Miniature Painting in Rajasthan: Royal Patronage, Styles, and Masterpieces

|

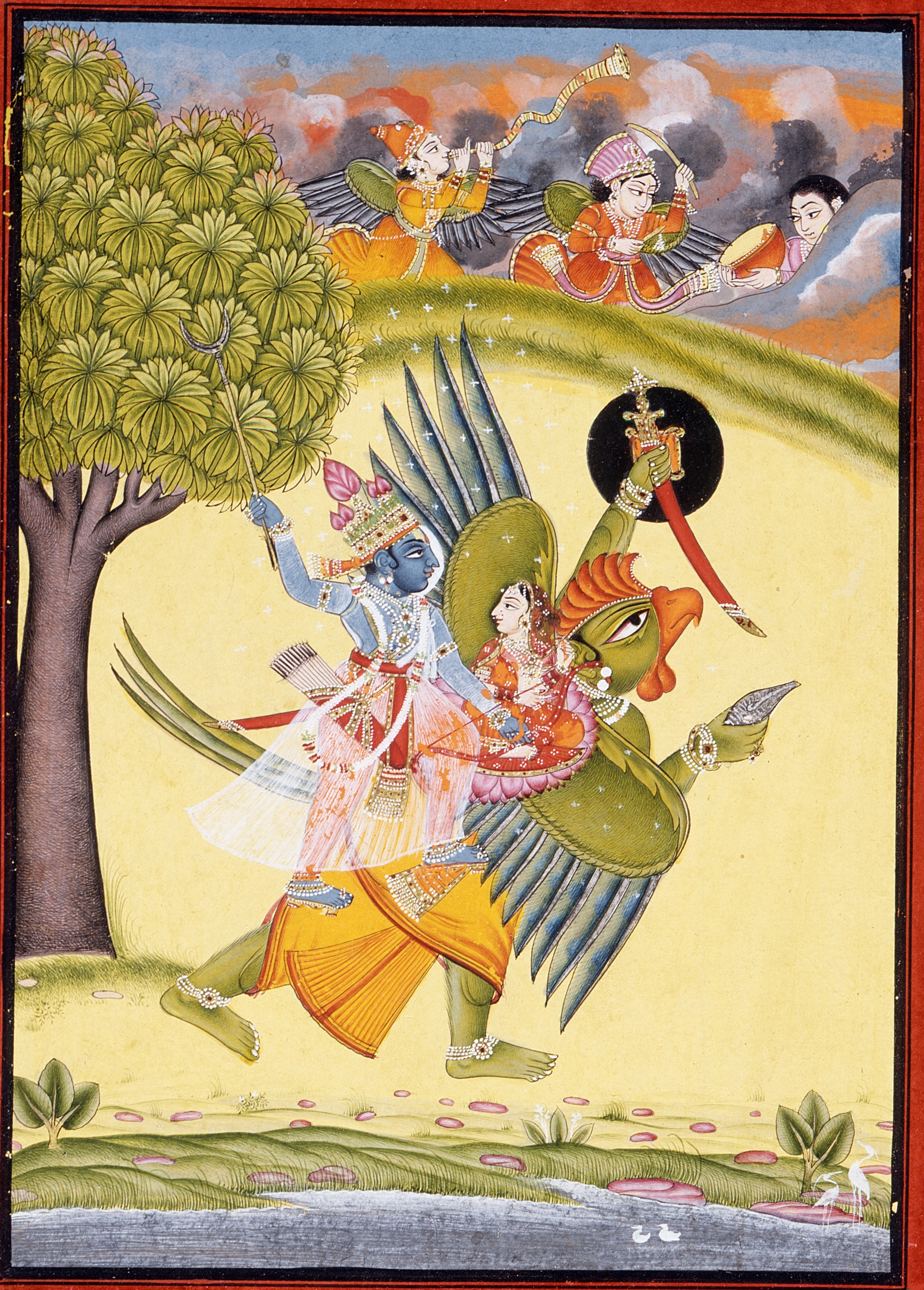

Unknown artist from Bundi, Rajasthan, India, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Flourishing under the patronage of Rajput kings from the 16th century onward, Rajasthani miniature painting was not merely a decorative pursuit but a complex and refined visual language that chronicled heroism, divine love, courtly grandeur, spiritual longing, and the rhythms of nature.

- Watercolor, Opaque watercolor,

- gold, and silver on paper Sheet

From the arid lands of Mewar to the hilly fortresses of Bundi, and from the princely courts of Bikaner to the rich ateliers of Jaipur, each school of painting emerged with its own distinctive aesthetic, bound together by a shared devotion to intricate detail, luminous color, and expressive storytelling.

This essay explores the development of miniature painting in Rajasthan, delving into the distinctive stylistic traditions of its principal schools, while analyzing ten representative artworks that reveal the emotional depth, technical mastery, and historical breadth of this artistic legacy.

The Rise of Rajasthani Miniature Painting

The genesis of Rajasthani miniature painting can be traced to the 16th century when the declining influence of the Delhi Sultanate and the rise of autonomous Rajput states created fertile ground for regional artistic expressions. While Mughal painting had already established a refined courtly aesthetic under Akbar and Jahangir, the Rajput kings cultivated a parallel idiom — deeply rooted in indigenous themes, Hindu iconography, and local folk traditions.

These paintings were often created for royal patrons who commissioned works to adorn palace walls, illustrate literary manuscripts, or preserve courtly rituals and mythologies in pictorial form. The ateliers (chitrashalas) attached to Rajput courts were teeming with artists who transmitted their skills from generation to generation. Though influenced by the Mughals in technique — especially in naturalism, perspective, and figuration — the Rajasthani miniature paintings maintained a raw, lyrical quality that echoed local customs, epics, and devotional practices.

The Major Schools of Rajasthani Miniature Painting

Rajasthani miniature painting comprises several regional schools, each evolving in a particular kingdom and reflecting the aesthetic, cultural, and political ethos of its court. The major schools include:

-

Mewar School (Udaipur)

-

Marwar School (Jodhpur and Bikaner)

-

Bundi-Kota School

-

Jaipur (Amber) School

-

Bikaner School

-

Alwar and Kishangarh Schools

Each school presents a unique confluence of bold lines, vibrant color palettes, and thematic devotion, often focusing on the stories of the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Bhagavata Purana, Ragamala series, and portraits of royalty and nobility.

Analysis of Ten Representative Miniature Paintings

1. "Rama and Sita in the Forest" – Mewar School, 17th Century

|

Ms Sarah Welch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

This painting is the Kangra style of miniatures, a chitra style that developed in the Himalayan foothills. Painter: unknown Indian artist. Year created: 1780 CE, Medium: Opaque watercolor on paper, Size: 21 cm x 15 cm approximately

The use of vibrant yellow and crimson contrasts with the green foliage and suggests both emotional intensity and divine aura. The painter’s naive yet symbolic representation of trees and animals reveals an indigenous approach untouched by the then widely prevailing Mughal realism, emphasizing storytelling over naturalism.

2. "Ragamala: Bhairava Raga" – Bundi School, Early 17th Century

Part of the musical-themed Ragamala series, this painting embodies the terrifying Raga Bhairava, personified as a fierce ascetic flanked by dogs in a twilight landscape. The Bundi school is known for its lyrical depictions of nature and architecture, seen here in the stylized clouds, water, and domed shrine. The dynamic brushwork and saturated indigo sky give the painting a dramatic force, while the figure’s posture and iconography reflect tantric associations. The blend of music, devotion, and painting is strikingly synesthetic.

3. "Maharana Pratap at the Battle of Haldighati" – Mewar School, 17th Century

4. "Radha Meeting Krishna in the Forest" – Kishangarh School, Mid-18th Century

|

Detroit Institute of Arts , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

This painting, attributed to the artist Nihal Chand, exemplifies the poetic refinement of Kishangarh art. Radha’s elongated neck, lotus eyes, and delicate profile reflect an idealized feminine beauty.

The subdued pastel palette — pale pinks, jade greens, silver blues — evokes moonlight and emotional longing.

The composition’s vertical harmony and refined ornamentation mirror the court’s aesthetic sophistication under Raja Sawant Singh, himself a poet-devotee.

5. "Procession of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II" – Jaipur School, 18th Century

|

Barkhaharlalka, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

The Jaipur school blends Mughal realism with indigenous narrative rhythm.

Here, the painter employs meticulous detailing of textiles, jewelry, and architecture. The perspective is stylized, yet the spatial arrangement conveys depth.

The artist’s attention to ceremonial objects — parasols, musicians, standards — reflects Jaipur's ritualistic court culture and emphasis on order.

6. "Royal Court Scene at Bikaner" – Bikaner School, 17th Century

Bikaner miniatures are celebrated for their Mughal-influenced naturalism and refined line. In this court painting, the Bikaner raja is shown receiving envoys in an ornate pavilion. The figures are painted with delicate brushstrokes, and their garments show rich brocades and embroidered sashes. The architectural elements — jharokhas, cusped arches, floor patterns — echo Mughal aesthetics. However, the spiritual tone is subtly conveyed through symbolic placement: the central figure sits on a raised platform surrounded by attendants, emphasizing hierarchy.

7. "Hunting Scene with a Tiger" – Kota School, Early 18th Century

The Kota school, an offshoot of Bundi, is renowned for its dynamic action scenes. This painting portrays a chaotic royal hunt: elephants, horses, dogs, and spearmen converge upon a tiger in mid-leap. The sense of motion is heightened by sweeping curves, diagonal lines, and overlapping figures. The intensity of orange, red, and black reflects the violence and excitement of the hunt. Kota artists mastered the use of dense visual layering to create drama, energy, and spectacle.

8. "Baramasa Series: Month of Sharavan (Monsoon)" – Marwar School, 18th Century

|

Cleveland Museum of Art , CC0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Marwar paintings, often bold and rustic, express the spirit of folk narrative.

In this Baramasa miniature, the rains of Sharavan are shown as dark clouds and torrential rivers while women dance and swing under trees.

The theme is romantic longing and fertility.

The painter uses large patches of blue and green, depicting rain not as realism but as emotional force.

The naive representation of nature gives it a childlike vitality and directness.

9. "Krishna Lifting Mount Govardhan" – Nathdwara Pichhwai, 18th Century

|

National Museum , Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

This depiction of Krishna lifting the mountain to shelter villagers from Indra’s wrath is rich in symbolic motifs — peacocks, cows, lotus flowers — arranged around a dominant central figure.

The crowded composition and symmetrical layout signify divine protection and cosmic order. Bright orange, red, and gold convey both drama and sacredness.

10. "The Lovers in a Palace Garden" – Alwar School, Early 19th Century

One of the lesser-known yet refined styles, Alwar miniatures feature soft modeling and European-influenced shading. This romantic painting shows a royal couple reclining in a moonlit garden. The faces are tenderly expressive, and the night sky is painted with subtle gradations. Western perspective mingles with Indian symbolism — lotus ponds, parrots, jasmine trees — to create a harmonious blend. The result is an emotionally rich and visually intricate composition that reveals the late flowering of miniature art.

Thematic Richness and Techniques

Across these diverse examples, some unifying characteristics of Rajasthani miniature painting become evident:

-

Themes: Religious epics (Krishna, Rama), heroic legends (Rajput warriors), romantic poetry (Baramasa, Ragamala), daily life, and courtly grandeur.

-

Techniques: Use of natural pigments — vermilion, lapis lazuli, gold leaf — applied in layers. Fine squirrel-hair brushes were used for minute detailing, often in the eyelashes, jewelry, or embroidery.

-

Format: Typically painted on handmade paper, sometimes mounted on cloth, and often created as part of albums, manuscripts, or wall hangings.

-

Color and Form: Bold primary colors, flat compositions, symbolic landscapes, decorative borders, and hierarchical scale to denote divine or royal status.

Patronage, Legacy, and Preservation

The Rajput courts were not just consumers of art but active participants in its creation and conservation. Kings such as Maharana Jagat Singh of Mewar or Raja Sawant Singh of Kishangarh were themselves poets and connoisseurs who encouraged new artistic forms, patronized specific artists, and established permanent painting workshops. The integration of painting with poetry, music, and ritual life made it an intrinsic part of the cultural fabric of these courts.

The decline of royal patronage in the 19th century — due to British colonization and modernization — led to the disbanding of many ateliers. However, the legacy of these paintings endured, thanks to the efforts of collectors, museums, and art historians. Today, these miniature paintings are housed in major institutions like the National Museum (Delhi), City Palace Museum (Udaipur), and private collections worldwide.

Conclusion

Rajasthani miniature painting is a glorious embodiment of India’s visual imagination — deeply narrative, emotionally evocative, and richly symbolic. Under the patronage of Rajput kings, it grew into an art form that was both personal and public, devotional and heroic, intimate and majestic. Whether portraying the divine love of Radha and Krishna, the valor of Maharana Pratap, or the changing moods of the monsoon, these paintings reveal a world where line and color become vehicles of devotion, memory, and identity.

By studying and preserving this intricate art form, we not only honor the aesthetic achievements of the past but also recover a tradition of storytelling that continues to resonate with the cultural soul of India.