The dawn of the 20th century was a crucible of transformation. Industrialization reshaped cities, scientific theories upended understanding, and the specter of world war shattered long-held ideals of progress and reason.

In this maelstrom of modernity, art could no longer be content with merely replicating the visible world. A new, urgent need arose: to express the inner world of emotion, the subjective experience of anxiety, ecstasy, and alienation.

This was the fertile ground from which Expressionism grew—not as a single, unified style, but as a powerful and pervasive impulse to distort reality for emotional effect.

Expressionism is the art of the interior. Where Impressionism concerned itself with the play of light on a surface, Expressionism plunged beneath the surface to explore the tumultuous landscape of the human soul.

.jpg) |

Improvisation 28 (second version) 1912

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons |

It prioritizes subjective perspective over objective reality, using vivid, often non-naturalistic colors, exaggerated forms, and dynamic, jarring brushwork to convey raw, unfiltered emotional experience.

This essay will explore the genesis and core tenets of Expressionism, journey through its two main German branches—Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter—and delve into the seminal works of seven of its most influential artists: Edvard Munch, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Egon Schiele, and Emil Nolde. By examining at least two key paintings from each artist, we will illuminate how Expressionism forever changed the course of art history by asserting that the true purpose of art is not to depict the world as it is, but to evoke the world as it is felt.

The Precursor: Edvard Munch and the Genesis of Angst

While Expressionism fully coalesced in Germany, its spiritual father was the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863–1944). His work, steeped in personal tragedy, illness, and profound existential dread, provided the blueprint for the movement. Munch did not paint people; he painted archetypes of human emotion—love, anxiety, jealousy, and mortality.

Munch’s entire artistic project was what he called "The Frieze of Life," a series of works exploring the depths of human experience. The most iconic of these is undoubtedly The Scream (1893).

Artistic Details of The Scream:

|

Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1910.

Edvard Munch, Public domain, via

Wikimedia Commons

Munch Museum - Oslo, Norway |

This world-famous image is more than a painting; it is a cultural symbol of modern anxiety. The composition is dominated by a swirling, undulating landscape in fiery tones of orange, yellow, and red, meeting a cool, dark blue fjord.

These swirling lines echo the sound waves of the scream itself, immersing the entire world in the figure's panic. Central to this chaos is an androgynous, skull-like figure on a bridge, its hands clasped to its ears, its mouth and eyes wide open in a silent, endless wail of existential terror.

The figure is simplified, almost cartoonish, its form distorted to pure emotional essence. Munch’s use of line is not descriptive but expressive; every curve and streak in the sky reinforces the psychological vibration of the central figure. He wrote of the experience that inspired it: "I felt a great, infinite scream pass through nature." The painting is that feeling made visible, a perfect fusion of internal emotion and external environment.

A less famous but equally powerful work is The Dance of Life (1899-1900). This painting is a poignant meditation on the stages of a woman’s life and the dual nature of love.

Artistic Details of The Dance of Life:

.jpg) |

The dance of life

Edvard Munch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Set under a midnight sun that casts a long, phosphorescent path across the water, the scene depicts couples dancing on a shore.

On the left, a young woman in a white dress, representing innocence and virginity, stands with a hopeful expression.

In the center, a couple in a passionate embrace represents the climax of love and experience; the woman wears red, a color of passion and life force. On the right, a somber woman in black, her face grief-stricken and aged, represents loss, sorrow, and the end of life’s journey. Their dancing is not joyful but ritualistic and fateful.

The figures are elongated and ghostlike, their faces masks of emotion rather than realistic portraits. The entire composition is steeped in symbolism, using color and form to convey the cyclical, often tragic, narrative of human life. The painting exemplifies the Expressionist desire to tackle universal themes through intensely personal and stylized means.

Die Brücke (The Bridge): Raw Urban Energy

In 1905, a group of architecture students in Dresden—Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff—formed Die Brücke (The Bridge). They envisioned themselves as a "bridge" to a new, revolutionary future for art. Rejecting academic tradition, they drew inspiration from medieval German woodcuts, African and Oceanic art, and the raw power of Vincent van Gogh. Their style is characterized by angular distortions, abrasive color contrasts, and a visceral, often confrontational energy that reflected their discomfort with modern urban life.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938) was the group’s leading spirit. His work captures the frenetic pace and psychological tension of the city.

His painting Street, Berlin (1913) is a masterclass in urban alienation.

Artistic Details of Street, Berlin:

The canvas is crowded with towering, elegantly dressed figures parading down a city street. The women, fashionable prostitutes, are rendered with sharp, jagged forms and mask-like faces, their features simplified into cold, impersonal geometric shapes.

Their elongated bodies, cinched at the waist and swathed in luxurious fabrics, resemble predatory birds or exotic plants. The perspective is steep and distorted, creating a claustrophobic, unstable space.

Kirchner uses clashing colors—vibrant pinks, acidic greens, and deep blacks—to heighten the sense of artificiality and decadence.

There is no communication between the figures; they are isolated islands of vanity and desire, moving past one another in a ritual of disconnection. The painting doesn't celebrate the metropolis; it critiques it as a site of dehumanizing spectacle and social anxiety.

Another key work, Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915), is a harrowing document of the psychological devastation of World War I. Drafted into the army, Kirchner suffered a mental and physical breakdown.

Artistic Details of Self-Portrait as a Soldier:

Kirchner paints himself in his uniform, staring directly at the viewer with wide, traumatized eyes. His face is gaunt, painted in sickly greens and yellows, a palette of illness and shock. Most shocking is the severed, bloody stump where his right hand should be—a powerful metaphor for the artist’s fear that the war would destroy his creative ability, his very identity. The background is a chaotic, unfinished whirl of color and form, reflecting his shattered psyche. The figure is cramped and awkwardly positioned, emphasizing his entrapment and vulnerability. This painting is Expressionism at its most raw and autobiographical, using brutal distortion to convey an unimaginable internal reality.

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider): Spiritual Harmony and Abstraction

Concurrently in Munich, another group formed around the Russian émigré Wassily Kandinsky and the German Franz Marc. Named Der Blaue Reiter after their almanac and a recurring motif in their work (Kandinsky loved blue, Marc loved horses), this group was less a unified style and more a gathering of artists seeking spiritual truth through art.

Unlike Die Brücke’s focus on urban angst, Der Blaue Reiter looked to nature, music, and the spiritual realm for harmony. They were pioneers of abstraction, believing that color and form alone, freed from the constraint of depicting objects, could directly express the soul’s vibrations.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) is credited with creating the first purely abstract paintings. He believed in the spiritual power of art, developing a theory that color and form could communicate directly with the human spirit, much like music.

His groundbreaking work Improvisation 28 (second version) (1912) moves far toward abstraction.

Artistic Details of Improvisation 28:

.jpg) |

Improvisation 28 (second version) 1912

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The title itself, drawing a parallel to musical improvisation, is key.

The painting suggests a landscape of cataclysm and renewal—one can perhaps discern a boat, waves, mountains, and figures—but these elements are dissolved into a chaotic and vibrant symphony of color and line.

Bold black strokes, like graphic notations, slash across the canvas, organizing swirling masses of color: fiery reds, calming blues, and luminous yellows. Kandinsky isn’t painting a deluge; he is painting the feeling of apocalyptic energy, the emotional resonance of creation and destruction. The composition is dynamic yet balanced, a visual equivalent of a powerful musical chord. It represents the ultimate Expressionist goal: to bypass the external world and create a direct, visceral communication of emotion through purely painterly means.

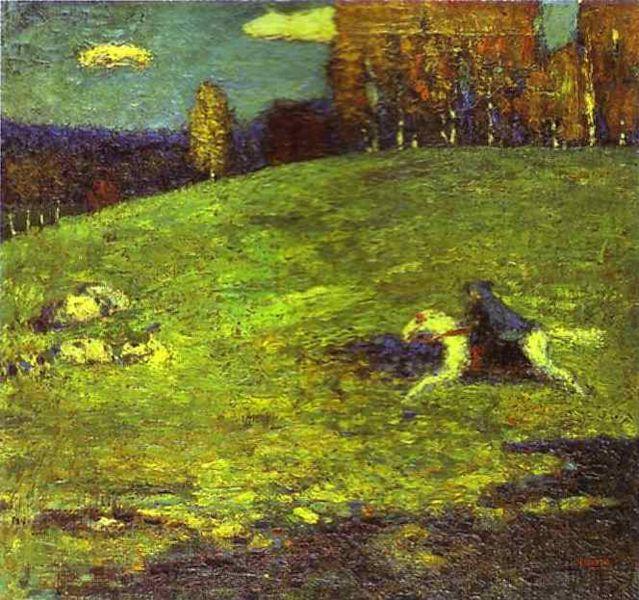

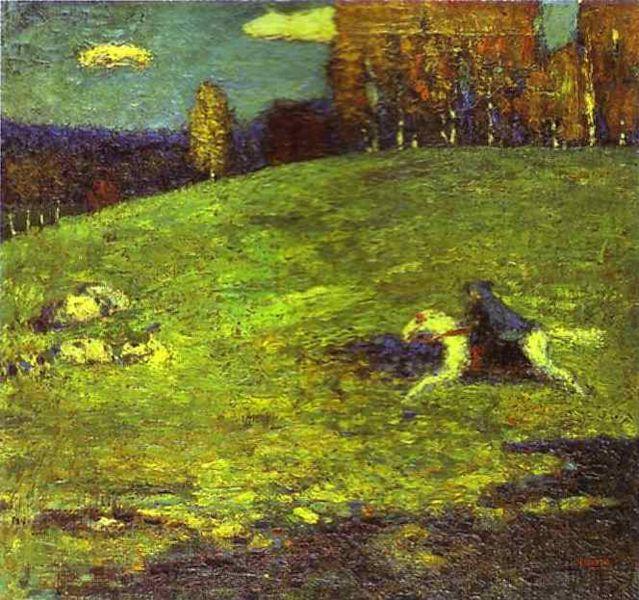

An earlier work, The Blue Rider (1903), gives the group its name and shows the seeds of his later style.

Artistic Details of The Blue Rider:

A lone figure on a galloping white horse, cloaked in blue, charges through a meadow. The landscape is not realistic but a dreamlike field of vibrant, non-naturalistic color.

The rider’s form is simplified, almost blending with the landscape, suggesting a harmonious unity between human, animal, and nature.

The forward momentum, the sense of transcending the mundane, symbolizes the artist’s journey toward a new spiritual art. It is less a depiction of a scene and more a visual poem about freedom, movement, and the pursuit of higher truth.

Franz Marc (1880–1916) sought this spiritual truth through the animal world. He believed animals, living in innocence and harmony with nature, were pure and more spiritual than humanity, which he saw as "ugly." He developed a complex color symbolism: blue was masculine and spiritual, yellow was feminine and joyful, and red was the brutal matter of the world.

His most famous work, The Large Blue Horses (1911), embodies this philosophy perfectly.

Artistic Details of The Large Blue Horses:

|

The Large Blue Horses {{PD-US}}

Walker Art Center , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Walker Art Center Minneapolis, United States |

Three powerful, curvaceous horses, rendered in a luminous, spiritual blue, nestle together in a serene, red-and-green landscape.

Their forms are simplified and rounded, flowing organically into the curves of the hills behind them, creating a sense of profound peace and unity.

The use of color is entirely symbolic; the blue animals represent spirituality and truth, while the red hills represent the earthly world they transcend. The composition is stable and monumental, a vision of an idealized, Edenic world where creatures live in harmony. It is an expression of yearning for a lost paradise, a spiritual refuge from a world Marc saw marching toward destruction.

His later work, Fighting Forms (1914), created on the eve of World War I, is a dramatic departure.

Artistic Details of Fighting Forms:

|

Fighting forms Kämpfende Formen

Franz Marc, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

This is a fully abstract painting, a violent clash of opposing forces.

Sharp, dark, aggressive forms duel with brighter, more defined red and white shapes against a tumultuous background.

It is a painting of pure conflict, devoid of any recognizable imagery. It expresses Marc’s terrifying premonition of the coming war and the shattering of his earlier ideal of harmony. The painting is a powerful testament to Expressionism's ability to convey complex, dark emotions through abstract means. Marc was killed in action at Verdun in 1916, making this painting a tragic and prophetic final statement.

%2C_1910.jpg) |

Kandinsky - Lady (Portrait of Gabriele Münter)

Wassily Kandinsky, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons |

Gabriele Münter (1877–1962) was a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter and Kandinsky’s partner for many years. Her work, often overshadowed historically, possesses a unique clarity, bold use of color, and a masterful sense of composition. She frequently worked in the folk art medium of glass painting (Hinterglas), which influenced her bold outlines and flat planes of color.

A superb example is Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky (1906).

Artistic Details of Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky:

Münter depicts her fellow artist not as a tormented genius but as a contemplative, solid presence. He is shown seated, holding a book, his gaze direct and thoughtful. The true power of the painting lies in its formal execution. Münter uses thick, dark outlines to define the figure and the room’s interior, a technique gleaned from her glass painting. The colors are bright and non-naturalistic but applied in flat, clean areas, creating a sense of structured harmony. The pattern on the wall and the chair add a decorative element that flattens the space, focusing attention on the psychological presence of the sitter. It is a confident, modern portrait that showcases her distinctive contribution to the Expressionist language.

Another key work is Jawlensky and Werefkin (1908-09), a double portrait of fellow Russian Expressionists.

Artistic Details of Jawlensky and Werefkin:

Münter captures the two artists at a table, their faces rendered with simplified, mask-like features. The use of color is dramatic and expressive: Werefkin’s face is a striking green, contrasting with the vibrant reds and yellows of the table and background. The composition is sharply cropped, bringing the viewer intimately close to the subjects. The painting feels both immediate and psychologically charged, a snapshot of the vibrant artistic community in Munich at the time, seen through Münter’s uniquely bold and graphic lens.

The Unflinching Gaze: Egon Schiele's Expressionist Figuration

Austrian artist Egon Schiele (1890–1918) developed a uniquely intense and graphic figurative Expressionism. A protégé of Gustav Klimt, Schiele quickly shed decorative elegance for raw, psychological exposure. His work is renowned for its twisted, emaciated bodies, confrontational poses, and agonizingly honest exploration of sexuality, death, and self.

His Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912) is a masterpiece of egotism and vulnerability.

Artistic Details of Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant:

|

Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (Physalis)

Egon Schiele, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Schiele depicts himself with an arresting, confrontational gaze. His body is angular and bony, the skin rendered in a sickly, yellowish tone, outlined with sharp, jagged black lines that seem to cut into the form.

The fingers are elongated and expressive, contorted into a tense gesture. The orange lantern plant beside him burns like a flame, perhaps symbolizing his own blazing talent and life force.

The background is empty, forcing all attention onto his tormented physique and piercing stare. The portrait is not about flattery but about truth—the truth of physical presence, neurotic energy, and unapologetic self-obsession. It is an anatomy of the soul, laid bare through the distortion of the body.

Another devastating work is The Embrace (Lovers) (1917), a later painting that shows a maturation of his style.

Artistic Details of The Embrace (Lovers):

This painting depicts Schiele and his wife, Edith, locked in a tender yet desperate embrace. Unlike his earlier, more erotic and confrontational works, this painting is about love, intimacy, and mortality. The bodies are still angular and intertwined, but the lines are somewhat softer, the colors more muted. They are wrapped in a large, patterned cloth that seems to both protect and entomb them. Their faces, pressed together, show a profound mixture of love, sadness, and foreboding. Created during Edith's pregnancy and in the shadow of the Spanish flu that would kill them both just a year later, the painting is unbearably poignant. It expresses the ultimate human vulnerability—the desire for connection in the face of inevitable death—with unflinching honesty.

The Elemental Force: Emil Nolde's Religious and Natural Vision

Emil Nolde (1867–1956), associated with Die Brücke for a brief period, was a solitary figure whose work was driven by a deep connection to nature, a fascination with "primitive" art, and a fervent, unorthodox religious faith. His Expressionism is characterized by a brutal, elemental power, achieved through thick, textural application of paint and violently clashing colors.

His nine-part polyptych The Life of Christ (1911-12) is one of the most powerful religious works of the 20th century.

Artistic Details of The Life of Christ (focusing on the central panel):

The central panel, often focusing on Christ among the doctors or the crucifixion, is a whirlwind of intense emotion. Nolde uses lurid, non-naturalistic colors—sickly greens, bloody reds, and deep, ominous blacks—to create a scene of mystical drama. The faces of the figures are grotesque masks, contorted by faith, skepticism, or malice. The brushwork is rough and impulsive, the paint applied thickly as if in a frenzy of creation. This is not a serene, holy scene but a raw, human, and terrifying event. Nolde uses the Expressionist toolbox—color, distortion, and brutal brushwork—to strip away centuries of polished iconography and return to the primal, emotional core of the religious story.

In contrast, his landscape The Sea B (1930) showcases his profound connection to the raw power of nature.

Artistic Details of The Sea B:

This seascape is not a peaceful view but an evocation of the ocean's immense, untamable force. The sky is a brooding mass of dark green and gray, bearing down on a raging sea of thick, impasto strokes of white, blue, and black. The paint itself is physical, like the churning water and wind it represents. There is no horizon line; sky and sea merge into a single tumultuous entity. A single sailboat, a tiny human element, is tossed precariously in the vastness, emphasizing nature's overwhelming power. Nolde doesn't paint the sea; he channels its energy onto the canvas, creating an image that is both terrifying and sublime. It is an expression of awe in the face of the elemental world.

|

The Scream 1910

Edvard Munch, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons |

Conclusion: The Enduring Scream

The Expressionist movement, though often condemned as "degenerate" by the Nazi regime and later overshadowed by newer avant-gardes, left an indelible mark on the history of art.

It fundamentally shifted the purpose of painting from external representation to internal revelation. The artists examined—Munch, Kirchner, Kandinsky, Marc, Münter, Schiele, and Nolde—each in their own way, demonstrated that color, line, and form are not merely descriptive tools but are the very language of emotion itself.

They taught us that a twisted body can speak of psychological trauma more truthfully than a perfectly rendered one; that a green face can convey jealousy or sickness more effectively than a realistic complexion; and that a chaotic swirl of paint can evoke the sound of a scream echoing through nature. They embraced the ugly, the anxious, the spiritual, and the ecstatic—the full spectrum of human experience that had been largely excluded from "fine art."

Their legacy is immense. The Abstract Expressionists of New York, the Neo-Expressionists of the 1980s, and countless contemporary artists continue to walk the bridge they built. In a world that remains complex, often alienating, and emotionally charged, the Expressionist imperative to look inward and express that vision with authenticity and force is as vital today as it was over a century ago. The scream of the soul, first given form on their canvases, continues to resonate.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_1910.jpg)