scene and Setting

Van Gogh painted Irises in the garden of the asylum during the spring of 1889. At the time, he was seeking recovery from a mental health crisis, yet his work from this period is vibrant, deliberate, and remarkably life-affirming. The composition shows a dense bed of irises, their long leaves and twisted stems surging upward in a lively rhythm, punctuated by a single pale bloom among the sea of blue-violets. The dimensions are approximately 74 × 94 cm, making the canvas large enough to immerse the viewer in its tangle of forms and colors.

Color: Complements in High Voltage

Van Gogh’s genius for color in Irises lies in his use of complementary contrasts. The dominant blooms are painted in a range of violet and blue tones, set against yellow-green leaves and touches of rusty orange in the soil. This pairing of cool and warm opposites makes each color more intense: the violets seem more saturated when seen beside the greens, while the earthy orange notes make the greens fresher and more vivid.

The single white iris is a masterstroke. It functions as a visual pivot point, providing relief from the saturated palette and drawing the eye across the composition. Its pale tones also make the surrounding colors appear deeper and more luminous. Van Gogh’s approach here reflects his belief that color relationships, not isolated hues, carry the emotional force of a painting.

The blues and violets themselves are not straight from the tube; Van Gogh often mixed blues with reds to achieve rich, vibrating purples. These colors have a subtle instability—they shift with light and surrounding tones, lending the work a living quality. The result is a chromatic “chord” rather than a single dominant note, creating depth without relying on traditional perspective.

Brushwork and Texture

|

Vincent van Gogh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Irises—Getty Center—Los Angeles |

One of the most striking qualities of Irises is its directional brushwork. Van Gogh applies paint along the contours of leaves and petals, allowing stroke direction to reinforce form. This is not just decorative: the brushstroke becomes the shape, giving the painting its structural backbone.

The texture is pronounced, thanks to Van Gogh’s liberal use of impasto — thick paint that stands up from the canvas. This technique catches light in different ways as you move past the painting, creating a subtle shimmer and physical presence. Even the soil beneath the flowers is given life through short, energetic strokes, so that no area of the painting feels static.

Landscape Thinking in a Close-Up View

Although Irises might be classified as a floral still life, it’s composed like a landscape in miniature. Van Gogh has cropped the scene tightly, eliminating the horizon and focusing attention entirely on the flower bed. This approach is characteristic of his late landscapes, which often present a compressed, forward-pushed view rather than a deep vista.

The arrangement feels like a fragment of a larger world—flowers cut off at the edges imply continuity beyond the frame. The result is a painting that feels both intimate and expansive, as if the viewer is kneeling right in the garden.

Compositional Intelligence

Van Gogh balances wildness and order. The tall, spear-like leaves give a vertical rhythm, while the rounded petals add softer, scalloped counter-shapes. The line of irises flows laterally across the canvas, creating a frieze-like composition. Into this rhythm, he inserts the contrasting white iris, which acts like a bright accent note in a musical score.

This structure keeps the viewer’s eye moving, preventing the dense subject from becoming visually chaotic.

Technique and Material Choices

The violets in Irises were often mixed from red and blue pigments rather than purchased as ready-made purples, giving them a distinct, hand-crafted quality. The thick paint application required careful timing: layers needed to dry enough to avoid unwanted blending but not so much that they lost cohesion. Van Gogh’s control over these variables is evident in the crisp edges of some leaves and the deliberate blending in others.

Comparisons with Other Masterworks

To understand Irises more deeply, it’s useful to compare it with other major works by fellow masters.

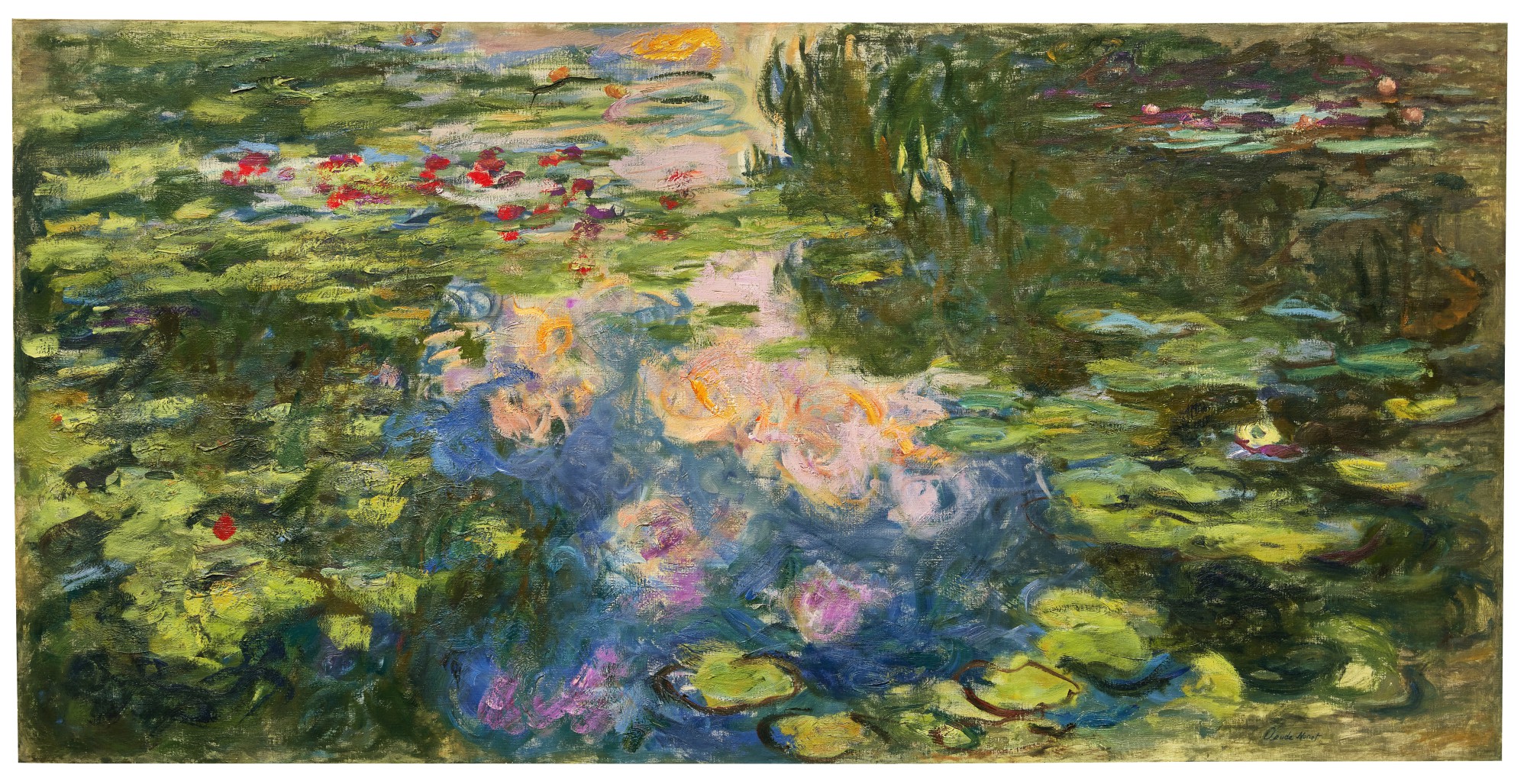

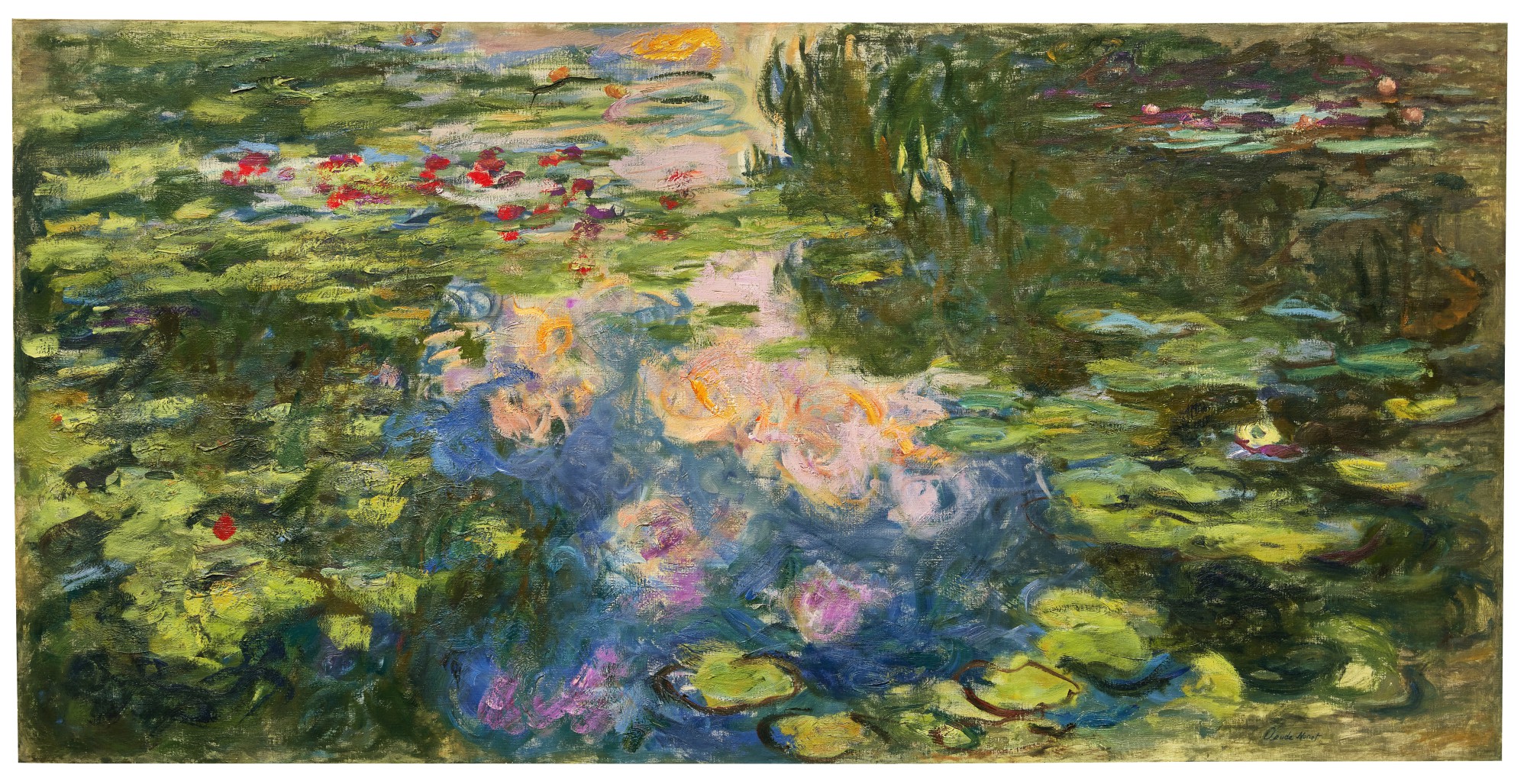

Claude Monet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Water-Lily Pond—Claude Monet

1. Claude Monet’s “Water Lilies” (1914–26)

Water-Lily Pond—Claude Monet

While Monet’s late Water Lilies series also focuses on a garden subject, the effect is entirely different. Monet’s brushwork is softer, his colors more atmospheric, with greens, blues, and lilacs dissolving into one another.

His compositions suggest endless, horizonless space, inviting the viewer into a serene immersion. Van Gogh’s Irises, by contrast, is sharper and more graphic, with defined contours and heightened color contrasts. Monet dissolves; Van Gogh energizes.

Paul Cézanne, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mont Sainte-Victoire

2. Paul Cézanne’s “Mont Sainte-Victoire” (various versions, 1880s–1900s)

Paul Cézanne, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mont Sainte-Victoire

Cézanne’s repeated studies of Mont Sainte-Victoire are exercises in constructive form, built from small, interlocking strokes that create a solid, architectural feel.

While Van Gogh’s brushwork is directional and emotive, Cézanne’s is modular and stabilizing. Both rely on shifts between warm and cool tones, but Cézanne’s are tempered while Van Gogh’s are amplified. Where Cézanne seeks equilibrium, Van Gogh embraces vibration.

Why “Irises” Resonates

-

Simplicity of subject: A bed of irises becomes a stage for exploring intense color relationships.

-

Tactile immediacy: Thick, directional paint makes the image physically present.

-

Compositional intelligence: A cropped view, rhythmic shapes, and a key tonal accent (the white iris) give visual cohesion.

-

Emotional vitality: Despite being painted in an asylum, the work radiates energy and delight in nature.

Auction History and Record Price

Irises became a sensation not just for its artistry but for its market performance. On November 11, 1987, at Sotheby’s in New York, it sold for a hammer price of $49 million. With the buyer’s premium added, the total came to $53.9 million, setting a world auction record for a painting at that time. The buyer, Australian businessman Alan Bond, faced financial difficulties afterward, and the painting was eventually acquired by the J. Paul Getty Museum in March 1990. The Getty has never disclosed what it paid.

Final Reflection

Irises is both an intimate flower study and a bold landscape statement. Its color harmonies are electric, its brushwork palpable, and its composition perfectly balanced between order and organic flow. In this single canvas, Van Gogh transforms a patch of garden into a symphony of contrasts and rhythms. That such a personal, concentrated view could command $53.9 million at auction speaks to its enduring power—not just as a work of art, but as a universal expression of vitality.