Introduction

|

Georg Koberwein, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Queen Victoria (1819-1901) Royal Collection of the United Kingdom |

It encompassed sweeping political, industrial, and social changes that affected every aspect of life. While it was a time of economic expansion and the rise of the British Empire, it was also marked by intense social conservatism, especially regarding gender roles and family structures.

The image of the ideal Victorian woman—chaste, domestic, obedient, and self-sacrificing—was deeply embedded in cultural consciousness. Women were expected to find fulfillment within the confines of the home, their roles largely limited to those of wife, mother, or daughter.

The doctrine of separate spheres relegated women to the private realm, while men dominated the public sphere. Education for women was minimal, and employment opportunities were severely limited. Those who challenged this status quo were often ostracized or marginalized.

At the same time, the Victorian era was also a period of growing unrest with these rigid structures. The early feminist movement began to stir, challenging the limitations imposed on women’s lives. Prominent figures such as Mary Wollstonecraft, John Stuart Mill, and later suffragists like Millicent Fawcett began advocating for women’s rights, including access to education, employment, and political representation. These ideological shifts found a visual echo in the art of the time. Painters, both male and female, began to experiment with representations of women that moved beyond the traditional roles of angelic muses or decorative subjects. Instead, they painted women in moments of moral conflict, intellectual pursuit, emotional independence, and social resistance.

|

George W. Joy, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons The Bayswater Omnibus Museum of London |

The visual arts, especially when infused with literary and allegorical elements, became a mirror to the tensions between the entrenched patriarchal order and the burgeoning feminist consciousness.

While many artworks continued to perpetuate traditional ideals of femininity, a significant number subtly questioned the morality, double standards, and cultural expectations that governed women’s lives. Even when women were depicted in positions of weakness or vulnerability, the emotional and psychological depth given to them revealed a growing sensitivity to their inner struggles.

Importantly, it was not just female artists who contributed to this evolving discourse. Male artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and beyond also began to explore the complexity of female identity. Figures like William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted women with emotional nuance, often placing them in situations that questioned societal norms. Meanwhile, female artists like Emily Mary Osborn, Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler), and Rebecca Solomon used their canvases to highlight the lived realities of women—their struggles for economic independence, their professional aspirations, and the loneliness and stigma often associated with their roles.

What distinguishes the feminist undertones in these artworks is not always an overt call to arms but rather a quiet rebellion—a gaze that refuses to be submissive, a setting that reveals isolation, a gesture that hints at defiance. These artists painted women who were nameless and friendless, burdened by moral dilemmas, confined by class structures, or breaking free in acts of personal courage. In doing so, they anticipated the broader feminist movements that would follow in the 20th century.

This essay examines seven carefully chosen paintings from the Victorian era, each contributing to the feminist dialogue in its unique way. Through a detailed analysis of works by both male and female artists, the essay uncovers the layered symbolism and emotional narratives that challenge the dominant gender ideologies of the time.

These artworks not only illuminate the lived experiences of Victorian women but also reflect the artists’ evolving awareness of gender inequality. In depicting women not merely as ornamental or tragic, but as thinking, feeling, struggling beings, these paintings serve as important visual documents in the history of feminist thought.

The seven paintings analyzed in this essay—"The Awakening Conscience" by William Holman Hunt, "The Lady of Shalott" by John William Waterhouse, "Found" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, "Nameless and Friendless" by Emily Mary Osborn, "The Governess" by Rebecca Solomon, "The Roll Call" by Elizabeth Thompson, and "Claudio and Isabella" by William Holman Hunt—each articulate a different facet of the female condition in Victorian society.

Some reflect internal awakenings and moments of epiphany, others explore public humiliation and isolation, while still others celebrate female strength and competence in male-dominated arenas.

These works do more than present women in new lights—they raise questions. What does it mean for a woman to awaken to her moral and intellectual agency in a society that denies her both? How does a woman navigate the treacherous terrain of economic survival in a world that is structurally hostile to her ambitions? What happens when a woman dares to defy the societal mirror and confront the world directly, even at the cost of her life?

Through the examination of these visual narratives, we gain insight into the evolving feminist consciousness of the Victorian age—a consciousness that was still nascent, often hesitant, but undeniably present.

By weaving together art criticism, feminist theory, and historical context, this essay aims to reposition these Victorian paintings as more than relics of aesthetic tradition. They are, in many respects, acts of resistance—coded, symbolic, emotional resistance against a social order that sought to render women invisible or one-dimensional.

In bringing these narratives to the forefront, we not only honor the artists who dared to challenge norms but also the countless women whose lives, though seldom recorded in history books, found expression in the strokes of a paintbrush.

In the sections that follow, each painting will be examined with careful attention to visual elements, symbolism, historical background, and feminist interpretation. Together, they form a mosaic of Victorian womanhood—conflicted, confined, but never entirely silenced.

1. "The Awakening Conscience" by William Holman Hunt (1853)

|

William Holman Hunt, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Awakening Conscience |

The painting shows a young woman rising from the lap of her lover, her gaze turned toward the sunlight streaming through the window. Her expression is one of sudden realization or epiphany.

In Victorian society, a 'fallen woman'—usually one who engaged in sexual relationships outside marriage—was condemned.

However, Hunt’s painting invites sympathy for the woman. Rather than portraying her as corrupt, Hunt captures her moment of moral awakening. Her upward glance suggests a spiritual rebirth, and the discarded gloves and music books around her signify a life of triviality and entrapment.

Feminist interpretation sees this moment as an assertion of agency. The woman is not passive; she is reclaiming her consciousness, challenging the objectification and power dynamics in her relationship. Hunt, a Pre-Raphaelite, infused the work with symbolic detail that elevates the woman’s inner life, thus acknowledging her autonomy in a time when women were expected to be obedient and silent.

2. "The Lady of Shalott" by John William Waterhouse (1888)

|

John William Waterhouse, Public domain, via Wikimedia Common Tate Britain The Lady of Shalott |

She is seen floating down the river toward Camelot, surrounded by the symbolic objects of her confined existence.

The painting addresses the theme of female confinement and the struggle for self-expression.

Victorian women, especially those of the middle and upper classes, were often restricted to the domestic sphere, denied the freedom to participate in public life or express their desires.

Waterhouse’s Lady of Shalott, in choosing to look beyond her mirror, embodies a feminist yearning for knowledge and autonomy. Her journey toward Camelot, even at the cost of death, symbolizes a rebellion against a life of passive observation. The sorrowful yet determined expression on her face, the loosened ropes, and the extinguished lamp emphasize her defiance and sacrifice.

Feminist readings of the painting highlight the heroine’s courage in resisting the boundaries imposed upon her. Rather than glorifying her victimhood, Waterhouse’s portrayal evokes empathy and admiration for her choice to live, however briefly, on her own terms.

3. "Found" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1854–1881)

|

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Found Delaware Art Museum |

She collapses in shame and despair, draped in white, while a calf in a cart symbolizes her lost innocence and entrapment.

Though painted by a male artist, "Found" critiques the societal treatment of women who have transgressed sexual norms.

The woman is not vilified, but shown in a state of psychological torment. Her former lover's gaze is one of sadness rather than judgment, and his rural attire contrasts with her city-dwelling decline.

Rossetti’s handling of the theme is imbued with compassion. The painting challenges the Victorian dichotomy of the 'angel in the house' versus the 'fallen woman'. Feminist critics appreciate Rossetti’s attempt to humanize the woman, presenting her suffering as a social failure rather than a personal one. His use of natural symbolism, such as the tethered calf, critiques the commodification of female virtue.

4. "Nameless and Friendless" by Emily Mary Osborn (1857)

|

Emily Mary Osborn, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Nameless and Friendless Tate Britain |

Her attire and timid posture reveal her desperation, while the leering male gaze from the background emphasizes her vulnerability.

The painting powerfully critiques the limitations placed upon women in the art world and society at large.

The title underscores the isolation many women faced when attempting to navigate public spaces without male protection or patronage.

Feminist interpretation sees the painting as an assertion of female resilience. Despite the oppressive atmosphere, the woman maintains her dignity. Osborn herself was an advocate for women's rights and used her art to illuminate the structural inequalities women endured. Her choice to show a woman artist struggling in a patriarchal system anticipates later feminist critiques of gendered exclusion in the arts.

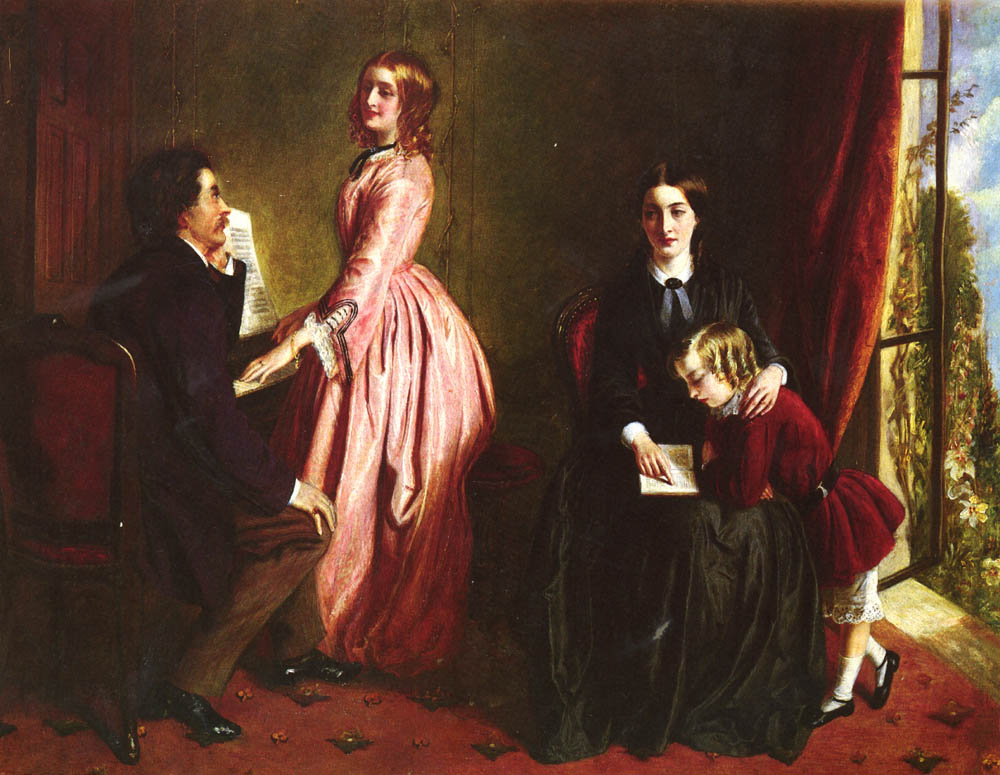

5. "The Governess" by Rebecca Solomon (1854)

|

Rebecca Solomon, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons The Governess |

The painting shows a governess—an educated but socially inferior woman—seated apart from the wealthy family she serves.

Her isolated position within the domestic interior visually emphasizes her marginal status.

The painting explores the constrained roles available to middle-class women. The governess was both an insider and outsider—trusted to educate children but excluded from family life and upward mobility. Her emotional detachment contrasts with the lively interaction between the children and their mother, highlighting her loneliness.

Feminist readings appreciate Solomon's nuanced depiction of class and gender intersections. The governess becomes a symbol of educated women relegated to servitude due to societal restrictions. The restrained color palette and tight composition enhance the sense of confinement, aligning with broader feminist concerns about women's lack of autonomy.

6. "The Roll Call" by Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) (1874)

Elizabeth Thompson's "The Roll Call" broke gender norms not only in its subject matter but also in its impact. The painting shows weary British soldiers after battle, lined up for a roll call. Although not explicitly feminist in content, the painting’s success marked a significant feminist milestone: a woman artist being publicly acknowledged for her mastery in a male-dominated genre—military painting.

Elizabeth Thompson, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons The Roll Call Royal Collection of the United Kingdom |

Thompson's achievement undermined Victorian notions that women could not tackle serious or historical subjects. Her technical brilliance, attention to realism, and emotional gravitas won critical acclaim. Queen Victoria herself praised the painting, and Thompson almost became the first female member of the Royal Academy.

Feminist perspectives celebrate "The Roll Call" as a breakthrough. By mastering the language of power—military heroism—Thompson carved space for women in institutional art circles. Her career paved the way for future generations of female artists who demanded equal recognition and representation.

7. "Claudio and Isabella" by William Holman Hunt (1850)

|

William Holman Hunt, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons Claudio and Isabella National Gallery, London |

Isabella is shown in emotional turmoil, torn between moral conviction and familial love.

Victorian morality often placed a premium on female purity, demanding sacrifice and silence. Hunt’s painting dramatizes this impossible dilemma, making visible the emotional cost of patriarchal virtue.

Isabella is not merely a figure of virtue; she is a woman grappling with real ethical stakes.

The composition emphasizes her centrality and spiritual strength, with light bathing her form. Claudio, in contrast, appears passive and resigned.

Feminist interpretations highlight the painting’s emphasis on female moral authority. It challenges the idea that women are merely virtuous ornaments, presenting Isabella as a moral agent, capable of complex thought and ethical reasoning.

Conclusion

Victorian painting, though born in a deeply patriarchal society, often carried undercurrents of feminist thought. Artists—both men and women—used the medium to interrogate gender roles, depict women's inner lives, and critique the social structures that limited female agency. From Hunt’s moral introspections to Waterhouse’s tragic heroines, from Osborn’s professional struggles to Solomon’s class critique, these paintings offer a multi-faceted view of the female experience.

Feminist art history invites us to re-evaluate these works not just as aesthetic achievements, but as political texts. They reveal the subtle yet profound ways Victorian artists grappled with the gendered expectations of their time, often planting the seeds of the feminist art movement that would bloom in the 20th century. Through their canvases, these painters gave voice to women's silenced narratives, creating a visual legacy that continues to inspire feminist discourse today.

Some of the important words used in this composition: Feminist Victorian paintings, feminist art history, women in Victorian art, William Holman Hunt, Emily Mary Osborn, Rebecca Solomon, Lady Butler, John William Waterhouse, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, feminist symbolism in painting, gender roles in Victorian art, Pre-Raphaelite feminist art, women artists of the 19th century, feminist analysis of Victorian era art.