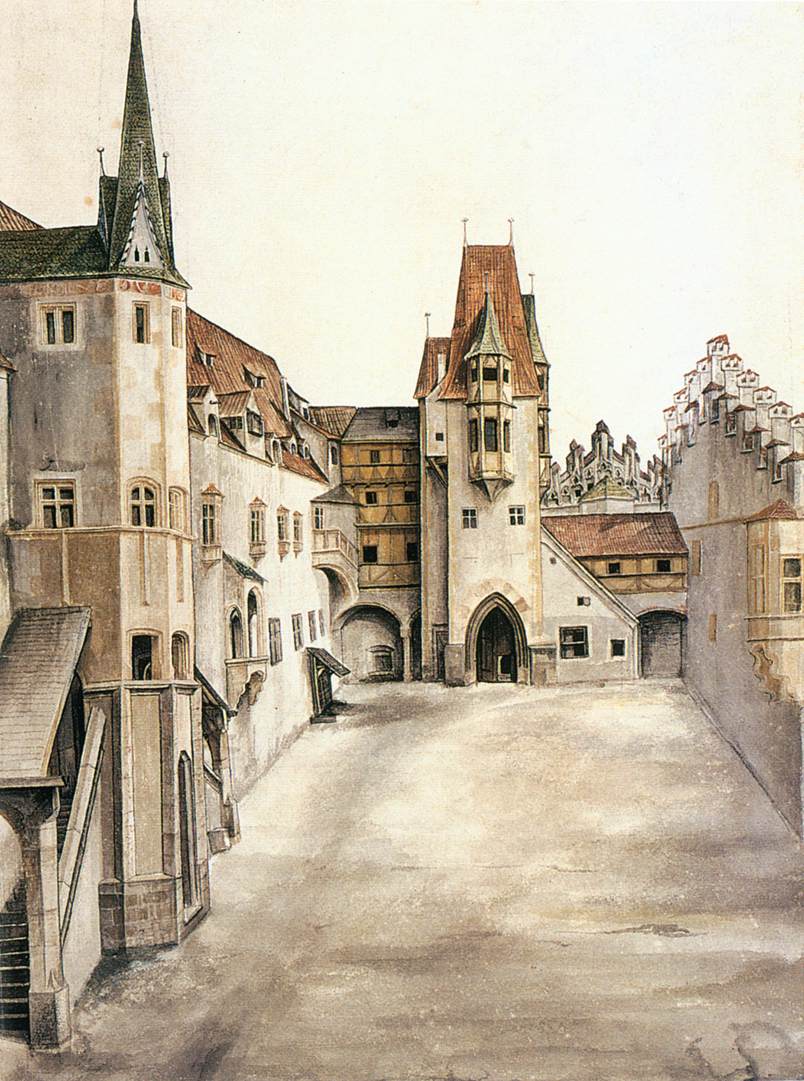

Courtyard of the Former Castle 1494

Albrecht Dürer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Introduction: The Essence of Watercolor

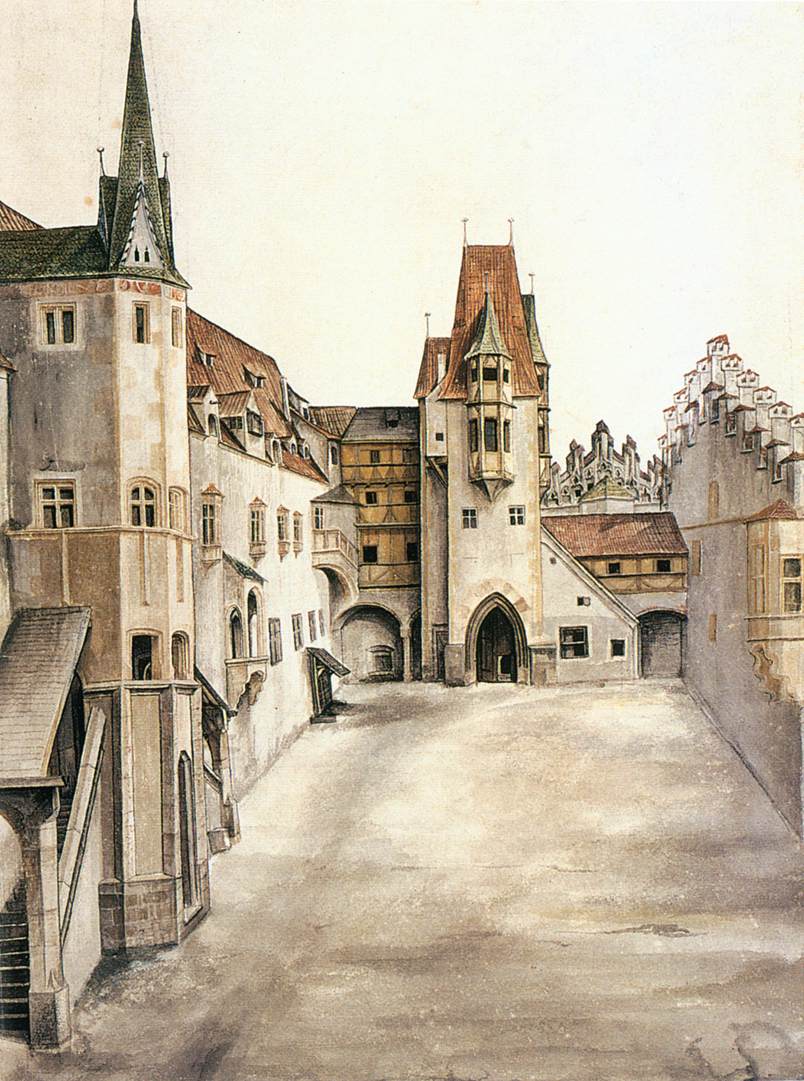

Albrecht Dürer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Watercolor painting, with its luminous washes and delicate layering, has long been celebrated as one of the most poetic forms of artistic expression.

Unlike oils and acrylics, which cloak the surface with pigments, watercolor relies on the transparency of thin washes, allowing light to pass through and reflect from the white surface beneath. This gives watercolor works a sense of brilliance and spontaneity unmatched by other media.

The roots of watercolor stretch back centuries. Early civilizations used natural pigments mixed with water to decorate manuscripts and create illustrations.

By the Renaissance, European masters were employing watercolor for botanical studies and landscape sketches. Later, during the 18th and 19th centuries, watercolor blossomed into a respected art form in its own right, with great artists creating masterpieces that combined immediacy with depth.

This essay will narrate the art of watercolor, describe seven notable public domain watercolor paintings by master artists, reflect on the easiness and challenges of the medium, explain how such paintings are valued and displayed, and provide guidance for aspiring painters to gain mastery.

Watercolor painting by John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

John Singer Sargent, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Qualities and Easiness of Watercolor

Watercolor is often regarded as a medium of simplicity, requiring little more than brushes, pigment, and paper. Yet its simplicity belies complexity. It is easy to begin—children experiment with watercolor in school—but difficult to truly master. The main reason is its transparency and fluidity. Every stroke shows; mistakes cannot always be covered. But this very quality also gives watercolor its freshness, immediacy, and lightness.

Watercolors dry quickly, enabling artists to work rapidly, capturing fleeting impressions of light and atmosphere. They are portable, making them ideal for travel sketching and plein air painting. They are also forgiving in their own way: with water and tissue, some corrections can be made, and the fluid washes encourage creative accidents that sometimes enrich the work.

This balance between control and spontaneity makes watercolor beloved by both amateurs and professionals. Its accessibility ensures that anyone can pick up a brush and begin, but the path to mastery requires understanding water control, timing, layering, and the balance of translucency and opacity.

Seven Masterpieces in Watercolor

1. Albrecht Dürer – Young Hare (1502)

|

| A Young Hare watercolor painting Albrecht Dürer, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Painted in 1502, it demonstrates the astonishing realism achievable with the medium, even in its early use.

The subject is a simple hare, portrayed sitting on bare ground, but the execution elevates it to a marvel of observation.

Dürer combined fine brushstrokes, layered washes, and delicate touches of opaque gouache to capture the animal’s fur, whiskers, and alert eyes.

Each strand of hair is rendered with precision, yet the softness of watercolor avoids rigidity, giving the hare a lifelike vibrancy. The subtle play of light across its fur, from warm browns to silvery highlights, shows Dürer’s mastery in blending washes and controlling transparency.

Though small in scale, the work conveys not only anatomical accuracy but also a sense of presence, as if the hare might spring into motion. It reflects Renaissance humanism—the celebration of nature as worthy of close study.

Now housed in the Albertina Museum in Vienna, Young Hare is a treasured public domain masterpiece. It shows that watercolor, even in its infancy as a serious medium, could achieve both scientific precision and artistic beauty.

2. J. M. W. Turner – The Blue Rigi, Sunrise (1842)

|

| The Blue Rigi, Sunrise Watercolor on paper J. M. W. Turner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Blue Rigi, Sunrise, painted in 1842, depicts the Swiss mountain Rigi bathed in dawn light, its slopes glowing softly above a tranquil lake.

The painting is composed almost entirely of delicate washes. Turner layered blues, purples, and warm yellows, using the translucency of watercolor to evoke atmosphere rather than detail.

The mountain dissolves into mist; the sky glows with subtle gradations of color. Sparse foreground elements—a boat and figures—anchor the composition, but the true subject is light itself.

Turner’s control of watercolor is astonishing. He allowed pigments to diffuse naturally with water, capturing the ethereal quality of dawn. Where necessary, he added sharper lines and opaque touches, balancing spontaneity with intentionality.

This work epitomizes the Romantic yearning for the sublime in nature, portraying not just a mountain but an emotional response to its majesty. Today, The Blue Rigi is revered as one of the finest watercolors ever made, housed in the Tate collection. Its value lies in its ability to capture an unrepeatable moment of light, reminding viewers of watercolor’s power to convey atmosphere beyond mere representation.

3. Winslow Homer – The Blue Boat (1892)

|

| The Blue Boat watercolor painting Winslow Homer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Blue Boat (1892) exemplifies his mature style. It shows two men rowing a boat across choppy waters, with distant hills faintly visible.

The painting demonstrates Homer’s mastery of watercolor’s dual qualities: looseness and precision.

Broad washes form the sky and water, while finer brushwork defines the figures and oars. The boat’s bright blue contrasts sharply with the surrounding grays and greens, anchoring the viewer’s focus.

Homer used the whiteness of the paper itself to represent light glinting on the waves. The transparent layers of pigment give depth to the water, suggesting both movement and danger. The figures are sturdy, painted with minimal strokes yet filled with strength and concentration.

This scene is more than a marine study—it is a metaphor for human endurance against nature’s forces. Homer often depicted ordinary people engaged in struggles that mirrored larger themes of survival and dignity.

The Blue Boat, preserved in public collections, remains one of the finest examples of American watercolor. It demonstrates how the medium, though delicate, can portray vigor, drama, and psychological depth.

4. John Singer Sargent – Venetian Canal (c. 1902)

John Singer Sargent, best known for his dazzling oil portraits, was also a prolific watercolorist. His Venetian Canal series captures the beauty of Venice with a freshness only watercolor can deliver. One particular view, painted around 1902, shows gondolas gliding through narrow waterways, with sunlit buildings rising above.

Sargent employed rapid, confident strokes, allowing the water to bleed into the pigment for reflections. His brushwork suggests detail without overdefining, letting the viewer’s eye complete the forms. The interplay of warm ochres, cool blues, and shimmering whites evokes both the architecture and the watery atmosphere of Venice.

What makes this work remarkable is its spontaneity. Unlike his formal portraits, Sargent’s watercolors were often painted outdoors, on the spot, with remarkable speed. He captured not only the scene but the sensation of being there—the flicker of light, the sparkle on ripples, the fleeting impression of movement.

Today, Sargent’s Venetian watercolors are displayed in major museums and prized for their brilliance. They show how watercolor can record impressions with immediacy and liveliness unmatched by other media. His mastery reminds us that watercolor can be bold and expressive, not merely delicate.

5. John Singer Sargent (c. 1902–1906)

Paul Cézanne, often called the father of modern art, used watercolor in experimental ways that anticipated abstraction. His series of watercolors depicting Mont Sainte-Victoire near Aix-en-Provence are among his finest achievements.

In one version from the early 1900s, Cézanne used pale washes of blue, green, and ochre to construct the mountain and landscape. The brushstrokes are loose, leaving areas of the white paper exposed. This interplay of painted and unpainted areas gives the work luminosity and openness.

Cézanne’s genius lies in using watercolor not just to depict but to analyze. Each stroke is like a building block, assembling form and space. The mountain becomes both a physical presence and an abstract structure of color planes. The viewer sees not only a landscape but the very process of perception.

This approach deeply influenced later artists, including the Cubists. Cézanne’s watercolors showed how the medium could be rigorous and intellectual, not merely decorative.

Today, such works reside in public museums and are valued not only for their beauty but for their historical role in reshaping modern art. They prove that watercolor can carry the weight of radical innovation.

6. William Blake – The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (c. 1805–1810)

William Blake, poet and visionary artist, used watercolor in profoundly imaginative ways. His series of Great Red Dragon paintings, created between 1805 and 1810, are among his most dramatic works, combining biblical imagery with personal myth-making.

In The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun, Blake depicts a monstrous winged figure looming over a radiant woman. Watercolor allowed him to create stark contrasts: the dragon’s dark, muscular form dominates the upper canvas, while delicate washes of gold and pale hues surround the woman below.

Blake used strong lines to define forms, but his washes provided atmosphere and drama. The transparency of watercolor enhanced the spiritual intensity, making the scene appear both real and otherworldly. Unlike naturalistic watercolorists, Blake used the medium symbolically, fusing words, visions, and images into one.

Today, this painting belongs to public collections and remains a cornerstone of Romantic and visionary art. Its value lies not only in Blake’s technical use of watercolor but in its imaginative force. It demonstrates that watercolor can express profound mythic and spiritual themes, transcending its reputation as a light, decorative medium.

7. John James Audubon – American Flamingo (1838)

|

| American Flamingo 1838 National Gallery of Art , CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Audubon’s mastery of watercolor allowed him to combine scientific accuracy with artistic elegance. He used transparent washes to build up the flamingo’s feathers, creating texture and depth without sacrificing vibrancy.

The balance of pinks and reds, offset by the white background and subtle landscape, makes the bird appear both lifelike and monumental.

What distinguishes Audubon’s work is scale and precision. Each bird in his series was depicted life-sized, requiring both technical skill and compositional ingenuity. In American Flamingo, the bird’s elegant pose accommodates its size within the page, while also revealing characteristic behavior.

Today, Audubon’s watercolors are preserved in institutions and treasured not only by art lovers but also by scientists and historians. Their value is immense, as they represent one of the greatest achievements in documenting wildlife through art. The American Flamingo shows how watercolor can unite science, beauty, and grandeur.

The Value and Display of Watercolor Paintings

Watercolor paintings, once considered less prestigious than oils, are now highly prized in the art world. Works by Turner, Homer, and Sargent are displayed in leading museums such as the Tate, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Albertina. Their market value can be extraordinary: masterpieces have sold for millions at auction.

Museums take special care in displaying watercolors, as the pigments are more sensitive to light than oils or acrylics. They are often shown under dim lighting and rotated to prevent fading. This fragility adds to their rarity and value, making each public viewing a special occasion.

Collectors and historians recognize that watercolors embody immediacy and intimacy. They are not only valued for technical brilliance but also for their insight into the artist’s mind—often revealing sketches, experiments, or spontaneous impressions that oils conceal.

How to Master Watercolor Painting

Mastery of watercolor is a lifelong journey. Some guiding principles include:

-

Understanding water control – Learn how much water to load on the brush, how to manage washes, and how to let pigments flow without losing control.

-

Layering (glazing) – Apply thin washes over dry layers to build depth and luminosity.

-

Timing – Knowing when to apply wet-on-wet for soft blending and when to use dry brush for crisp detail.

-

Using white space – Preserve the paper’s whiteness as a source of light, rather than covering everything.

-

Experimentation – Watercolor rewards exploration: granulation, splattering, lifting, and unconventional tools can create surprising effects.

-

Observation – Study nature, light, and shadow. Great watercolorists often excel at seeing and recording fleeting impressions.

While watercolor may seem daunting, its immediacy is also its gift. With practice, patience, and courage to embrace accidents, artists can develop fluency in this delicate yet powerful medium.

Conclusion

Watercolor painting is an art of light, transparency, and immediacy. From Dürer’s precise Young Hare to Turner’s ethereal Blue Rigi, from Homer’s rugged Blue Boat to Sargent’s vibrant Venetian scenes, from Cézanne’s analytical landscapes to Blake’s visionary imagery and Audubon’s monumental flamingos, the medium has demonstrated extraordinary range.

Though easy to begin, watercolor demands years to master. Its fragility makes it precious, its spontaneity makes it alive, and its intimacy makes it deeply personal. Today, watercolor masterpieces hang in the world’s greatest museums, valued both for their beauty and their role in art history.

For those who wish to master it, watercolor offers not only technical challenges but also profound joy—the joy of watching pigment and water dance together on paper, creating something luminous and unique.