|

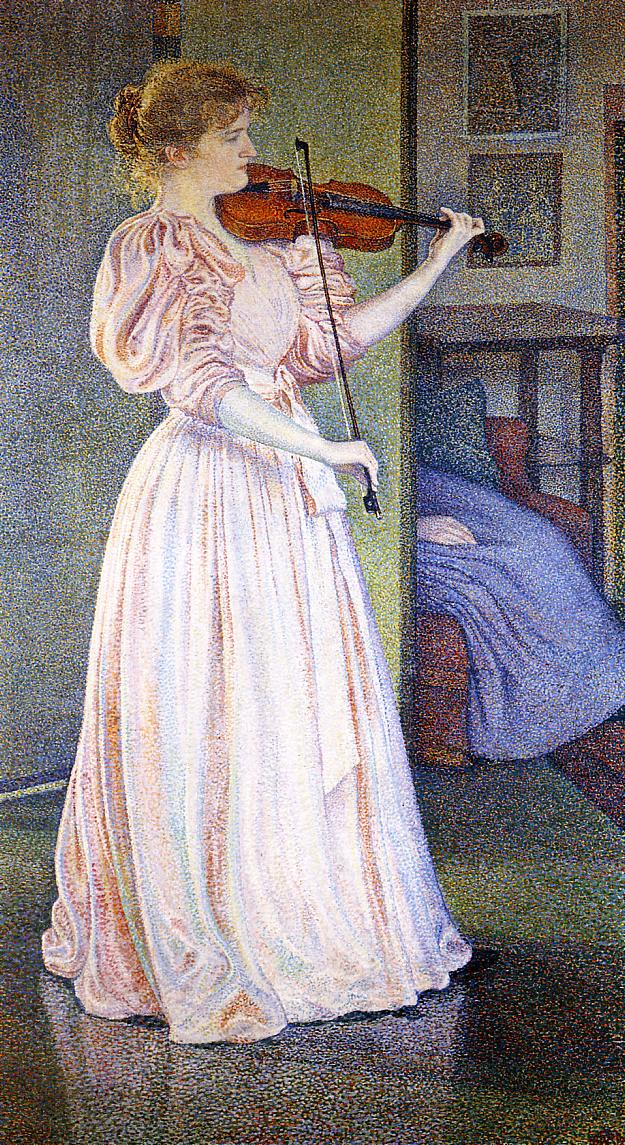

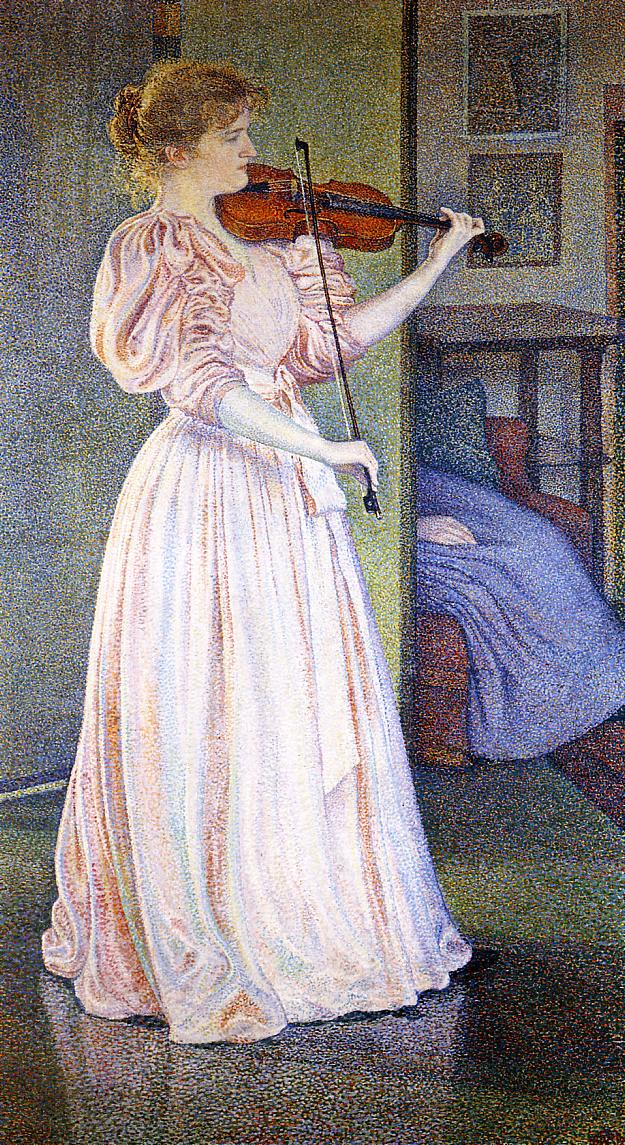

Yelkrokoyade, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Young Woman Powdering Herself Courtauld Institute of Art - University of London |

From the Romantic movement to the scientific revolutions of the era, the European consciousness was in flux. Amid this rapidly changing backdrop, the realm of visual art was also undergoing a profound transformation.

The lady represented here is the twenty-year-old Madeleine Knobloch, Seurat's lover. She later referred to this painting as "My Portrait", the artist himself chose the generic title it retains today

Artists began to challenge the representational conventions of the Renaissance, looking for new ways to interpret the world.

Within this ferment of experimentation and innovation emerged a young French artist whose brief life left a resounding impact on the history of painting—Georges Seurat (1859–1891). Through his creation of pointillism, he proposed not merely a new style, but a scientific method to art.

Origins of a Revolutionary Vision

Georges-Pierre Seurat was born in Paris in 1859. Trained at the École des Beaux-Arts, Seurat was grounded in academic traditions but simultaneously drawn toward contemporary theories of color and optics.

|

Science History Institute , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Creator : Chevreul, M. E. (Michel Eugène), 1786-1889; Digeon, René Henri |

While Impressionists captured fleeting moments and transient light effects using broken brushwork, Seurat developed a technique rooted in methodical precision.

Seurat’s intellectual curiosity was stimulated by the scientific color theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood, who explored the interaction of light and color.

These studies posited that colors placed adjacent to one another would visually blend in the viewer’s eye, rather than on the canvas.

Inspired by these theories, Seurat devised a style of painting that came to be known as pointillism—a technique that built entire images from tiny, individual dots of pure pigment.

What Is Pointillism in Art?

|

Yelkrokoyade, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Young Woman Powdering Herself Courtauld Institute of Art - University of London |

Pointillism is a revolutionary painting technique in which small, distinct dots of pure color are applied methodically to a canvas to create a larger, cohesive image. This artistic style, also known as divisionism, differs significantly from traditional painting methods where colors are mixed on a palette. In pointillism, colors are kept separate, and it is the viewer’s eye that blends them optically, creating a vibrant and luminous visual effect.

Each individual dot in a pointillist painting functions as both a standalone color element and a building block of the overall composition. When observed from a distance, these tiny points merge visually, offering the illusion of depth, shading, and dynamic movement. This creates a shimmering surface that appears to vibrate with energy and light.

The Role of Georges Seurat in Pointillism

Georges Seurat, a leading figure in the development of pointillism, elevated the technique into a scientific approach to color and composition. He envisioned his canvas as a visual laboratory where colors were not blended by the brush but by the viewer’s perception. His method of optical mixing encouraged the audience to engage actively with the artwork, making each viewing a collaborative experience between artist and observer.

While Impressionist artists focused on capturing fleeting moments and emotional impressions, Seurat brought a sense of structure, harmony, and balance to modern painting. His pointillist works, such as the iconic A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, demonstrate how calculated technique can result in both technical mastery and aesthetic beauty.

Why Pointillism Matters in Modern Art?

Pointillism paved the way for later developments in modern art and remains a topic of interest among art historians, students, and collectors. It bridges the gap between scientific theory and visual expression, making it a crucial movement in the evolution of Post-Impressionist art.

Whether you're exploring pointillism for an art project, learning its history, or simply admiring its visual magic, this technique stands out for its innovative use of color, viewer participation, and enduring influence in the art world.

The Science Behind the Dots

Seurat’s work was deeply influenced by Chevreul's law of simultaneous contrast, which suggested that two adjacent colors affect each other’s appearance. For instance, a blue dot next to a yellow one would enhance the perception of green, even though green paint was never applied. This principle allowed Seurat to build form and depth using pure color, rather than shading with black or grey.

He also used chromoluminarism—his own term for the effect of juxtaposing different hues to enhance their brilliance. His palette favored pure colors such as cobalt blue, French ultramarine, cadmium yellow, emerald green, and vermilion. He deliberately avoided muddy tones, trusting the eye to synthesize secondary hues through juxtaposition.

Seurat’s training in classical geometry helped him organize his compositions with an almost architectural rigor. His figures were carefully arranged in a balanced structure, often relying on vertical and horizontal axes. This geometry, combined with the vibrancy of pointillist technique, created a highly original form of painting—rooted in science, yet poetically evocative.

Seurat’s Key Paintings and Analysis

1. A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–86)

|

Georges Seurat, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Art Institute of Chicago |

Measuring nearly 7 by 10 feet, it took Seurat over two years to complete. In it, Parisians of all classes enjoy leisure time along the banks of the River Seine.

The scene is serene, yet deeply constructed—each figure poised as though on a theatrical stage.

The most striking aspect of this painting is its execution. Composed entirely of minuscule dots of pure color, the surface glows with a peculiar light. From a distance, the dots coalesce into forms with startling clarity and cohesion. Up close, the abstraction is apparent—an intricate tapestry of colors vibrating side by side. Seurat achieved a sense of stillness and timelessness, in contrast to the fleeting effects typical of Impressionism. The painting is now housed in the Art Institute of Chicago and is considered priceless, though if it were ever auctioned, it could command over $300 million based on market comparisons.

2. Bathers at Asnières (1884)

Completed before La Grande Jatte, Bathers at Asnières depicts a working-class suburb of Paris. The figures—male bathers lounging by the river—are rendered with monumental calmness. Though this work uses larger brushstrokes and fewer dots than his later pieces, it already hints at Seurat’s emerging divisionist technique.

The light, painted using pale hues and subtle contrasts, suggests a humid, lazy summer day. It’s a quiet meditation on leisure and class, and the compositional rigor reveals Seurat’s deep concern with harmony and balance. Today, it resides in the National Gallery, London, and though rarely discussed in mainstream circles, it is a cornerstone in the narrative arc of pointillism. A similar Seurat study or oil sketch might fetch between $10–30 million at auction, depending on provenance.

3. The Eiffel Tower (1889)

|

Georges Seurat, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Seurat’s interpretation of this new architectural wonder is notable for its reductionist elegance.

The canvas pulsates with chromatic energy. The sky, built from violet, white, and blue dots, suggests movement and light, while the Eiffel Tower itself rises with static force.

In this work, Seurat’s technique achieves a perfect synthesis between representation and abstraction.

It’s also a study in contrasts: between sky and steel, point and line, tradition and modernity.

The Eiffel Tower series is rare, and a known version held in private hands could easily surpass $50 million at a global auction.

4. The Circus (1890–91)

One of Seurat’s final works, The Circus remained unfinished at his death. The painting portrays a popular entertainment of the era, capturing the swirl of performers, horses, and audience with geometric clarity. The figures are arranged in careful symmetry, and the dots of primary and secondary colors—red, yellow, blue, orange—create a vibrating field of energy.

Despite the subject’s liveliness, the painting retains Seurat’s characteristic stillness. There’s a detachment that borders on the mathematical, as though the artist observed from a distance. The Circus is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris. If sold—which is highly improbable given its institutional importance—it would likely command a value between $200–250 million.

5. Lighthouse at Honfleur (1886)

|

Georges Seurat, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

Dots of green, blue, yellow, and white are placed with precision to evoke the glimmer of the sea and the softness of afternoon light.

The composition suggests tranquility, but its technique reveals deep complexity.

There’s no line that defines form; rather, the interplay of colors suggests volume, shadow, and distance.

This painting underscores Seurat’s genius in using minimal means to evoke maximum effect. It is a masterclass in visual harmony. Works of this scale and mastery in private hands are exceedingly rare and could reach upwards of $80 million in today’s art market.

Seurat's Influence and Legacy

Seurat’s technique influenced an entire generation of painters. Alongside artists like Paul Signac and Henri-Edmond Cross, the Neo-Impressionist movement gained ground. Though it never achieved the mainstream popularity of Impressionism, it laid crucial foundations for modernism, particularly in its emphasis on abstraction, color theory, and process. Artists as diverse as Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Robert Delaunay were impacted by Seurat’s formal innovations.

|

Georges Seurat, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Minneapolis Institute of Art Bridge and Hafen from Port-en-Bessin |

He did not depict what he felt, but what he calculated. This was not a lack of emotion, but rather a different kind of vision—one in which the laws of harmony, geometry, and perception became aesthetic tools.

The term "pointillism" was initially used derisively by critics, but it has since become a respected category of painting, and Seurat its unquestioned master. His commitment to scientific precision and his willingness to innovate gave painting a new dimension. He moved art from the subjective to the systematic—without losing its poetry.

The Contemporary Market and Valuation

Seurat’s paintings today are among the most highly valued artworks in the world. Because of his early death at the age of 31, his body of work is relatively small, making each canvas incredibly rare and precious. Most of his major works are housed in top-tier institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago, Musée d'Orsay, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The few works in private hands have achieved remarkable prices at auction. A small oil sketch related to La Grande Jatte sold at Sotheby’s for over $34 million. Experts estimate that a major Seurat canvas, if ever made available, could fetch between $150–300 million depending on condition, size, and provenance.

Additionally, studies, sketches, and drawings by Seurat—especially those related to pointillist projects—are also in high demand. A charcoal drawing can sell for over $2–5 million. His use of conte crayon, careful composition studies, and chromatic experiments are prized not only for their rarity but also for their glimpse into his meticulous working process.

Collectors value Seurat not merely for the rarity of his work but for his monumental contribution to the intellectualization of painting. He bridges the gap between the romantic painter and the scientific theorist.

Pointillism Artists Movement Era: A Revolutionary Dot in the Canvas of Art History, with Focus on Georges Seurat

The Pointillism artists’ movement, emerging in the late 19th century, marks a significant turning point in the evolution of modern art. Born as an offshoot of the Post-Impressionist movement, Pointillism introduced a new method of applying paint to canvas—using small, distinct dots of pure color that optically blend in the viewer’s eye. This meticulous yet groundbreaking technique challenged conventional brushwork and transformed the relationship between science, vision, and painting. At the heart of this movement stood Georges Seurat, a visionary artist whose intellectual approach to color theory and composition laid the foundation for Neo-Impressionism. This essay explores the origins, techniques, key artists, and enduring legacy of the Pointillism movement, with particular focus on the life and works of Georges Seurat.

Origins and Historical Context of Pointillism

The Pointillism movement, also referred to as Divisionism or Neo-Impressionism, originated in France in the mid-1880s. It was a reaction to the fluid brushstrokes and subjective perceptions of the Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. While Impressionists aimed to capture fleeting moments and the effects of light using spontaneous strokes, Pointillists sought a more scientific and structured approach to art. They believed that by understanding the optical and chemical properties of color, they could create artworks that were both aesthetically superior and intellectually profound.

This movement was closely linked to the burgeoning interest in color theory and optical science. Thinkers like Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood, and Charles Blanc had published works on how colors interact with one another and how the human eye perceives color contrasts. Their ideas significantly influenced Georges Seurat, who synthesized these scientific principles into a new form of visual expression.

Georges Seurat: The Architect of Pointillism

Georges Seurat (1859–1891) was the founding figure and most influential artist of the Pointillist movement. A classically trained painter with a strong interest in science, Seurat was determined to break away from traditional artistic norms. His early studies in optics, color harmony, and psychological responses to color helped him to formulate his own aesthetic approach.

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte Seurat’s magnum opus, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884–1886), is perhaps the most iconic example of Pointillism. This monumental painting, measuring over two by three meters, depicts Parisians leisurely strolling and relaxing along the Seine River. Instead of blending pigments on a palette or canvas, Seurat applied tiny dabs and dots of unmixed colors. The result is an astonishing optical fusion that occurs in the eye of the observer, creating luminous and vibrant imagery.

What makes this painting revolutionary is not just its technique but also its compositional precision. Seurat used mathematical structure, careful planning, and preliminary studies to arrange figures and landscapes in a harmonious yet non-spontaneous scene. Every element is deliberate—right down to the shadows cast on the grass. It took Seurat nearly two years to complete the work, which became a manifesto for the Pointillist movement.

Core Techniques of Pointillism

At its heart, Pointillism relies on a meticulous dot-by-dot application of pure, unmixed colors. The three fundamental principles of the technique include:

1. Optical Mixing

Rather than physically mixing pigments on the palette, Pointillist artists place small dots of complementary colors close together. When viewed from a distance, the eye blends these colors into new tones. For example, blue and yellow dots appear green when perceived from afar. This technique results in a more luminous and vibrant surface than traditional mixing.

2. Scientific Color Theory

Influenced by the studies of Chevreul and Rood, Pointillist painters were meticulous in their use of complementary colors, warm and cool contrasts, and simultaneous contrast. Seurat, in particular, followed scientific logic in color placement to generate emotional responses and spatial depth.

3. Rhythmic Composition and Order

Unlike Impressionists, Pointillists were obsessed with structure and design. Seurat and his followers would often perform extensive preparatory sketches and studies. They emphasized verticals, horizontals, and diagonals to control visual rhythm and balance.

Other Prominent Pointillist Artists

While Georges Seurat was the pioneer, other artists quickly joined and expanded the movement.

Paul Signac

A close associate of Seurat, Paul Signac (1863–1935) became a leading figure in Pointillism after Seurat’s untimely death in 1891. Signac developed the technique further and even published a theoretical treatise titled From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism. His works, such as The Port of Saint-Tropez, demonstrate a more colorful and fluid adaptation of the pointillist method. Signac also promoted the technique throughout Europe, influencing later modernists.

Henri-Edmond Cross

Cross brought a lyrical quality to Pointillism, with his use of vivid Mediterranean colors and more abstracted forms. His works like The Pink Cloud and The Evening Air introduced a sensuousness that foreshadowed Fauvism.

Camille Pissarro

Originally an Impressionist, Pissarro briefly experimented with Pointillism under Seurat’s influence. Though he eventually returned to a freer brushwork, his pointillist period yielded works like Apple Picking, which demonstrate a fascinating blend of Impressionist light and pointillist precision.

Critical Reception and Challenges

Initially, Pointillism was met with skepticism and ridicule. Critics referred to it mockingly as “dotty” painting, and many believed that its rigid method removed emotion and spontaneity from art. Even some of Seurat’s contemporaries found the style too controlled and scientific.

However, as the 20th century dawned, attitudes shifted. Art critics began to see Pointillism not as cold or mathematical, but as pioneering and visionary. It paved the way for modern abstraction and for movements that explored color theory and perception, such as Fauvism, Cubism, and Orphism.

Legacy and Influence of the Pointillism Movement

The influence of Pointillism stretches far beyond the late 19th century. Its insistence on optical effects and color interaction directly influenced the Fauvist painters like Henri Matisse, who admired its color intensity, even if they discarded its disciplined dotting technique. Likewise, Robert Delaunay and the Orphists drew on Pointillist ideas in their experiments with color and movement.

In the 20th century, Pointillism also found echoes in Op Art, with artists like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley exploring similar ideas of optical illusion and viewer perception. Even in the realm of digital art, Pointillism’s concept of building images pixel by pixel resonates strongly with modern techniques.

Moreover, contemporary artists and illustrators continue to experiment with stippling and dot-based art inspired by Seurat’s meticulous legacy. Modern digital tools often mimic pointillist techniques to generate textured, layered compositions.

The Science Behind the Dots

Portrait-of-irma-sethe-1894

Théo van Rysselberghe

Musee do petit Palais in Geneva

One of the most fascinating aspects of Pointillism is its embrace of scientific reasoning within an artistic framework. Georges Seurat approached painting like an engineer—analyzing visual problems and applying calculated solutions.

He was particularly intrigued by how colors interact and how the eye can blend adjacent hues to create luminosity.

Seurat’s method reflects a belief that art can be systematized, that beauty can be mathematically constructed through color equations.

While this approach may seem cold to some, it actually demonstrates a profound respect for the viewer’s perception. Seurat didn’t want to tell you what to see; he wanted your eye to construct the image itself.

This intersection of art and science gave Pointillism a unique place in the art world, distinguishing it from both the Impressionists before it and the Expressionists who followed.

Théo van Rysselberghe

Musee do petit Palais in Geneva

Conclusion: The Enduring Dot

The Pointillism artists’ movement was a radical reimagining of how we perceive color, form, and visual harmony. While the movement itself was relatively short-lived, its impact on the trajectory of modern art cannot be overstated. At the center of it all was Georges Seurat, whose devotion to order, logic, and visual sensation redefined painting in an era of artistic revolution.

From the serene geometry of La Grande Jatte to the luminous vistas of Signac and Cross, Pointillism remains a testament to how a simple dot—when multiplied with intent—can change the world of art. In the digital age, where images are built pixel by pixel, the spirit of Pointillism continues to thrive, reminding us that in the smallest points, vast visions can unfold.

Georges Seurat’s art is an exceptional blend of science and imagination. Through the invention of pointillism, he not only introduced a novel technique but changed the way we think about color, form, and perception. His style—precise, deliberate, luminous—has had an enduring impact on modern art. His dots were not merely marks on a canvas; they were a language, a method, and a philosophy.

In the hands of Seurat, a dot became more than a unit—it became a portal through which light, movement, and meaning could enter the world. Though his life was tragically brief, the radiance of his vision continues to shine through every dotted composition he left behind.

Seurat stands as a reminder that innovation often comes from those willing to combine tradition with theory, intuition with calculation, and discipline with daring. His legacy is not merely a technique called pointillism. It is an invitation to see the world—not in broad strokes, but in carefully placed, luminous details.

Some of the important words used in this composition: Pointillism artists movement, Georges Seurat, Neo-Impressionism, pointillist painting technique, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, Paul Signac, Henri-Edmond Cross, color theory in painting, Divisionism art, optical mixing, post-impressionist painters, scientific art methods, Seurat paintings, Pointillism legacy, 19th-century art movements.