The year was 1556, a pivotal moment in the annals of Indian history.

The air in Agra, the burgeoning capital of the nascent Mughal Empire, was thick with the scent of dust and anticipation.

Situated majestically on the banks of the sacred Yamuna River, Agra was a city poised on the cusp of a new artistic dawn. It was a time of consolidation for the new dynasty, with Emperor Humayun, recently restored to his throne after a period of exile, envisioning a cultural renaissance that would mirror the grandeur of his Persian heritage.

Into this vibrant tapestry of ambition and tradition, two figures of immense artistic stature were making their way through the city gates. They were not merely travelers; they were carriers of a profound artistic legacy, bringing with them the celebrated past of Persian art and the nascent future of Indian miniature painting.

These gentlemen, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad, hailed from the distant, culturally rich lands of Persia, present-day Iran. Their journey was no ordinary pilgrimage but a response to a heartfelt invitation from Emperor Humayun himself. Their arrival marked the beginning of a transformative chapter in Indian art history, a fusion of two distinct aesthetic sensibilities that would give birth to one of the most exquisite forms of painting the world has ever seen.

The Artistic Lineage: Persia's Finest Arrive

Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad were not just artists; they were luminaries of the Safavid school of painting, a tradition renowned for its intricate detailing, vibrant colours, and sophisticated narrative compositions. Mir Sayyid Ali, known for his masterful depictions of everyday life and his profound understanding of human emotion, was a student of the legendary Behzad, often considered the Raphael of the East.

Abdus Samad, on the other hand, was celebrated for his meticulous draftsmanship and his ability to render complex scenes with astonishing precision. Both had honed their skills in the royal ateliers of Tabriz, under the patronage of Shah Tahmasp I, where Persian miniature painting had reached its zenith.

Humayun’s encounter with these masters occurred during his enforced exile in the Safavid court. Having lost his empire to Sher Shah Suri, Humayun found refuge and intellectual solace in Persia. It was there, amidst the splendor of Persian art and culture, that he recognized the immense potential of this artistic style to serve as a visual chronicle of his own burgeoning empire.

He was captivated by the miniature's ability to capture grand narratives and intimate moments on a small scale, making it ideal for illustrating manuscripts and documenting court life. His invitation to Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad was thus not merely an act of patronage but a strategic move to import a sophisticated artistic tradition that would lend prestige and visual identity to his rule. Their arduous journey across mountains and deserts was a testament to their dedication to their craft and their faith in Humayun’s vision.

A New Bird in the Indian Flora and Fauna

It is crucial to understand that painting was by no means an alien concept in India. The subcontinent boasted a rich and ancient artistic heritage that predated the Mughals by millennia. The breathtaking wall paintings of Ajanta, Bagh, and Ellora, dating back to ancient and medieval times, stand as monumental testaments to India's profound contribution to the field of art.

These murals, vast in scale and epic in their depiction of Buddhist and Hindu narratives, demonstrated a mastery of colour, form, and spiritual expression. Furthermore, indigenous traditions of manuscript illumination, such as the Pala school in Eastern India and the Jain manuscript paintings in Western India, had flourished for centuries, albeit on palm leaves and paper, featuring stylized figures and vibrant, often flat, compositions.

However, the miniature painting that Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad brought was indeed a "new bird" in the artistic "flora and fauna" of the lands of the Ganga and Yamuna rivers. Unlike the grand murals that adorned cave walls or the relatively static figures of earlier manuscripts, Persian miniature offered a different aesthetic and technical approach.

It emphasized fine brushwork, delicate shading, a sophisticated sense of perspective (even if not strictly linear), and a narrative fluidity that allowed for complex storytelling within a small format. The Persian style also brought with it a distinct iconography, a refined palette, and a particular emphasis on courtly elegance and poetic allegory. This was not merely an evolution but a distinct introduction, a fresh artistic idiom ready to be absorbed and transformed by the fertile ground of Indian creativity.

The Genesis of a Style: Training and Transformation

Upon their arrival, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad were accorded immense respect and provided with the resources necessary to establish a royal atelier, or karkhana. Emperor Humayun, and later his son, the visionary Emperor Akbar, understood that the true strength of this new art form would lie not just in importing foreign talent but in nurturing indigenous talent. Thus began the crucial phase of training Indian artists.

The Persian masters embarked on a rigorous program, imparting the nuances of their craft to a generation of eager Indian painters. This was a true cross-cultural exchange. Indian artists, already skilled in their own traditions, learned new techniques: the preparation of pigments from minerals and vegetables, the meticulous grinding of lapis lazuli for blues and malachite for greens, the use of squirrel-hair brushes for incredibly fine lines, and the delicate application of gold and silver leaf.

They were taught Persian compositional principles, the art of rendering drapery with subtle folds, the depiction of idealized human forms, and the intricate patterns of carpets and architectural elements. The initial projects, such as the monumental Hamzanama (Adventures of Amir Hamza), a series of 1400 large paintings on cloth, served as a grand training ground, requiring hundreds of artists to collaborate under the guidance of the Persian masters. This massive undertaking, initiated by Humayun and largely completed under Akbar, was a crucible where Persian and Indian artistic sensibilities began to meld.

The Indianization of a Persian Art Form

As time passed, measured by the meticulous strokes of squirrel brushes on small canvases (typically paper, sometimes vellum), and by the shimmering application of gold and silver colours, the Persian flavour of the miniature began to subtly yet profoundly transform.

The initial adherence to Persian models gradually gave way to a unique synthesis, a testament to the adaptive genius of Indian artists and the inclusive vision of the Mughal emperors. Mughal Miniature Paintings, while retaining a refined Persian elegance, technically remained Indian in most of their characteristics.

The most striking aspect of this Indianization was the infusion of local elements into the subject matter. While Persian miniatures often depicted idealized landscapes and figures, Mughal miniatures increasingly drew inspiration from the vibrant reality of the Indian subcontinent.

The animal paintings were local, featuring the majestic elephants, tigers, and deer of India. The birds were from the Indian gardens, their plumage rendered with astonishing accuracy. The emperors and kings portrayed, though often depicted with a regal bearing influenced by Persian portraiture, were undeniably Indian in their features and cultural context.

The colour palette, initially dominated by the bright, jewel-like hues of Persia, began to incorporate the softer, more earthy tones characteristic of Indian art. Artists experimented tirelessly, trying to find newer shades from locally available materials, extracting pigments from indigenous plants, minerals, and even insects. This led to a richer, more nuanced spectrum of colours that reflected the diverse landscapes and vibrant culture of India.

Furthermore, the linear and somewhat flattened perspective of Persian painting gradually evolved. While never fully adopting the single-point perspective of European art, Mughal miniatures developed a more naturalistic approach to depicting space and depth. Landscapes became more expansive, featuring Indian flora like mango trees and banyan trees, and architectural elements were rendered with greater three-dimensionality.

The human figures, while still idealized, began to exhibit more distinct Indian physiognomy, with softer lines and a greater emphasis on individual expressions. The drapery of garments, too, moved away from purely Persian styles to reflect Indian attire.

The Golden Age Under Akbar and Rajput Kings

Under Emperor Akbar (1556-1605), the Mughal miniature painting truly blossomed. Akbar, a keen patron of the arts and a man of immense curiosity, established a large karkhana with over a hundred artists, many of whom were Hindu. He encouraged experimentation and a departure from strict Persian conventions. The Hamzanama was followed by other monumental projects like the Akbarnama (the official chronicle of his reign) and the illustrated Razmnama (a Persian translation of the Mahabharata).

These works were not just beautiful; they served as historical documents, moral treatises, and visual narratives that legitimized and celebrated the Mughal Empire. The collaborative nature of the atelier meant that different artists specialized in different aspects—one for outlines, another for colouring, a third for portraiture, and a fourth for borders. This division of labour, combined with Akbar's personal interest and encouragement, led to an unprecedented output of high-quality miniatures.

The reign of Emperor Jahangir (1605-1627) marked the zenith of Mughal miniature painting in terms of naturalism and refinement. Jahangir, a connoisseur and a keen observer of nature, elevated the art form to new heights of realism. He preferred individual portraits, studies of birds, animals, and flowers, and scenes that captured the intimate moments of court life.

Artists like Ustad Mansur became renowned for their astonishingly accurate and sensitive depictions of the natural world. Jahangir's personal interest meant that individual artists gained greater recognition, and the emphasis shifted from large collaborative projects to more refined, individualistic works. The brushwork became even finer, the colours more subtle, and the psychological depth in portraits more pronounced.

Elegance and Decline Under Shah Jahan and Beyond

Shah Jahan (1628-1658), known for his architectural marvels like the Taj Mahal, continued the patronage of miniature painting, though with a shift in aesthetic. His era saw an emphasis on formal portraits, grand court scenes, and architectural subjects, often featuring intricate borders and lavish use of gold and silver. The style became more formalized, elegant, and decorative, reflecting the opulence of his reign. While technically superb, there was less innovation compared to Akbar's and Jahangir's periods, with a greater focus on perfecting established styles.

Miniature Paintings Supported The Rajput Kings

The decline of imperial patronage under Aurangzeb (1658-1707), who was less inclined towards the arts, led to the gradual dispersal of artists from the imperial ateliers. However, this dispersal was not the end of Indian miniature painting; rather, it led to its fascinating diversification.

The Miniature painting Artists migrated to regional courts—Rajput, Pahari, and Deccan—carrying with them the Mughal techniques and aesthetics. Here, these techniques were adapted and infused with local themes, religious narratives, and distinct regional styles, giving rise to vibrant and unique schools of miniature painting that continued to flourish for centuries. The Rajput schools, for instance, embraced themes from Hindu mythology and epic poems, while the Pahari schools developed a lyrical and romantic style.

A Lasting Legacy

The journey of Indian Miniature painting, from the arrival of two Persian masters in Agra in 1556 to its flourishing and subsequent diversification across the subcontinent, is a testament to the power of cultural exchange and artistic synthesis. Mir Sayyid Ali and Abdus Samad were indeed carrying not just their past fame but the very future of Indian miniature art. What began as an imported art form was meticulously nurtured, absorbed, and transformed by Indian sensibilities, resulting in a distinct and uniquely Indian artistic expression.

These small, exquisite paintings, rendered with squirrel brushes and vibrant pigments, are more than just beautiful artifacts. They are historical documents, visual narratives, and profound expressions of a rich cultural heritage. They tell tales of emperors and commoners, of battles and celebrations, of flora and fauna, and of the enduring human spirit. The art of Indian Miniature painting stands as a magnificent bridge between cultures, a vibrant testament to the fusion of Persian elegance and Indian soul, forever etched onto the tiny canvases that captured the grandeur of empires and the delicate beauty of life.

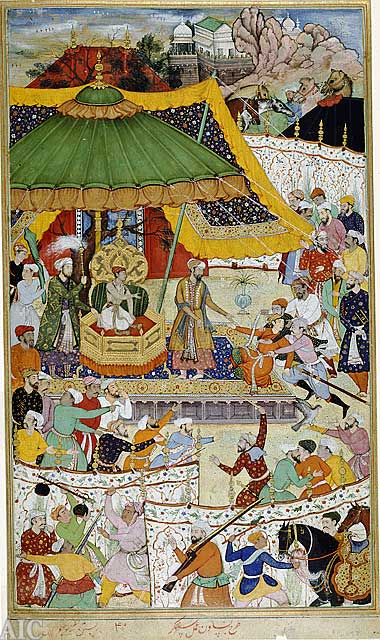

Now, let us decode one of the finest paintings done during the

time of Emperor Akbar. This painting depicts the scene wherein the Poet Abul

Fazl presents a copy of Akbarnama to Emperor Akbar. Akbarnama was a biography of Emperor Akbar, narrating his heroic deeds with miniature

illustrations. As it was customary to paint the miniatures on several levels,

this painting was also painted on three levels. Let us see what is narrated in

the upper half of the painting.

Obviously, the central figure is the

Emperor himself. Painted with a brighter yellow dress and red turban. No other

object is painted as bright red as his turban. Poet Abul Fazl, seated below the Emperor's seat, had a copy of the Akbarnama. The book was the result of

the skill and labour of several artists. It took at least two years to complete

the illustrations.

Here, the Emperor is not shown wearing a pompous dress as usual. But all other courtesans are well-dressed and standing silent, in respect-paying postures. On both sides of the Emperor, we see an equal number of courtesans, painted in almost identical attire with a similar technique.

|

Tailpiece The Secret Behind the Yellow Color in Indian Miniature Paintings

One of the most fascinating aspects of traditional Indian miniature paintings is the secret behind the vibrant yellow color used by ancient artists. Unlike modern synthetic pigments, the yellow hue in historical miniature art was created using a natural and eco-friendly method. Artists would feed mango leaves to specially cared-for cows. The urine of these cows, rich in natural pigments from the mango leaves, was then collected and carefully processed to extract the brilliant yellow color. This unique method reflects the deep connection between nature, tradition, and art in ancient Indian practices. The organic pigment was not only sustainable but also long-lasting, giving miniature paintings their timeless brilliance. This rare and ingenious technique showcases the extraordinary dedication of Indian miniature artists to achieve vibrant, natural colors—making it a captivating story for anyone interested in traditional Indian art, natural pigments, and historical painting techniques. |

The backside shows the articles used in the

emperor's court: the jugs and bowls, painted in subdued colours. The upper portion is the decorative balcony, painted in subdued red. The blue sky also marks its

presence.

What strikes our eyes most is the use of

yellow on the scarf the emperor had and the colour of the cloth on which he was

sitting. The gold must have been used to paint

this yellow. It is so bright. Look at the weist-skarf of every courtsan. All

are painted the same yellow.

If we see the overall effect of the

painting, we can arrive at the conclusion that the emperor wanted to declare that

he was a simple man. He did not believe in the royal and costly life. He wanted to

look like just another man in his surroundings.

|

| Emperor Akbar in his Court |

But the scene looks different. The Emperor, the courtesans and other attendees are in their festival attire. The place is not sitting on its regular premises; it is sitting in a tent-like arrangement.

The scene, in fact, looks like a make-shift court of justice. Look at the right-side middle portion. a person supposed to be a convict is tied with ropes. He must be a prisoner. he is presented before the emperor. so he must be a big head.

In ancient India and the medieval period, too, the kings and emperors were used to declare whether a person was a convict or not in such an open court.

What attracts our eyes is the levels of the painting. We can see five different parts in this painting, each part depicting a different scene. Though all the scenes are connected with the system of imparting justice and maintaining a law and order system.

|

Tailpiece How Mughal Decline Helped Spread Indian Miniature Painting to Rajput Courts

After the death of Emperor Shah Jahan, the rich patronage once enjoyed by miniature artists began to decline. His successor, Aurangzeb, showed little interest in supporting the arts, leading to a significant shift in the cultural landscape of India. Without imperial backing, many skilled miniature painters sought refuge and employment in the courts of regional Rajput rulers. This migration played a crucial role in the expansion of the Indian miniature painting tradition beyond the Mughal Empire. As these artists settled in remote areas under Rajput patronage, they infused their techniques with local styles, giving rise to unique regional schools such as Mewar, Marwar, Bundi, and Kota. This cultural movement not only preserved the art form but also enriched it with new themes, costumes, and narratives. The decentralization of patronage helped Indian miniature painting flourish across the subcontinent, making it a vital part of India’s diverse artistic heritage. |