1. Introduction

|

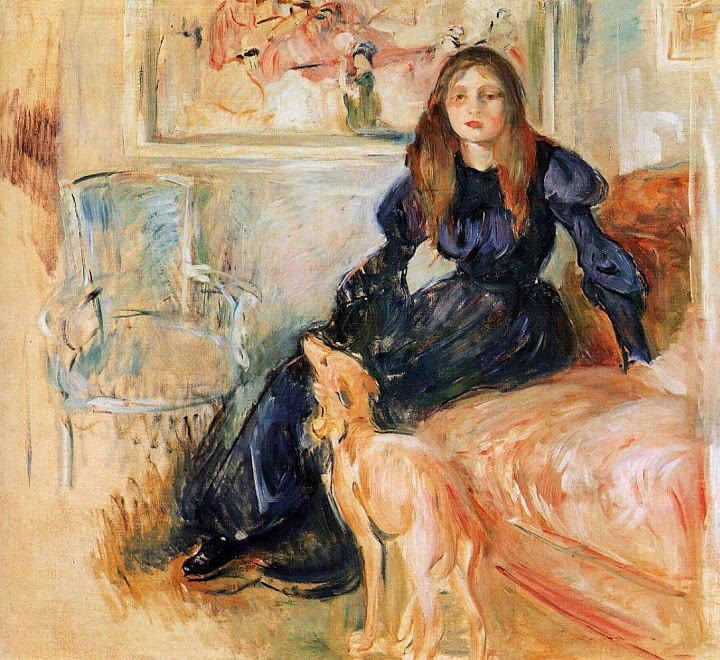

Berthe Morisot

Édouard Manet, Public domain,

via Wikimedia Commons

Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) was one of the central figures of French Impressionism, a movement that transformed painting in the late nineteenth century. At a time when the art world was dominated by men and academic conventions, she carved out a space of her own, painting luminous depictions of women, children, gardens, and interiors.

Her work has often been described as delicate, but in truth it is daring—breaking rules of finish, form, and subject matter to capture the fleeting sensations of modern life.

Morisot was the only woman to exhibit consistently with the Impressionists from their first group show in 1874 until the 1880s. She was at once part of the radical avant-garde and deeply connected to the domestic and personal world, a combination that gave her art its unique force. Unlike her male colleagues, who often turned their gaze toward bustling boulevards, cafés, or grand landscapes, Morisot turned her brush to intimate interiors and subtle exchanges, showing that the private sphere was just as modern as the public one.

Today, Berthe Morisot is recognized not only as an important woman artist but also as one of the most innovative Impressionists in her own right. Her paintings shimmer with light and immediacy, offering a vision of modern life that feels personal and universal at once. As her reputation continues to grow, museums and collectors have placed her firmly among the giants of her era, while her art remains fresh and relevant to audiences around the world.

2. Early Life and Artistic Training

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot was born on January 14, 1841, in Bourges, a provincial city in central France. She came from a well-to-do bourgeois family, which afforded her both privilege and restriction. On one hand, her comfortable background gave her access to private tutors and the leisure to pursue artistic training. On the other, her social position and gender imposed strict limits on where she could study and what she could paint. Women were excluded from the École des Beaux-Arts, the premier art academy in Paris, and were discouraged from attending life-drawing classes with nude models.

Despite these barriers, Morisot’s parents supported her artistic ambitions. Alongside her sister Edma, she began formal lessons in drawing and painting. Their studies led them into contact with Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, a leading figure of the Barbizon school of landscape painting. Corot’s influence proved formative: he encouraged his students to paint outdoors, directly observing light and nature. This practice of plein air painting—then considered unconventional—prepared Morisot to embrace the radical aesthetics of Impressionism a decade later.

Morisot showed great promise early on, mastering delicate but confident brushwork and a keen eye for atmospheric effects. She began submitting works to the official Salon, the state-sponsored annual exhibition that defined artistic reputations in France. Acceptance at the Salon was a coveted marker of legitimacy, and Morisot succeeded in having several works displayed during the 1860s. Yet even as she participated in this establishment venue, she felt restless with its rigid standards of finish and subject matter.

Her artistic education during these years instilled both technical skill and a sense of constraint. She knew firsthand how narrow the acceptable paths for a woman artist could be, but rather than discouraging her, these limitations sharpened her determination. By the early 1870s, Morisot had cultivated a style that was distinct from academic convention—fresher, freer, and more responsive to lived experience. These qualities would soon align her with a new generation of artists challenging the very foundations of French painting.

3. Influences and the Road to Impressionism

|

For the holiday season

Berthe Morisot, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Berthe Morisot’s artistic identity was shaped by several key influences, each of which contributed to her mature style.

first, as mentioned, was Corot and the Barbizon painters. They emphasized working directly from nature, capturing the play of light across trees, fields, and skies. Morisot absorbed their lesson in observation but translated it into her own language of subtlety and brevity.

Unlike Corot, whose tonal harmonies often leaned toward muted earth colors, Morisot gradually moved toward brighter, more luminous palettes.

The second influence was Édouard Manet, one of the boldest innovators of nineteenth-century painting. Morisot first met Manet in 1868, and their artistic exchange was immediate and profound. She modeled for him on several occasions—appearing in paintings such as The Balcony and Repose—but their relationship went beyond muse and painter. Morisot challenged Manet, urging him to loosen his brushwork and embrace spontaneity, while she herself absorbed his daring sense of modern subject matter. In 1874, she married Manet’s brother Eugène, further cementing her connection to the family and strengthening her artistic network.

A third and subtler influence was the legacy of eighteenth-century French painting, especially the Rococo masters like François Boucher and Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Morisot admired their light touch, pastel colors, and playful intimacy, and one can see echoes of Rococo delicacy in her Impressionist brushwork. Yet unlike her Rococo predecessors, Morisot depicted the lived realities of modern women, avoiding allegory and myth.

By the early 1870s, Morisot had grown disillusioned with the Salon system. She and a group of like-minded painters—including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro—decided to mount their own exhibition. In 1874, they held the first Impressionist show, a groundbreaking event that shocked critics but set the course of modern art. Morisot’s participation was crucial: she was the only woman included in this initial lineup and would continue to show with the Impressionists throughout the following decade, proving her unwavering commitment to their shared vision.

4. The Impressionist Era and Morisot’s Place in It

|

Berthe Morisot,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Cradle -- Musée d'Orsay |

Berthe Morisot, a central figure in the Impressionist movement, brought a revolutionary freshness to depictions of women and children. In The Cradle, she portrays her sister Edma watching over her sleeping infant.

The painting captures a deeply private moment of maternal tenderness. Unlike male Impressionists who often painted urban scenes, Morisot chose a quiet domestic interior.

The mother's gaze is contemplative, gentle, and protective, emphasizing the psychological depth of motherhood.

Artistic Elements:

Soft, feathery brushstrokes and a light-filled palette embody the ephemeral beauty of the scene.

The gauze veil over the cradle is painted with remarkable translucency, showing Morisot’s technical finesse.

The diagonal gaze from mother to child creates emotional connectivity.

Modern Value:

Morisot’s works have seen a dramatic rise in value. The Cradle is considered one of her masterpieces, housed in the Musée d'Orsay. In the art market, her paintings now command prices of $2 million to over $10 million, particularly those featuring domestic scenes with women and children.Impressionism was not only a style but a movement of rebellion.

Its practitioners rejected the polished canvases of academic art and the historical or mythological subjects preferred by the Salon. Instead, they sought to capture life as it was happening: city streets, suburban leisure, shifting weather, and the glow of afternoon light.

Morisot, fully aligned with this philosophy, brought to the movement a voice that was both distinctly feminine and universally modern.

While her male colleagues often gravitated to landscapes, urban boulevards, or cafés, Morisot focused on domestic spaces and private life. She painted women at their toilette, children at play, and families gathered in gardens or drawing rooms.

To dismiss these subjects as trivial would be a mistake; Morisot demonstrated that the private world was just as much a part of modern life as the public sphere. Her paintings of balconies, for example, often show figures looking outward, poised between interior and exterior, symbolizing the permeability of these two domains.

|

Young Woman Knitting

Berthe Morisot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA |

Morisot’s presence at Impressionist exhibitions also carried symbolic weight. The movement itself was criticized as frivolous and unfinished, and Morisot’s participation opened it to further dismissal by critics who associated femininity with amateurism. Yet she proved herself indispensable, showing some of the boldest works in these shows and receiving praise from peers who recognized her talent.

Degas, for example, respected her vision, while Renoir admired the lightness of her brush.

By the late 1870s and 1880s, Morisot’s reputation was firmly established among avant-garde circles. She remained less commercially successful than Monet or Renoir, but her artistic authority was unquestioned within the movement. More importantly, she had carved out a space for female creativity at the very heart of modern painting.

5. Artistic Style and Signature Subjects

Berthe Morisot’s artistic style can be recognized immediately by its lightness, speed, and atmosphere. She worked with thin, fluid brushstrokes that gave her canvases a sense of air and motion. Unlike academic painters who carefully modeled forms with shadows, Morisot often allowed edges to blur, suggesting rather than delineating shapes.

This approach conveyed the fleeting quality of perception, as though the viewer had entered the room or garden just at the moment of the sitter’s gesture.

Her color palette leaned toward high-key tones: soft pinks, pale greens, lavender, silver, and pearl whites. White, in particular, became a hallmark of her work. In her hands, white was never flat—it was tinged with blue, violet, or rose, creating the sensation of fabric shimmering under light. Her ability to capture the texture of muslin, lace, or silk rivaled any of her contemporaries.

Morisot’s signature subjects centered on women, children, and domestic life. Far from being mere sentimental scenes, these paintings present modern identity in intimate terms. Works like The Cradle or Young Girl Reading portray not only the sitters but also the quiet spaces of thought, care, and routine that define human life. She also painted leisure scenes—boating, garden strolls, summer holidays—that reflected the expansion of bourgeois life in late nineteenth-century France.

A recurring motif in her work is the balcony, which often frames a woman gazing outward. This architectural threshold becomes a metaphor for her art itself: standing between inside and outside, Morisot’s paintings embody the merging of private life with the broader currents of modern society.

6. Historical and Social Context

Morisot painted during one of the most dynamic periods in French history. Paris was undergoing massive transformation under Baron Haussmann, who reshaped the city with wide boulevards, parks, and modern infrastructure. The Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and the violent upheaval of the Paris Commune left lasting scars, and the nation was grappling with rapid industrialization, shifting class structures, and evolving gender roles.

For women, the art world remained a challenging environment. They were excluded from formal academies, denied access to life-drawing classes, and often discouraged from pursuing professional careers. Those who persisted were typically steered toward “feminine” subjects like still life or portraiture. Morisot, while accepting domestic subject matter, imbued it with radical freshness. She showed that sewing, reading, or child-rearing could be as worthy of modern painting as a bustling café or dramatic landscape.

Her art also reflects the growth of middle-class leisure culture. As trains expanded travel, Parisians flocked to suburban gardens and coastal resorts, settings that appear frequently in Impressionist painting. Morisot participated fully in this culture, painting scenes of boating, picnics, and vacations, but always filtered through her lens of intimacy and light.

In this historical context, Morisot’s work takes on even greater significance. By focusing on women’s spaces and experiences, she challenged the hierarchy of subjects that had long defined art. Her paintings assert that modernity was not only built in streets and factories but also lived in drawing rooms and nurseries.

7. Comparisons with Contemporaries

Morisot and Édouard Manet:

Manet was Morisot’s closest artistic counterpart. He favored provocative public subjects—barmaids, café singers, bullfights—painted with bold contrasts. Morisot, by contrast, explored private interiors and gentle exchanges. Where Manet shocks with blunt modernity, Morisot entrances with intimacy. Yet both share loose brushwork, daring compositions, and a commitment to painting the present.

Morisot and Claude Monet:

Monet sought to dissolve objects into atmosphere, painting landscapes in changing light. Morisot applied similar principles indoors, treating human figures as part of the surrounding air. Monet’s canvases could feel monumental in their focus on rivers, gardens, and cathedrals; Morisot’s paintings, smaller in scale, captured equally monumental truths about perception and time in domestic settings.

Morisot and Mary Cassatt:

Mary Cassatt, another woman Impressionist, also painted women and children. However, Cassatt’s style was firmer, influenced by Japanese prints, with strong lines and structured compositions. Morisot’s canvases, in contrast, shimmer with blurred edges and lightness. Together, they broadened Impressionism to include the complexity of women’s lives, though their approaches differed in tone.

Morisot and Edgar Degas:

Degas’s art focused on performers, races, and rehearsals—public spectacles shaped by discipline and display. Morisot, on the other hand, painted the quiet theater of daily life. Degas emphasized structure and line; Morisot emphasized atmosphere and fleeting gesture. Their differences highlight the breadth of Impressionism as a movement.

8. Reception and Critical Legacy

During her lifetime, Berthe Morisot’s art was both admired and underestimated. Many critics described her work as “feminine,” using the term dismissively to suggest it was delicate or slight. Yet her contemporaries within the Impressionist circle respected her profoundly. Degas valued her opinion, and Renoir spoke of her lightness as unmatched.

After her death in 1895, Morisot’s reputation waned, overshadowed by the fame of Monet, Renoir, and Manet. For much of the twentieth century, art history textbooks mentioned her only briefly, if at all. However, the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries witnessed a reappraisal of her contributions. Feminist art historians, museum curators, and collectors began to highlight her importance, recognizing her as a central figure rather than a peripheral one.

Major exhibitions devoted to Morisot have helped cement her reputation. Museums across Europe and North America have staged retrospectives, emphasizing not only her role as a woman painter but also her technical innovation and modern vision. Today, she is seen as one of the essential Impressionists, whose work cannot be separated from the movement’s achievements.

9. The Value of Morisot’s Paintings Today

The art market has mirrored this growing recognition. For decades, Morisot’s paintings sold for far less than those of her male colleagues. In recent years, however, her works have reached record prices. A standout moment came in 2013, when her painting Après le déjeuner sold for nearly $11 million, setting a benchmark for her market.

Today, her oils regularly fetch millions of dollars at major auctions. Works featuring her daughter Julie, balcony scenes, or quintessential Impressionist interiors are especially prized. Collectors value not only their beauty but also their rarity, as Morisot’s oeuvre is relatively small compared to that of Monet or Renoir. Drawings, watercolors, and prints are also collected, offering more accessible entry points into her market.

Museums, too, have actively sought her work. Institutions such as the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., hold important examples, ensuring her visibility to international audiences. The combination of scholarly attention, exhibition exposure, and market performance has firmly established Morisot as one of the most significant artists of her century.

10. Conclusion

Berthe Morisot stands as a pioneer of Impressionism and one of the most original painters of the nineteenth century. From her early training with Corot to her mature years among the Impressionists, she pursued a vision that was both deeply personal and profoundly modern. Her paintings of women, children, gardens, and interiors capture the fleeting nature of life with unmatched sensitivity, turning domestic spaces into theaters of light and perception.

Compared with contemporaries like Manet, Monet, Cassatt, and Degas, Morisot carved out her own territory—neither monumental like Monet nor provocative like Manet, but equally revolutionary in her insistence that everyday life, especially women’s lives, belonged on the canvas of modern art.

Her legacy has grown steadily over the past century, with museums, scholars, and collectors recognizing her as a central Impressionist innovator. The rising value of her paintings in the art market reflects not only financial demand but also cultural acknowledgment of her lasting importance.

In Morisot’s paintings, light breathes through fabric, skin, and air; gestures hover in suspension; and life is caught in the instant before it changes. This ability to seize the ephemeral makes her art timeless. Today, as we look at her works, we encounter not only the brilliance of Impressionism but also the enduring spirit of an artist who dared to see modernity in the quiet, intimate moments of human existence.

Key takeaways:

-

Era: Founding Impressionist (active 1870s–1890s).

-

Style: High-key color, swift brushwork, and luminous “plein-air interiors.”

-

Influences: Corot’s plein air and Manet’s modernity, plus dialogue across the Impressionist circle.

-

Historical context: Modernizing Paris; constraints and possibilities for women artists; domestic spaces as modern subjects.

-

Comparisons: Manet (public modernity) vs. Morisot (intimate modernity); Monet’s landscapes vs. Morisot’s interiors; Cassatt’s structure vs. Morisot’s air.

-

Value: Record of c. $10.9M in 2013; sustained six- to seven-figure results across media in recent seasons.