Introduction: The Allure of Watercolor in Portraits

|

| Portraiot of a Lady Watercolor on ivory John Smart, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

This quality makes watercolor portraiture uniquely suited to capturing fleeting expressions, subtleties of skin tone, and the essence of character.

While watercolor was historically used for sketches, botanical studies, or landscapes, many master artists elevated it into a respected portrait medium. Its accessibility and simplicity—requiring only pigments, water, and paper—made it both democratic and demanding.

Easy to begin but difficult to master, watercolor portraiture challenges the artist to balance control with spontaneity.

In this essay, we will explore the qualities of watercolor as a portrait medium, analyze seven significant public domain watercolor portraits, discuss their valuation and display, and provide guidance on how to achieve mastery in this delicate yet powerful art form.

The Easiness of Using Watercolor in Portraiture

Watercolor is often regarded as the most approachable medium for beginners. Its basic tools are inexpensive and portable. A set of pans or tubes, a few brushes, and good paper suffice.

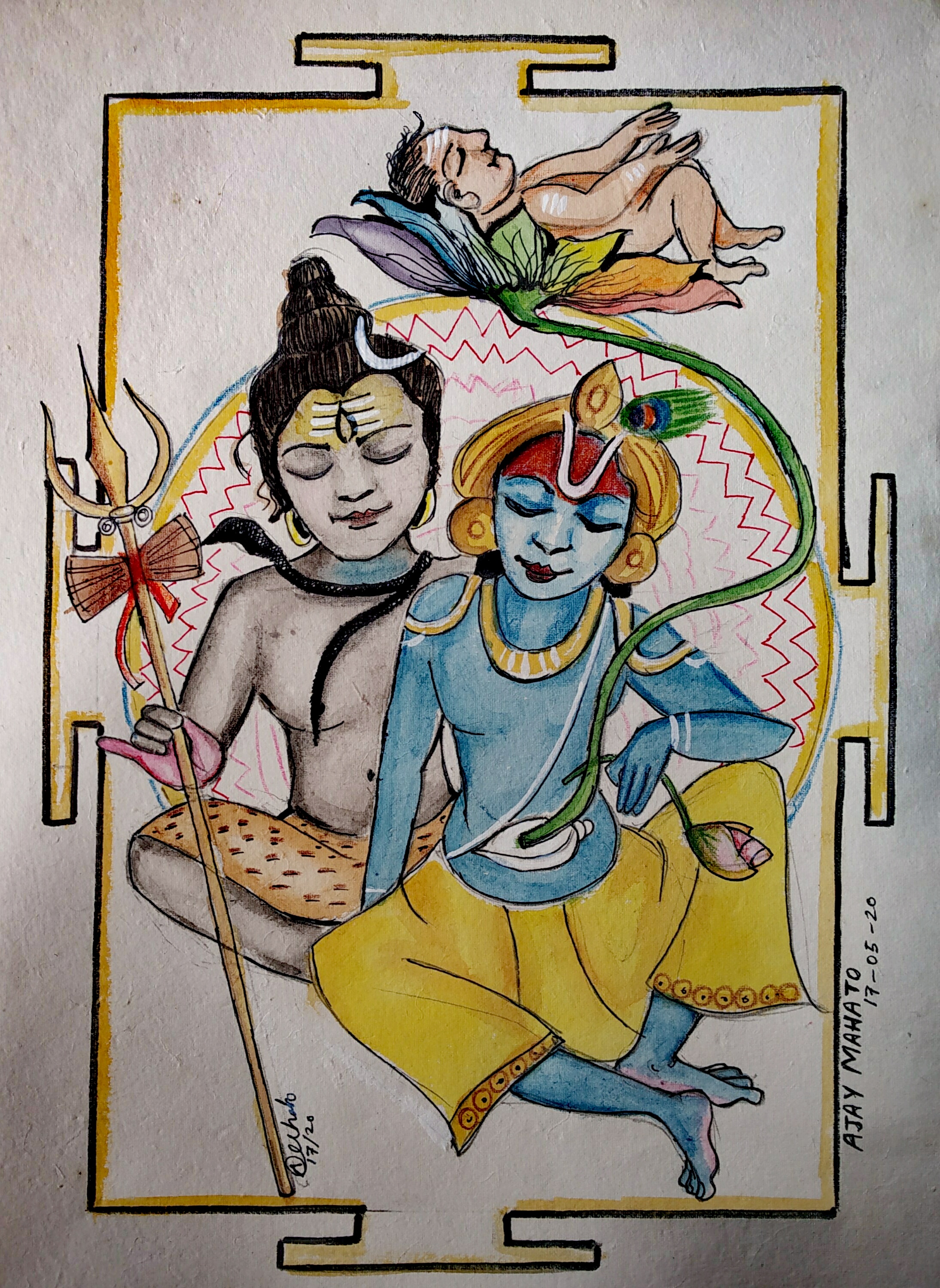

Harihar watercolor on paper

Nayan j Nath, CC BY-SA 4.0,

via Wikimedia Commons

Unlike oil paints, there is no need for solvents or long drying times; unlike acrylics, watercolors clean easily with water.

For portraits, watercolor provides unique advantages:

-

Speed – Washes dry quickly, allowing an artist to capture a likeness in a single sitting.

-

Lightness – The transparency of pigments makes skin tones glow, ideal for lifelike portraits.

-

Flexibility – Watercolor can create both precise detail (for eyes, hair, and facial structure) and loose washes (for atmosphere and clothing).

-

Forgiveness through layering – Although difficult to erase, soft washes can be adjusted with lifting techniques, and glazing allows delicate corrections.

While the medium demands discipline—too much water can cause blooms, and overworking can dull colors—its immediacy makes it rewarding. Even beginners can capture a portrait’s essence, while masters achieve timeless beauty.

Seven Masterpieces in Watercolor Portraiture

1. Albrecht Dürer – Self-Portrait at Age Thirteen (1484, watercolor and silverpoint)

|

| Self-portrait at Thirteen Albrecht Dürer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The portrait reveals Dürer’s precocious skill. He used light washes to model the contours of the face, creating subtle shading around the eyes, nose, and lips.

The hair is carefully built with delicate strokes, while the background is left plain, focusing attention on the youthful features. The transparency of watercolor lends the portrait freshness, making it appear as though the boy’s gaze still lingers across centuries.

What makes this portrait remarkable is its immediacy. Rather than a stiff, formal representation, Dürer captured the softness of adolescence and his own emerging sense of identity. Watercolor’s lightness gave him a tool to suggest vulnerability and vitality simultaneously.

Today, this self-portrait is preserved in public collections and valued not only for its rarity but also for its testimony to the origins of one of history’s greatest artists. It shows that even in the late 15th century, watercolor could already serve as a profound medium for portraiture.

2. Hans Holbein the Younger – Portrait of Sir John Godsalve (c. 1532, watercolor on vellum)

|

| Sir John Godsalve Hans Holbein the Younger, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

His Portrait of Sir John Godsalve is a jewel-like example of how watercolor could achieve meticulous detail in likenesses.

The work is small but precise. Holbein used fine brushes and thin washes to capture the sitter’s facial features with extraordinary accuracy.

The delicate layering of pinks, reds, and ochres brings life to the skin tones, while tiny strokes define the hair and beard. Despite its size, the portrait conveys presence and dignity.

Watercolor’s role here is crucial: its translucency allowed Holbein to build subtle gradations without heaviness, which was essential for miniature formats. The technique created portraits that were portable, personal, and intimate—often exchanged as tokens of loyalty or affection.

Today, Holbein’s watercolor miniatures are housed in major collections and valued as both art and historical documentation. They capture not only likenesses but also the refinement of Renaissance portraiture. The Portrait of Sir John Godsalve demonstrates how watercolor could embody elegance, precision, and intimacy centuries before it became widespread in larger formats.

3. Thomas Gainsborough – Portrait of Mrs. Mary Graham (1777, watercolor study)

Though better known for his oil portraits, Thomas Gainsborough frequently employed watercolor for preparatory studies and expressive sketches. One surviving watercolor portrait of Mrs. Mary Graham demonstrates his fluid touch and ability to capture character with economy of means.

In this portrait, Gainsborough used swift washes to establish the sitter’s form and features. The face glows with delicately applied tones, while the hair and clothing are suggested with looser brushwork. The transparency of watercolor lends the portrait an air of spontaneity, as though capturing a fleeting impression rather than a fixed pose.

What makes this work powerful is its immediacy. Unlike formal oils, which demanded long sittings, watercolor enabled Gainsborough to seize personality quickly. Mrs. Graham’s grace and refinement shine through in just a few brushstrokes, proving that portraiture need not rely on elaborate detail to achieve presence.

Now preserved in public collections, such watercolor portraits by Gainsborough are treasured for their intimacy. They reveal the artist’s private process and his ability to use watercolor not merely as preparation but as an expressive portrait medium in its own right.

4. John Singer Sargent – Portrait of Lady with Umbrella (c. 1900, watercolor on paper)

|

| Lady with Parasol 1900, watercolor John Singer Sargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Sargent’s mastery of watercolor is evident in the handling of skin tones. He employed light washes, layered with precision, to create a sense of volume and translucency.

A few bold strokes define the features, while the background and clothing dissolve into loose, suggestive washes. This contrast draws attention to the face, the heart of the portrait.

The spontaneity of watercolor suited Sargent’s temperament. Unlike oils, which required long sittings, watercolors allowed him to capture subjects outdoors, in natural light, and with remarkable speed. In this work, the immediacy of the brush conveys both elegance and vitality.

Now in public collections, Sargent’s watercolor portraits are highly valued for their freshness and brilliance. They reveal a different side of his genius—more relaxed, intimate, and experimental—proving that watercolor could serve as a medium of both sophistication and immediacy in portraiture.

5. Paul Cézanne – Portrait of a Peasant (c. 1890, watercolor)

Paul Cézanne, known for his role in bridging Impressionism and Cubism, explored watercolor extensively in his later years. His Portrait of a Peasant demonstrates how he used the medium to deconstruct and reconstruct human likeness.

The portrait is composed of loose, patchy washes in muted blues, greens, and ochres. Cézanne leaves much of the paper exposed, allowing light to become part of the composition. The sitter’s features are sketched with economy, yet the angular application of color suggests structure beneath the surface.

Unlike traditional portraits that aimed for likeness and finish, Cézanne’s watercolor portrait captures essence through form and color. The sitter’s presence emerges through the interplay of transparent layers rather than detailed modeling. This analytical approach, possible through watercolor’s translucency, influenced later modernists profoundly.

Preserved in major collections, Cézanne’s watercolor portraits are valued not only for their beauty but also for their role in reshaping art’s direction. They show how watercolor could move beyond prettiness into rigorous exploration, making it a medium of intellectual as well as aesthetic depth.

6. Egon Schiele – Self-Portrait with Raised Bare Shoulder (1912, watercolor and gouache)

Egon Schiele, the Austrian Expressionist, used watercolor and gouache to create raw, emotionally charged portraits. His Self-Portrait with Raised Bare Shoulder exemplifies how the medium could express psychological intensity.

The portrait shows Schiele with an angular, almost contorted pose, his gaunt features emphasized by stark washes of color. He applied watercolor in bold, uneven strokes, leaving areas of paper exposed, heightening the sense of fragility. The eyes stare with intensity, confronting the viewer directly.

Watercolor’s immediacy amplified Schiele’s style. Its quick drying time allowed him to capture emotion in bursts of energy, while its translucency revealed vulnerability beneath the surface. The addition of opaque gouache enhanced certain areas, creating sharp contrasts and reinforcing the psychological tension.

Today, Schiele’s watercolors are exhibited in major European museums and highly prized at auction. They are valued not just for their technical innovation but for their raw honesty. His self-portraits in watercolor prove that the medium, often associated with delicacy, could also convey angst, intensity, and existential power.

7. Charles Demuth – Self-Portrait (1907, watercolor on paper)

Charles Demuth, an American modernist, often worked in watercolor, and his Self-Portrait from 1907 is an intimate example. Unlike his later Precisionist works, this early portrait is softer and more introspective.

Demuth rendered his features with transparent washes of muted tones, creating a delicate balance of light and shadow. The eyes, carefully detailed, draw the viewer into the artist’s inner world. Around the face, looser strokes suggest hair and clothing, leaving parts of the paper untouched. The unfinished quality gives the portrait a sense of immediacy and honesty.

Watercolor enabled Demuth to explore vulnerability. Its transparency suited the introspective nature of self-portraiture, where the artist seeks not grandeur but truth. The portrait captures not only likeness but mood, a quiet self-reflection.

Now preserved in public collections, this work is valued for its intimacy and as an early marker of Demuth’s evolving style. It shows how watercolor could be both personal and profound, offering artists a means of self-exploration unlike any other medium.

The Value and Display of Watercolor Portraits

Watercolor portraits by masters like Dürer, Holbein, Gainsborough, Sargent, Cézanne, Schiele, and Demuth are treasured in museums worldwide. Their monetary value is immense, with some fetching millions at auction, but their cultural and historical value is greater still.

Museums display watercolors with particular care, as the pigments are sensitive to light. They are often shown under controlled lighting and rotated to prevent fading. This fragility adds to their allure: seeing a watercolor portrait in person is often a rare and privileged experience.

Collectors value watercolor portraits for their intimacy and immediacy. Unlike oils, which can feel monumental, watercolors often reveal the artist’s hand more directly—every stroke, every decision is visible. They capture moments of vulnerability and experimentation, making them deeply personal works of art.

How to Master Watercolor Portraiture

For those who aspire to paint portraits in watercolor, mastery involves both technical skill and sensitivity.

-

Control Water and Pigment – Understanding the balance of water and pigment is essential. Too much water causes uncontrolled blooms; too little makes strokes harsh.

-

Layer with Transparency – Build skin tones through glazing, layering thin washes to achieve depth without heaviness.

-

Preserve White Space – Let the paper serve as a source of light, especially for highlights in eyes and skin.

-

Use Timing Wisely – Apply washes wet-on-wet for softness and wet-on-dry for sharper details.

-

Observe Likeness and Character – A portrait is not only about appearance but about presence. Study how light defines expression.

-

Experiment with Freedom – Watercolor thrives on spontaneity. Allow accidental blooms or drips to become part of the work’s life.

-

Consistent Practice – Frequent sketching from life builds confidence and fluency with the medium.

Conclusion

Watercolor portraiture combines accessibility with profundity. Easy to begin yet challenging to master, it allows artists to capture the essence of human presence with luminous delicacy. From Dürer’s youthful self-portrait to Holbein’s miniatures, from Gainsborough’s graceful studies to Sargent’s luminous ladies, from Cézanne’s analytical peasants to Schiele’s tortured self-portraits and Demuth’s introspective gaze, watercolor has proven itself as a medium capable of intimacy, honesty, and innovation.

Valued in museums and collections worldwide, watercolor portraits are displayed with care and admired for their freshness, fragility, and humanity. For the aspiring artist, they offer both a technical challenge and an artistic joy—the joy of watching pigment, water, and paper combine to reveal the human face in all its depth.