Introduction: A Singular Voice in Modern Art

|

| Self -portrait Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

He worked during a period when European art was exploding with experimentation: Cubism fractured form, Expressionism turned emotion into structure, and Fauvism wielded color like a weapon.

Modigliani absorbed elements from these currents yet remained stubbornly and poetically himself. His portraits negotiate a remarkable balance between stylization and psychological presence. They are modern and archaic at once—timeless more than “of their time.”

Although his career was tragically brief—he died at just 35—Modigliani’s output changed the course of portraiture and the depiction of the human figure. Today his paintings hang in the world’s leading museums and fetch nine-figure sums in the marketplace. This essay explores the essence of his painting style, the era he belonged to, his preferred subjects and influences, close readings of at least seven significant paintings, where his works can be seen now, and the ways collectors and institutions value them.

The Era: Montparnasse Modernism and the School of Paris

Modigliani belongs to the early 20th-century avant-garde centered in Paris, often called the School of Paris. This loose constellation of artists—many of them expatriates—made neighborhoods like Montparnasse into laboratories for new visual languages. While Cubism (Picasso, Braque) deconstructed form into faceted planes, Modigliani turned in another direction.

He looked backward to Renaissance elegance and archaic sculpture while pushing forward toward an essentialized modern line. If Cubism is analytic, Modigliani is lyrical. If Expressionism shouts, Modigliani whispers.

Chronologically, he overlaps with late Impressionism’s aftermath, Post-Impressionism’s legacy, and the full flowering of modernism between 1906 and 1920. His circle included poets, dealers, and fellow painters—Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, Constantin Brancusi, Chaim Soutine, and his dealer and friend Léopold Zborowski. Modigliani’s paintings sit comfortably within modernism’s embrace yet remain resistant to categorization, a hallmark of singular genius.

Modigliani’s Painting Style: Elongation, Line, and the Living Mask

|

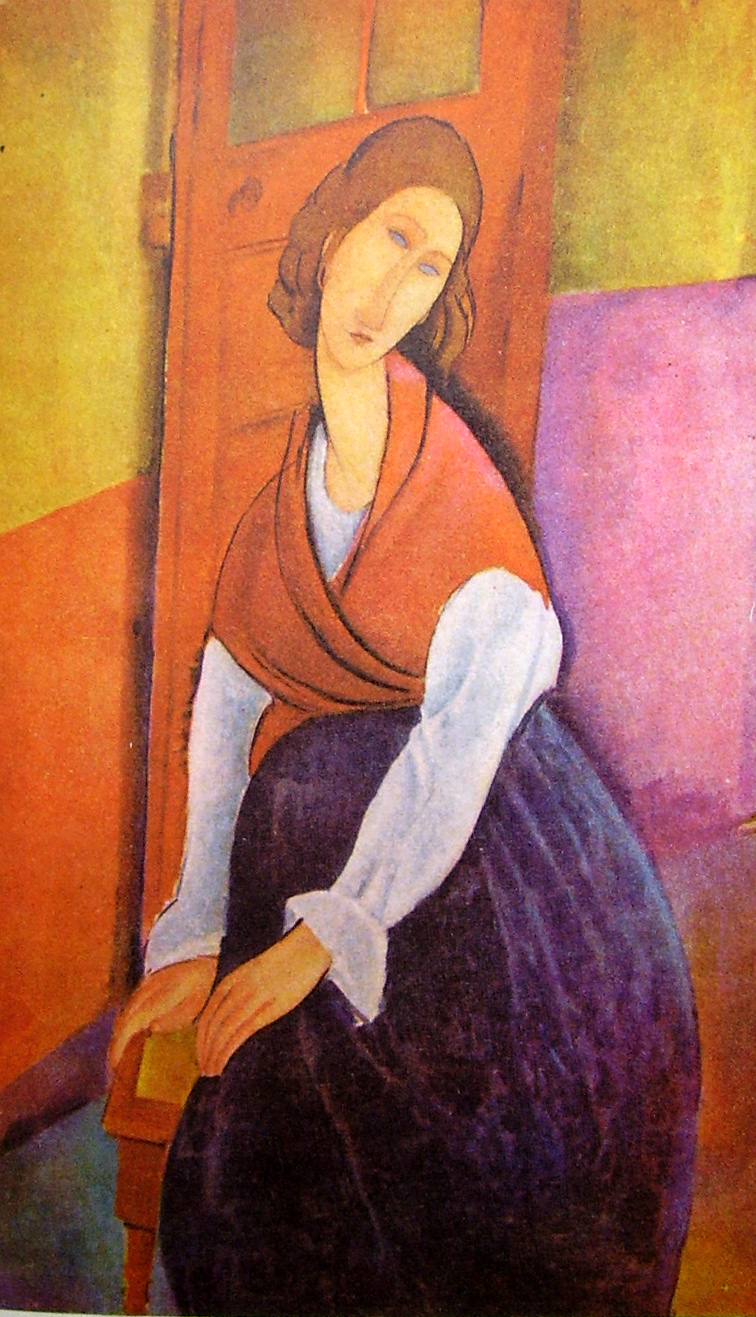

| Jeanne Hebuterne in Red Shawl Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

1) The Elongated Figure

Perhaps the most distinctive hallmark of Modigliani’s style is elongation—of necks, noses, faces, and sometimes torsos and limbs. These measured distortions are not accidents of observation but deliberate stylizations. They create a sense of grace and distance, elevating the sitter from everyday personality to archetype. Elongation stretches time itself; the figure feels classical and contemporary at once.

2) A Calligrapher’s Line

Modigliani drew with the confidence of a calligrapher. Even in oil, his contour lines can feel ink-like: descriptive, expressive, and economical. This linear authority came from years of obsessive drawing. He treated line as a musical staff—notes of curve and angle composing the sitter’s character. The line never fusses; it declares.

3) Almond Eyes and the “Unseeing” Gaze

Many Modigliani portraits bear his signature almond eyes, sometimes fully described, sometimes half-lidded, sometimes blank—left as pure fields of paint. These “unseeing” eyes are not empty; they suggest an interior life that is not on display. When he does paint the iris and pupil, the gaze comes through with blazing clarity. His choice—open or “closed”—acts like a switch between public and private, between likeness and symbol.

4) Sculptural Sensibility in Paint

From 1909 to roughly 1914, Modigliani produced a body of stone heads and caryatid studies (he dreamed of a temple of caryatids). Even after he returned predominantly to painting, sculpture never left his hand. The faces in his portraits feel carved; the long nose becomes a central ridge, the forehead a smooth plane, the mouth a chiseled incision. He builds forms with planar simplification and delicate, translucent passages, as if modeling stone with light.

5) Color as Atmosphere

His palette can be warm and earthy—ochres, siennas, rusts—punctuated by peacock blues, smoky greens, or ember reds. Color in Modigliani isn’t a Fauvist shout but a hum: it sets emotional temperature, unifies the composition, and supports the figure like a stage set supports an actor. Often backgrounds are thinly painted, scumbled, or patterned with the faintest of textures, keeping focus firmly on the sitter.

6) Oil Handling: Thin Veils and Matte Poise

He often applied paint thinly, letting ground layers breathe through and keeping surfaces matte rather than glossy. This lends an intimate, breath-close quality to the paintings. The figure emerges from a soft haze rather than a slick window, intensifying a sense of presence and vulnerability.

Choice of Subjects: The Human Being, Intensified

Portraiture

Modigliani was first and last a portraitist. He painted friends, fellow artists, lovers, patrons, and models. Each portrait is a negotiation between stylization and the sitter’s essence. The symmetries of the face, the architecture of the nose, the lift of the chin—he orchestrates these into a serene, iconic presence. Sitters include poets, dealers (such as Léopold Zborowski and Paul Guillaume), artists (like Chaïm Soutine), and the love of his life, Jeanne Hébuterne.

Children and Working-Class Sitters

Modigliani also painted children and anonymous models. In these works, stylization remains consistent, but the tone often softens. A child might be given a simple dress, a tilted head, and those familiar almond eyes, achieving poignancy without sentimentality.

Influences: Old Masters, Archaic Sculpture, and the Paris Avant-Garde

Italian Roots and Renaissance Poise

Born in Livorno, Modigliani grew up with Italian art in his bloodstream. Renaissance clarity and balance undergird his modernism. Look past the elongation and you find the poise of Botticelli and the serenity of classic Tuscan portraiture—translated into a new century’s idiom.

African, Cycladic, and Khmer Sculpture

Modigliani’s sculptural phase reveals deep study of African masks, Cycladic figures, and Khmer heads—sources widely discussed among Parisian artists then. From these he drew the long ovals, the narrow noses, the schematic mouths, and—crucially—the idea that simplification intensifies spirit.

Brancusi, Picasso, and the School of Paris

Friendships and rivalries mattered. Brancusi’s devotion to essential form and the search for “the essence of things” resonated with him. While Modigliani never turned Cubist, he borrowed Cubism’s lesson of structural economy, simplifying forms into graceful planes rather than facets.

Poetry, Illness, and a Short Life

Tuberculosis, poverty, and alcohol shadowed Modigliani’s life. Yet hardship never curdled the work. If anything, it sharpened his empathy. The faces he painted feel seen, honored, and mythologized—not in a grandiose way but with quiet dignity. He died in 1920; the next day, the pregnant Jeanne Hébuterne took her own life. Their brief, incandescent story has become part of the Modigliani mythos.

Six Paintings in Depth

Note: Modigliani produced many versions of certain subjects. The titles and dates below reference representative, widely recognized works that exemplify his language.

1) Jeanne Hébuterne (with Hat and Necklace), 1917

Modigliani painted Jeanne Hébuterne many times, charting a love story in paint. In this version, Jeanne sits with a large hat framing her face like a halo. The neck lengthens, the head tilts, and the eyes—those lids half-closed, those almonds half-sealed—pull us into meditation. The color scheme is restrained: velvety blacks, warm browns, a few luminous notes. Jeanne’s inwardness meets Modigliani’s stylization in a portrait that is affectionate but unsentimental.

The painting epitomizes his method: he draws structure with decisive contour, then floats thin layers of color inside the lines, never losing the integrity of the drawing. The result is a figure at once anchored and ethereal. It is impossible to separate the aesthetics from the biography here: Jeanne was his companion, muse, and, in the end, tragic echo. The portraits of her form a private altar within his oeuvre.

2) Portrait of Chaïm Soutine, 1916

|

| Portrait of Chaïm Soutine (1916) Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The background is a softly shifting field—neither flat nor distractingly detailed—setting off the figure like a relief. Soutine was a turbulent, expressive painter, yet Modigliani renders him with quiet steadiness, bordering on monumentality.

What’s striking is the calm confidence of the line. An eyebrow is a single sweep; a jawline a precise arc; the coat’s lapel, two angles meeting like origami. It would be easy for such stylization to flatten a person into a symbol.

Modigliani avoids that by calibrating the placements—the way the head leans, how the shoulders slope, the slight asymmetry of the ears. The result feels fiercely particular. You believe this is Soutine, and you see him as Modigliani saw him: an artist distilled.

3) Portrait of Léopold Zborowski, c. 1916–1919

|

| Portrait of Léopold Zborowski Amedeo Modigliani, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

The elongated nose and narrow face recall archaic heads, while the clothing is simplified into major shapes. The eyes—sometimes painted, sometimes left as luminous blanks—quiet the composition and lift the sitter into an emblem of patronage and friendship.

There is gratitude in this picture, but not flattery. Zborowski is shown as serious, gentle, and steady, the counterweight to Modigliani’s precarious life. The painting is also a roadmap of Modigliani’s formal concerns: flattened planes, elegant rhythms, tonal restraint, and the orchestration of figure against a subtly animated ground.

4) Lunia Czechowska, 1919

Lunia Czechowska, a close friend within Modigliani’s circle, occupies several portraits by the artist. In a 1919 version, she sits with hands clasped, her head inclined slightly, the long neck rising like a stem. The face is luminous, modeled with soft transitions; the eyes hover between inwardness and direct regard. Colors are tempered—smoky blues, autumnal browns, and a pearl skin tone—so that the drama is all in the drawing. The painting achieves quiet rapture.

Formal economy is key: Modigliani trims away anecdote and decoration, leaving only essentials—line, proportion, posture. Yet the sitter feels complete. The portrait’s power lies in its ability to suggest life beyond the frame while being composed like an icon. In Lunia’s case, you sense intelligence, reserve, and kindness, held inside the armature of Modigliani’s style.

5) Woman with a Fan (La Femme à l’éventail), 1919

|

| Woman with a Fan Amedeo Modigliani, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Modigliani’s background is delicately enlivened, not with pattern but with soft, atmospheric modulation. The face returns to his archetype: long oval, narrow nose, small mouth, eyes that may or may not be detailed depending on the version.

This painting is a lesson in restraint: everything is simplified to essentials, yet nothing feels empty. The fan acts like a hinge in the composition, balancing modesty and exposure, secrecy and display.

It is one of those pictures where you feel the artist’s breath in the stroke and the sitter’s breath in the quiet between strokes.

6) Gypsy Woman with Baby (La Bohémienne et l’enfant), 1919

Modigliani’s tenderness surfaces with special clarity in this composition of a young mother and child. The mother’s elongated neck and oval face bear his signature stylization, but the embrace is intimately observed. He balances the structural integrity of his line with softened modeling around the child’s head and the mother’s cheek—a subtle, humanizing warmth.

Color supports meaning: earthy reds and browns hold the figures in a common envelope; the background withdraws into a hushed, smoky atmosphere. The piece sits apart from the glamour of the poise of the dealer portraits. It presents ordinary love with extraordinary dignity. That democratizing spirit—granting archetypal gravity to an everyday subject—says much about Modigliani’s humanism.

Museums and Galleries: Where to See Modigliani Today

Modigliani’s paintings are dispersed across major museums and important private collections. While exhibitions periodically gather them together, you can encounter his works in many cities around the world. Institutions known to hold key paintings (or multiple works) include:

-

Paris: Musée de l’Orangerie (notable for portraits connected to Paul Guillaume); Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris; Centre Pompidou.

-

New York: The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

-

London: Tate; The Courtauld Gallery.

-

Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation (significant modern holdings that often include Modigliani).

-

Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art.

-

Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich (major modernist collections).

-

Jerusalem: The Israel Museum.

-

Basel: Kunstmuseum Basel.

-

Other notable venues: The Phillips Collection (Washington, D.C.), the Art Institute of Chicago, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), and museums across Italy (Livorno and Rome among them).

Because several iconic Modigliani portraits remain in private collections, museum labels and loan shows sometimes change which specific canvases are on public view at any given moment. Still, the institutions above provide a reliable map for seeing Modigliani’s art in person, and they frequently feature his work in permanent displays or special exhibitions.

How Modigliani’s Paintings Are Valued Because of:

1) The Power of a Singular Brand

Modigliani’s visual identity is among the strongest in 20th-century art. That unmistakable combination of elongation, mask-like faces, almond eyes, and warm, matte surfaces makes his paintings instantly recognizable. In the fine-art market, recognizability and a compelling mythology (the bohemian life, the tragic romance, the early death) amplify desirability, especially among collectors who seek masterpieces that “read” across a room.

2) Scarcity and Survival

His career was short, and the number of authenticated paintings is limited. Scarcity drives value. Modigliani’s early death froze his brand at the moment of peak artistic coherence; there is no “late decline,” no decades of uneven output to dilute the canon. Works in strong condition and with clear provenance sit at the top of the market.

4) Portraits and Key Sitters

Portraits of central figures in the Modigliani story—Jeanne Hébuterne, Zborowski, Soutine, and Paul Guillaume, among others—also command impressive prices, particularly when the paintings are of museum quality and in strong condition. A portrait with literary, art-historical, or dealer significance carries an added premium.

5) Authentication and Scholarship

Given the stakes, scholarship and authentication are crucial. Catalogue raisonnés, provenance research, and technical studies (pigments, ground layers, underdrawing) help verify attributions. Works with ironclad documentation, exhibition histories, and publication records both reassure buyers and elevate prices.

6) Museums vs. Private Collections

Some top-tier Modiglianis are effectively out of the market—enshrined in museum collections where they serve as cultural capital and attract visitors. Others circulate between private owners and occasionally appear at auction or on loan. A blockbuster sale can reset pricing expectations across the artist’s entire oeuvre.

7) Beyond the Sticker Price: Cultural Value

Any conversation about value that stops at money misses Modigliani’s deeper impact. His paintings taught the 20th century a new way to depict the human face—stylized yet soulful. Artists as different as Giacometti, Hockney, and contemporary figurative painters all work in the wake of Modigliani’s proposition: that simplification can reveal, not erase, the subject’s essence.

Why Modigliani Still Matters

Modigliani proposed that beauty is not a fixed set of proportions but a rhythm, a coherence of line and mass that touches our sense of the ideal. He allowed paint to breathe like stone and faces to function like masks—revealing by withholding. Decades after his death, audiences still respond to the dignity of his sitters, the calm of his compositions, and the hush that seems to settle around his canvases. In a century filled with fractured forms and conceptual gambits, Modigliani returned again and again to a single, inexhaustible subject: the human being—singular, mysterious, and worthy of a gaze that lasts.

Summary Checklist

-

Era: Early 20th-century modernism; School of Paris; Montparnasse avant-garde.

-

Style: Elongation; decisive contour; almond eyes (sometimes unpainted); sculptural modeling; warm, matte color; simplified planes.

-

Subjects: Portraits of friends, artists, dealers, lovers; occasional mother-and-child compositions and children.

-

Influences: Italian Renaissance balance; African/Cycladic/Khmer sculpture; Brancusi’s essence; Paris avant-garde dialogue.

-

Where to See: Major holdings in Paris (Orangerie, MAM Paris, Pompidou), New York (MoMA, Met, Guggenheim), London (Tate, Courtauld), Philadelphia (Barnes), Washington, D.C. (NGA), Zurich (Kunsthaus), Jerusalem (Israel Museum), Basel (Kunstmuseum), and others.

-

Valuation: Scarcity + myth + recognizability drive demand; some of his paintings have set record-level prices (well above $100M); portraits of key sitters are blue-chip; scholarship and provenance are decisive.

Conclusion: The Lasting Spell of Modigliani

Amedeo Modigliani distilled the portrait to its essentials and found, in those essentials, an inexhaustible well of humanity. He scraped away detail to reveal structure, simplified features to heighten presence, and treated every sitter—from lover to dealer to fellow painter—with an almost liturgical respect. His figures, serene and unsentimental, reclaim sensuality as form. His portraits choreograph line and plane into quiet icons of modern life.

He belongs to modernism yet seems to stand outside of time. Perhaps that is Modigliani’s greatest feat: he made modern art feel ancient and ancient art feel newly alive. Today, whether you encounter his canvases in Paris, New York, London, Jerusalem, Washington, Zurich, Basel, or Philadelphia—or in a catalog from a headline-making sale—you feel the same steady pull: the wish to sit longer, to look closer, to let the rhythm of that long neck and that calm oval face re-tune your breathing.

That steady pull is the measure of value that cannot be plotted on a graph: the slow astonishment his pictures produce. It is why museums guard his paintings like reliquaries and why collectors pursue them with unwavering zeal. In life, Modigliani searched—restlessly, brilliantly—for the ideal behind appearances. In death, his paintings continue the search on our behalf, asking us to meet the human face with reverence, and to see, within its simplified shapes, the complexity that makes us who we are.