|

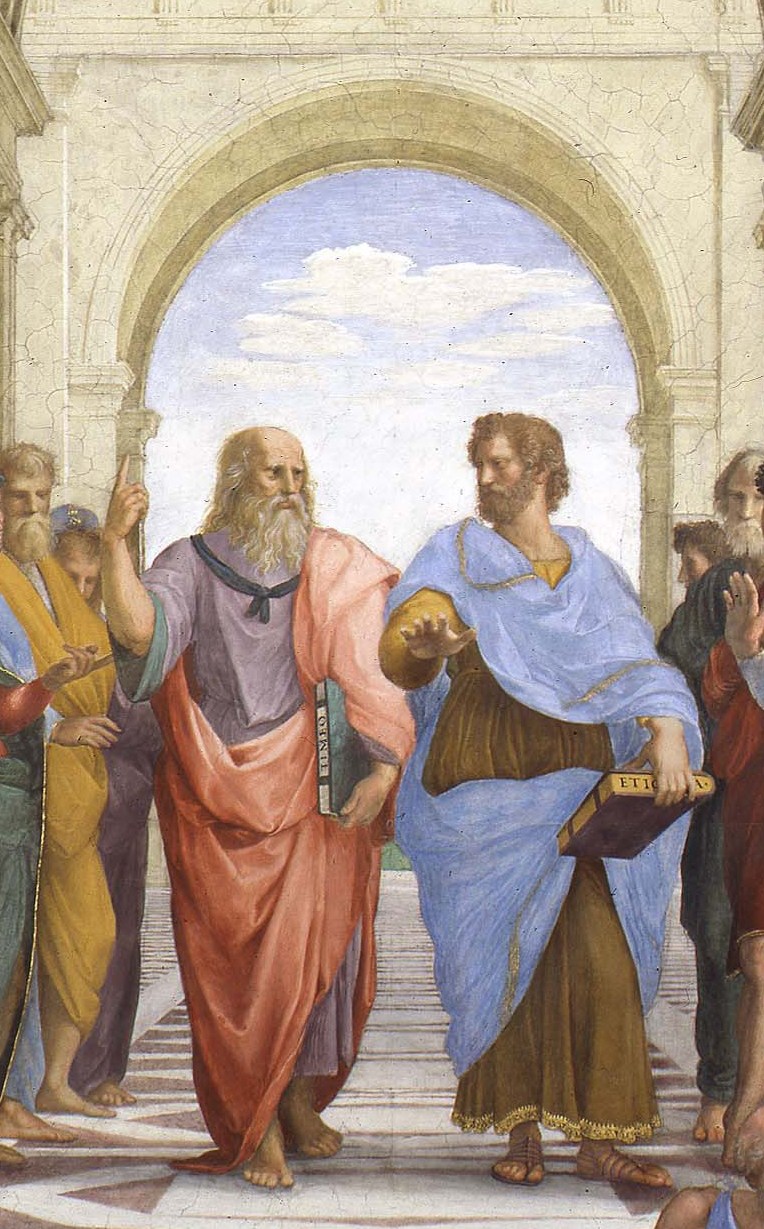

| The School of Athens {{PD-US}} Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Trained initially under Perugino, Raphael swiftly developed a distinctive style that combined the lyrical serenity of his master with the structural rigor of Florentine classicism.

His pilgrimage to Florence catalyzed encounters with the works of profoundly influential contemporaries, while his move to Rome under papal patronage allowed him to execute grand fresco cycles that would define his legacy.

Artistic Contributions

- Mastery

of Composition: Raphael’s works are known for their balanced

structures, often employing pyramidal or symmetrical layouts that guide

the viewer’s eye with natural grace.

- Psychological

Depth: In

portrayals of religious and mythological subjects alike, Raphael captured

nuanced emotion—a tender Madonna’s glance, a meditative philosopher, or a

mythic figure caught in exaltation.

- Architectural

Integration: Especially in his frescoes, Raphael melded

architectural elements—arches, vaults, perspectival spaces—into

compositions, reinforcing spatial coherence and thematic resonance.

- Fusion

of Influences: His art reflects an intelligent fusion of

influences: the soft modeling and sfumato-like transitions reminiscent of

one genius of the time; the dramatic anatomy and muscular vitality echo

another; yet Raphael shaped these into a luminous, serene style uniquely

his own.

- Impact

on Artistic Academia: His methodical approach to composition and figure

drawing influenced generations of artists, establishing a model for

classical academic art in the centuries that followed.

Five Masterpieces

1. The School of Athens

(1509–1511)

|

| The School of Athens Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Painted as a fresco in the papal apartments, this work stands as Raphael's masterpiece, showcasing a grand assembly of ancient philosophers in an imposing architectural setting.

At the center, two iconic figures stride—the contemplative idealist beside the pragmatic empirical thinker—embodying the harmony of thought.

Around them, scholars, mathematicians, and visionaries interact in intellectual pursuit. The composition is underpinned by rigorous perspective, enhancing the unity of figures and space.

Raphael even includes a discreet self-portrait, engaging the viewer directly, which speaks to his confidence and situates him among the great minds of antiquity. The fresco crystallizes Renaissance ideals: reverence for classical knowledge, visual clarity, and intellectual balance. Its architectural arches and vaults echo the grandeur of ancient design, while the vibrant humanity of the figures anchors the scene in Renaissance humanism.

2. Madonna della Seggiola

(c. 1513–1514)

|

| Madonna della Seggiola Francesco Bini, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

This circular (tondo) painting portrays the Virgin seated with the Christ child nestled in her arms, while a devout young saint watches.

The intimate composition breaks from traditional pyramidal arrangements by embracing the rounded format, drawing the figures close into shared warmth. The masterful use of naturalistic flesh tones and harmonious coloring creates a palpable sense of maternal warmth.

Notably, Raphael omits the detailed background typical of religious painting; the dark, featureless backdrop sharpens focus on the emotional bonds between mother, child, and witness.

The painting exemplifies

comfort and serenity, revolutionizing how Madonnas were presented—less as

icons, more as human beings in devotional quiet. It also influenced portraiture

of that era, particularly in how figures physically occupy space and convey

psychological presence.

3. La Belle Jardinière

(1507–1508)

This early Florentine Madonna depicts the Virgin tenderly supporting the

Christ child, while the youthful saint looks on with reverent devotion. Raphael

constructs a pyramid of forms, centering the Virgin’s serene gaze and gently

animated gestures. A luminous garden unfolds behind them, offering a

naturalistic environment infused with spiritual calm. The technique draws from

earlier masters of the period, with clear, unified composition and soft

modeling of forms—an early triumph of his Florentine phase. The triangular

grouping emphasizes maternal protection, while symbolic elements like the faint

halos and sacred book foreshadow narratives of passion. This painting signals

Raphael’s transition into Renaissance maturity, blending a devotional hush with

rich, atmospheric color.

4. St. Catherine of Alexandria (c. 1507)

|

| St. Catherine of Alexandria Raphael, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The painting depicts the saint in a moment of spiritual ecstasy, her gaze lifted heavenward as she leans gently against the wheel—her traditional attribute symbolizing martyrdom. Raphael renders her with an elegant contrapposto, a pose inspired by classical sculpture, which imbues the figure with both dignity and vitality.

The soft modeling of her features, luminous skin tones, and flowing drapery reveal his assimilation of Florentine innovations in anatomy and chiaroscuro.

Unlike static medieval representations, this Catherine exudes inner life; her upward glance conveys serene devotion rather than suffering. The serene blue sky and diffused light create a backdrop that elevates the saint’s spiritual focus. This painting demonstrates Raphael’s ability to fuse classical balance, religious reverence, and human emotion, qualities that defined his mature style.

5. La Fornarina (1518–1519)

In this intimate portrait, Raphael depicts a young woman—traditionally

thought to be his lover—wearing a turban and a bare shoulder, gazing

seductively outward. The painting is celebrated for its sensuality and tender

realism: soft flesh, luminous eyes, and a richness of texture in fabric and

skin. Her expression is both personal and enigmatic, straddling the line

between portraiture and idealized beauty. The work is suggestive in tone, less

devotional than personal, and has sparked fascination precisely because of its

ambiguous blend of a real person and a timeless feminine beauty. It contributes

to the emotional breadth of Raphael’s oeuvre and reflects his capacity to

represent personal intimacy with equal artistry to grand frescoes.

Comparison with Two

Contemporaries

|

| The Last Supper Leonardo da Vinci, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo, slightly older, was a polymath—painter, inventor, scientist—who approached art as a scientific means to understand nature.

His chiaroscuro, sfumato, and anatomical realism introduced profound subtlety and softness to forms. Raphael absorbed these techniques in creating nuanced human expressions and spatial depth.

However, unlike Leonardo’s often enigmatic and highly

experimental compositions, Raphael's canvases prioritize clarity and

compositional harmony. His figures are more accessible, arrangements more

structured, ultimately giving Raphael a classical serenity where Leonardo’s

genius leans toward poetic mystery.

Michelangelo Buonarroti

|

| Libyan Sibyl Michelangelo, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Michelangelo’s art, focusing on sculptural anatomy and muscular intensity, projected raw physicality and dramatic tension. Raphael admired but diverged—while Michelangelo imbued figures with monumental energy, Raphael leaned toward poised elegance and emotional balance.

Yet he absorbed Michelangelo’s influence into his own style: the anatomy of his figures became more expressive, and the gestures more meaningful. Instead of dramatic contortion, Raphael preferred measured grace.

Thus, Raphael’s works often feel more

composed and harmonious, even when engaging with narrative or religious themes,

compared to Michelangelo’s visceral intensity.

Conclusion

Raphael’s contribution to the art of painting lies in his unique melding of the serene beauty of classical form, the emotional resonance of human connection, and the intellectual ideals of the High Renaissance. From stately frescoes to intimate portraits, his art is characterized by compositional mastery, psychological subtlety, and an evolving style informed—but never overshadowed—by his illustrious peers.

His five works—The School of Athens,

Madonna della Seggiola, La Belle Jardinière, The Triumph of

Galatea, and La Fornarina—stand as vivid monuments to his

artistry. By blending the innovations of Leonardo and Michelangelo with his own

balanced vision, Raphael forged an enduring legacy that shaped the trajectory

of Western art.

Suggested Sources (for

reference only)

- Encyclopaedia

Britannica – Raphael

- National

Gallery of Art – Raphael

- The

Guardian—Renaissance exhibitions

- Artnet

News – Raphael’s greatest works

- Artsper

Blog – Raphael paintings

- Artsy—Raphael’s key artworks

- History

and Art—Renaissance overview