|

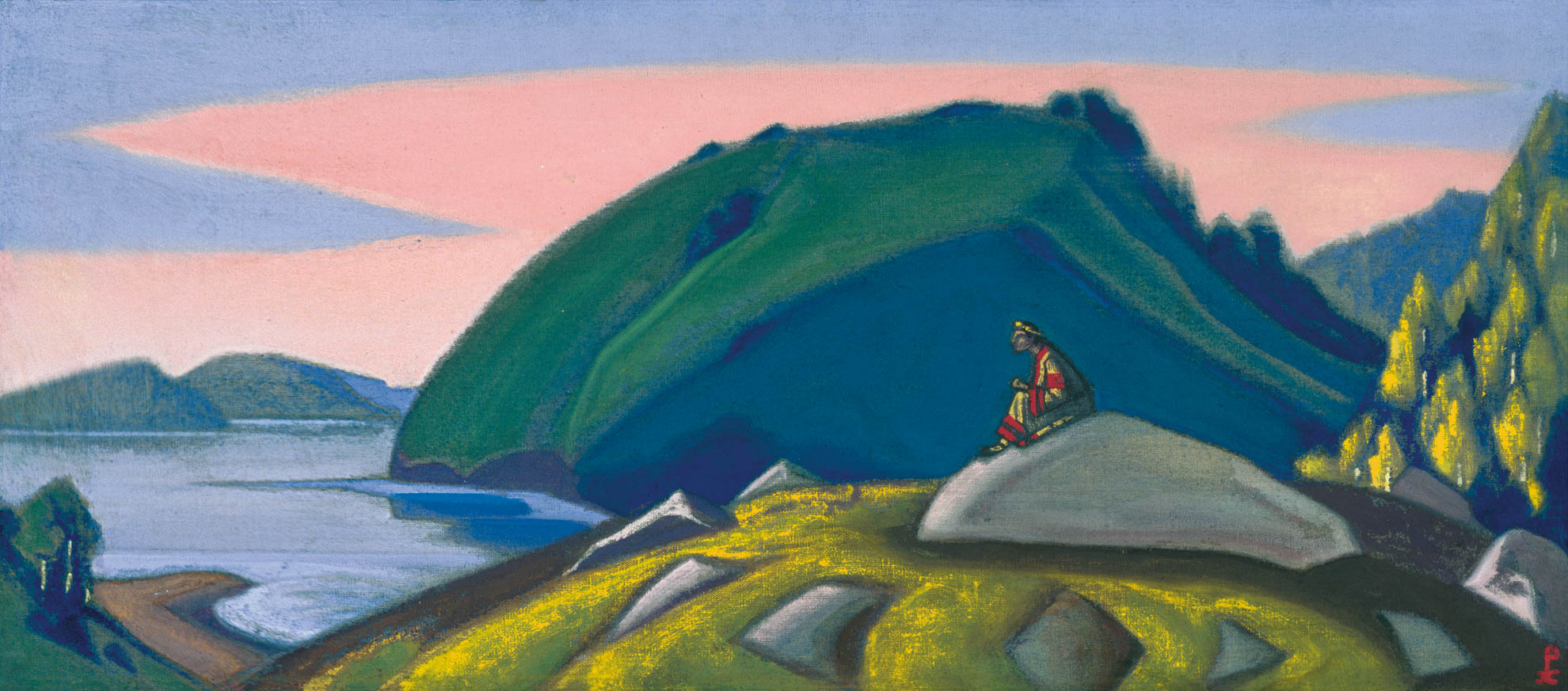

Nicholas Roerich, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons The Rite of Spring |

Here are some of the paintings of the northern part of India. The artist was not an India born person.

Father was German. He was a lawyer. Mother was Russian. They lived in the city of Saint Petersburg. This city was formerly known as Petrograd (1914-1924). Yes, it was known as Leningrad (1924-1991), too. But we would call the city of Saint Petersburg.

You step into the world of Nicholas Roerich, and suddenly, borders dissolve. You no longer belong to just one nation, and neither did he. Born into a union that gave the world a soul of uncommon vision, Roerich became more than a painter, more than a traveler—he became a seeker. As you follow the thread of his life, you feel that his journey was never merely about crossing physical landscapes; it was about traversing the inner realms of the human spirit.

You imagine him walking—yes, walking—across mountains, valleys, and deserts. Sometimes he did just that, covering miles on his own two feet. This wasn’t wanderlust alone. You sense it was something deeper, almost as if Providence whispered in his ear, telling him his life was to be a canvas painted with countless experiences. Among those experiences, one pursuit burned brightest: the noble art of painting.

Now, picture yourself standing before one of his most evocative works, The Brahmaputra. You feel the pull of the river without moving an inch. The painting doesn’t demand your attention—it invites it, drawing you into a meditative state. You begin to suspect that Roerich himself must have been in a similar mood of deep reflection while creating it.

|

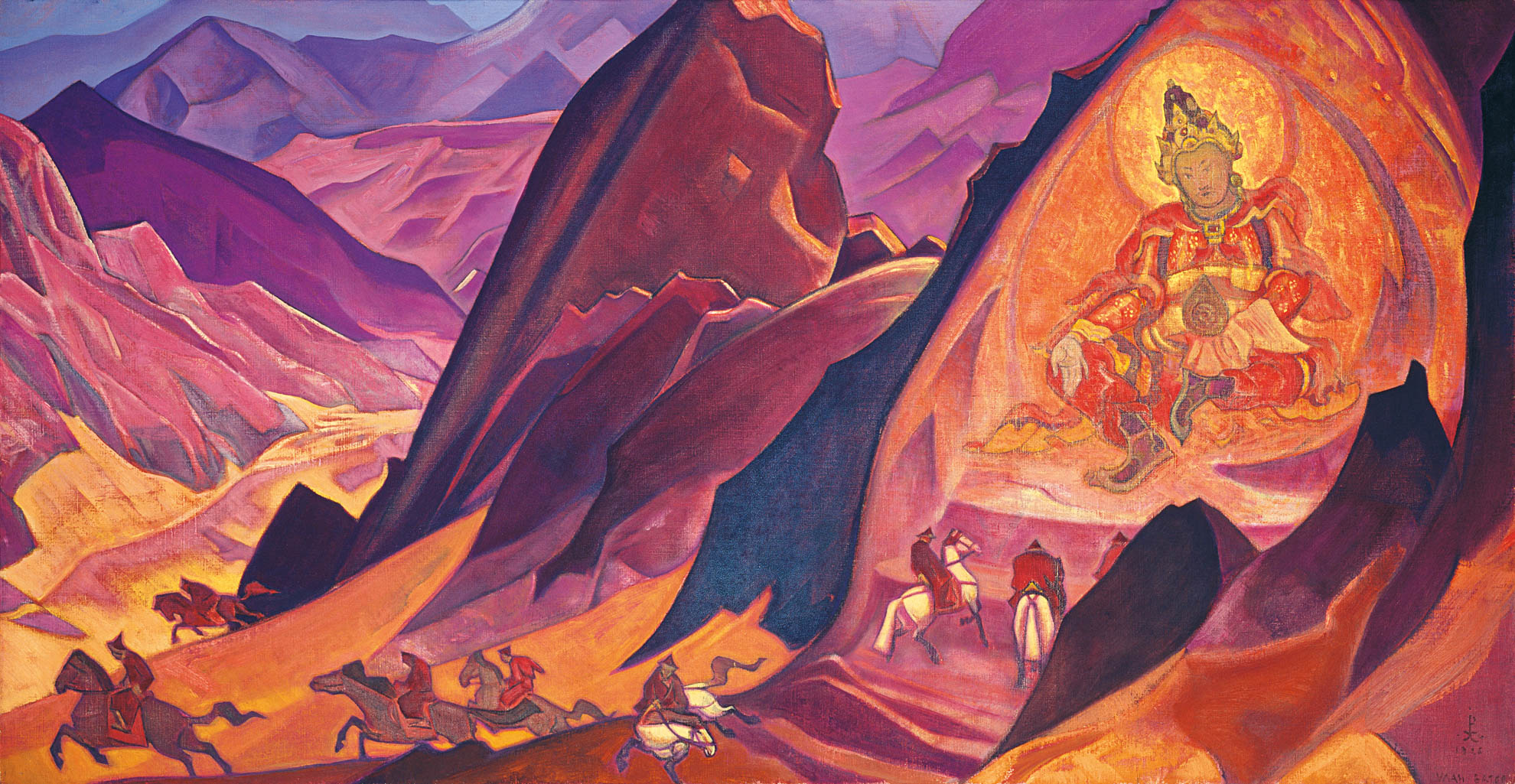

Nicholas Roerich, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Order of Rigden Djapo |

At first glance, the forms in The Brahmaputra are simple. But the simplicity is deceptive. Within those spare outlines lies an unfolding drama, brought to life through the richness of blue. The hue is cool yet commanding, restrained yet full of quiet power. You notice how it transforms the scene into something more than a representation—it becomes a mirror for contemplation. The more you look, the more you realize this is not a painting you simply see; it’s one you experience.

Roerich’s journeys often brought him to India, and here his brush found new mountains to climb. The Himalayan peaks became his muses. You can almost see him standing before them, tracing their lines with his gaze, sensing the harmony of their forms. Few artists have painted the Himalayas with such reverence, and you feel that his connection went beyond the visual—it was spiritual. He didn’t just capture the peaks; he conversed with them.

|

Nicholas Roerich, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons Nag Lake. Kashmir |

If you’ve been fortunate enough to see great works before, you start to recognize patterns—moments where the artist’s vision crystallized into a perfect expression.

You find yourself hunting for that very moment in Roerich’s work—the instant when brush met canvas and something eternal was born. In every well-crafted piece, you expect to find the same essential ingredients: form, mood, harmony, and the elusive spirit of the moment. With Roerich, you find them all.

Artists often speak of being overtaken by a force when working with color, a kind of inner compulsion that guides their hand. As you stand before The Brahmaputra, you can feel that force at work. It’s as though the blues chose themselves, as though the forms arranged themselves, driven by some instinct Roerich could only follow, not command.

You walk away from the painting but carry it with you. You realize that art like this is more than visual pleasure—it’s a conversation with the soul. Through his travels, Roerich gathered not just images but essences. He distilled them into his canvases, leaving you with pieces that are at once deeply personal and universally resonant.

When you think of Nicholas Roerich now, you don’t just think of an artist. You think of a man whose life was a pilgrimage, whose footsteps carried him across continents and whose vision carried him into realms beyond sight. You feel that, by looking at his work, you too have traveled—through time, across landscapes, into the quiet heart of beauty itself.

The Artist: For an artist, a painting, the fruit of his or her labour, is much more than a painted surface. Through the medium of colours, he or she tries to infuse the order of nature in a painting. It is the order that nature has in it, intrinsically embedded within.

|

Nicholas Roerich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

The writers and poets have a poetic license from the Almighty God. They can take extra liberty while executing their art,

their inner talent. The artists have this type of license for using their

artistic skills to their best. While acting upon this special authority, poetic

licence, the painters impose the forms in their paintings. They do so by making

the altered state of the forms.

However, the trend of imposing such transformed forms has never remained

static. It has undergone constant change since the days of ancient artists’ work

to the modern stock of artistic outputs. And that is the reason why

the forms on the canvases have always kept changing. The shapes of the objects

painted have transformed themselves as per the choices of the artists like

Picasso and Van Gogh.

How to Communicate Through Forms: The painters' ideas about

the forms, as they perceived them, are quite complex. It varies with the

experience of each and every artist. Their method of communication is unique in

nature, so far as the great painters are concerned. Some artists believe that

the defined lines of the objects in the painting are the foremost necessity.

The Renaissance painters did believe so. Some artists regard the definite

lines are so important: the modern artists, including those of the

impressionist clan.

|

Nicholas Roerich, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons "The Great Flag of the Orient" series |

Kang-chen-dzod-nga – Five Treasures of Great Snows. Paintings of the Himalayan Mountain "Mount of Five Treasures (Two Worlds)".

And why is this sublime mountain called Five Treasures of Great Snows? Because it contains a store of the five most precious things in the world. They contain gold, diamonds, and rubies under their peaked surfaces. The old East values other treasures. It is said that a time would come when the famine element would overcome the whole world. At that time, a man would appear and he would unlock the giant gate of these vast treasuries and nurture the entire mankind.

Certainly, you understand that

this man will nourish humanity not physically, but with spiritual food. - Nicholas

Roerich.

The job of an artist is a complex one, in a sense. The painter’s work, and

the purpose for which he or she paints, is somehow to remake the mental images

he or she has made on seeing a scene or the objects.

The Artist Acting As A Bridge: The artist’s desire is to

share his or her experience through the art that would churn out a note of

recognition in the viewers’ eyes. Thus, the work of art constructs a bridge

between the viewers and the artist, communicating the inner traffic of an

artist’s mind to the art lovers’ eyes.

Thus, the piece of art that was merely an image in the artist’s mind, the painting that was only a child of intuition, becomes available to those who value the same.