|

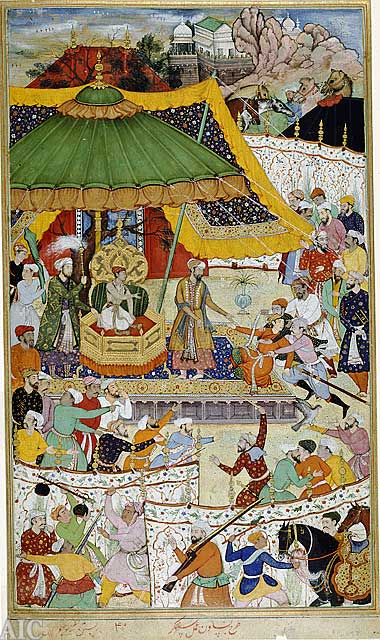

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Babur. Miniature from Bāburnāma |

Image the same boy, when he became a young man and conquered the city of Kabul (1504). The present-day capital city of Afghanistan. There he also failed. He lost his important small kingdom of Samarkand three times.

People thought he was finished. Forever. He did not rest. He assembled his small army and invaded the Indian territories of Punjab and Delhi. He defeated the weak king, Ibrahim Lodi, sitting on the Delhi throne (1526). Thus the boy who lost his father and kingdom at the age of twelve, the young man who lost regained his kingdom thrice, became the first Emperor of the Mughal Dynasty. Yes, his name was Babur (1494-1530).

Miniature Paintings of the Baburnama: A Journey Through Art and History

You open the Baburnama, and you are immediately transported into the 16th century—a world where empires rise, armies march, gardens bloom, and rivers carry the weight of history. This is not just a book. It is the life story of Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire in India. You follow him from the rugged valleys of Ferghana, through battles and exiles, until he finally claims the throne of Hindustan.

As you read his words, you notice that Baburnama is more than a political chronicle—it is a deeply personal diary. Babur writes not as a distant monarch but as a human being, reflecting on victories and losses, on the beauty of a flower or the song of a bird, with the same intensity as he describes a battlefield. Originally written in Chagatai Turkish, his memoirs reveal a mind that appreciates both the art of war and the art of living.

And then, you turn from text to image, and your journey deepens.

The Marriage of Literature and Visual Art

|

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Khusrau Shah swearing fealty to Babur. Miniature from Baburnama. State Oriental Museum, Moscow. |

You imagine holding in your hands not just Babur’s words but the illustrated manuscript commissioned by his grandson, Emperor Akbar, in the late 16th century.

Here, the Baburnama comes alive in miniature paintings—vivid, intricate, and breathtakingly detailed.

These are not casual decorations. Each painting is a historical window, showing you the rivers Babur crossed, the gardens he designed, the animals he observed, and the battles he fought.

You begin to see the union of literature and visual culture—Babur’s literary vision fused with the craftsmanship of Indian miniature painters.

The result is a confluence of Central Asian, Persian, and Indian traditions—a style we now recognize as Mughal Miniature Painting, born in Akbar’s court but destined to influence generations.

Understanding the Literary Canvas

As you follow Babur’s narrative, you realize his memoir is structured less like a royal proclamation and more like a journal kept during restless nights. He writes of military campaigns and political intrigues, but also of dreams, music, poetry, and gardens.

Unlike later Mughal emperors who ruled from established palaces, Babur’s life was defined by movement. He was a warrior-poet—fighting battles by day and composing verses by night. This dual nature—pragmatic yet romantic—gave his words the richness that artists under Akbar could translate into visual form.

You see how his attention to detail—describing the slope of a mountain, the taste of a fruit, the song of a bird—provided the perfect material for painters eager to bring his world to life.

The Art of Mughal Miniature Painting

|

Govardhan, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons Abu'l-Fazl presents Akbarnama to Akbar Chester Beatty Library |

You learn that the school of Mughal Miniature Painting began during Akbar’s reign, with the Baburnama as one of its key projects.

These miniatures were small—often no more than 5x5 inches—yet they carried immense visual power.

When you look at one, you see more than color on paper; you see the precision of tiny brushstrokes, the brilliance of reds, blues, and golds, and the meticulous rendering of each figure and landscape. Despite their size, these paintings feel larger than life.

You notice that many early miniatures depicted courtly life, hunting scenes, and epic battles—subjects that reflected the power and prestige of the Mughal dynasty. But the Baburnama miniatures also expanded beyond that, embracing landscapes, wildlife, and moments of quiet beauty.

Art in the Service of the Court

As you explore more, you understand that this art form was court-bound. The Mughal emperors sponsored the painters, providing workshops, materials, and patronage. This meant the paintings primarily reflected imperial interests rather than scenes from common life.

In the early period, you rarely find a farmer’s market or a village festival in these works. Instead, you see emperors on horseback, grand processions, royal hunts, and majestic architecture. The focus was on preserving imperial memory—turning moments from the ruler’s life into timeless art.

Realism and Symbolism in the Baburnama Miniatures

When you study the Baburnama miniatures closely, you see something unique: a shift toward realism and narrative depth that was less common in earlier Persian works.

The painters did not just illustrate Babur’s words; they extended his storytelling. Look at the landscapes—they reflect actual topography. Forts resemble their real counterparts. The animals—elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, cranes—are painted with astonishing ethnographic accuracy.

Some scenes are stylized, yet others offer surprising perspective and depth, even shadow. You sense the collaboration—one artist painting faces, another trees, another buildings—all working together under the direction of Akbar’s imperial atelier. It’s like a visual orchestra where each painter plays a different instrument.

The Indian Touch: Nature in Miniature

You notice something else—something distinct from the Persian tradition. The Baburnama miniatures embrace Indian naturalism. Here, squirrels leap through branches, peacocks and peahens display their feathers, fish swim in clear water, and demoiselle cranes stride through fields.

These natural elements were not common in earlier Persian manuscripts. Their inclusion in the Baburnama is a distinctly Indian contribution, adding richness, variety, and charm. You feel the painters’ relief as they take a break from endless depictions of war to paint a bird in flight or a flowering tree.

The Freedom to Explore New Subjects

As Mughal art evolved, painters under Akbar began to explore subjects beyond the emperor’s exploits. You start to see portraits of beautiful women—often imperial consorts or Rajput queens—rendered with care and grace. Court life expands to include music, poetry, and leisure.

Yet, in the Baburnama, the blend remains balanced—there is still the thrill of battle alongside the serenity of a riverside garden. This variety reflects Babur himself: a ruler who built empires but also planted orchards.

Experiencing the Baburnama as You

As you turn the pages—whether in a museum exhibition or a high-quality reproduction—you begin to see the Baburnama not only as history but as a living conversation between text and image.

You feel Babur’s presence in the words, and you see his world in the paintings. You notice how the visual details confirm, expand, or even subtly reinterpret what Babur wrote. You realize you are witnessing not just a historical document, but a cross-cultural masterpiece where literature and art meet.

The Legacy of Baburnama Miniatures

When you step back, you see how the Baburnama miniatures helped shape the future of Indian art. They became a model for later Mughal works and inspired Rajput courts to commission their own variations.

The influence extended far beyond the 16th century. Even today, art historians, collectors, and admirers of world heritage look to the Baburnama as an example of how visual and literary storytelling can merge into something timeless.

And you—having journeyed through its words and images—carry a piece of that legacy with you.

A strange combination. Emperor Babur was a poet and an extensively learned man. Even during his battling life, he kept his literary spirit in active mode. Here is a miniature from the illustrated book Baburnama, wherein it depicts the war scene.

Babur had invaded India with a horde of 12000 horses. In the battle of Panipat, he had got a decisive victory and put up the foundation stone for the Empire in India. This is the medieval history of India.

About the subjects painted in the miniature paintings, the miniature artists had handy subjects: the court scenes, the meetings of the Emporer with their court men and other kings. They were mainly occupied with the depiction of the life of their sponsor emperors and kings. Here is a scene from Babur's court. A king or a prince who conceded defeat or came voluntarily under Babur’s rule is shown here swearing loyalty to Babur.

Indian Miniatures: Subjects and Themes: The miniature style of paintings in

Indian Miniatures: apart from the scenes from ordinary life, mainly depicted scenes from Mughal Court. The subjects like animal paintings and vegetation depictions were yet to come. These subjects found their place only after Emperor Akbar took over the reign.

The paintings available from this spell are generally done on palm leaves, as the paper was not in use.

With the use of paper in miniature paintings from the early 14 century, the artists of the Indian miniature style adopted the same. So the work onward that era is on paper.

Hindu Mythology in Miniatures: Once Emperor Akbar was on the throne of the Mughal Dynasty, he started taking interest in the indigenous culture of India. He helped the local artists to paint, sing and write poetry. He also helped miniature painting type of paintings to prosper during his reign. These miniature artists adopted mythological stories as their subjects of the painting. These artworks were generally accompanied by religious manuscripts' text and mythological epics' illustrations. Other subjects like portraits and scenes from the daily life of the people were still not popular among the miniature artists. However, once the miniature art percolated into the deeper regions of India, the subjects started to pour in.

|

See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons |

Squirrels, a Peacock and Peahen, Baburnama

Before 1530

Natural scenes and flora and fauna were the new concept in the art of miniature painting, till the art reached other regions of India. Such newer and innovative themes and subjects got their due place on the frames of the artworks. Thereafter a period came wherein the paintings depicting mythological scenes from Hindu scriptures were becoming the subjects of miniature paintings. This painting is a Dodo illustration by Ustad Mansur.

While looking at the Indian miniatures we can draw a conclusion that these

paintings resemble the Persian style of painting. It is so because the artists

who did Mughal era paintings in India had got training from the

painters who migrated from Persia, today’s Iran.

Unlike most of the Persian paintings in Baburnama, the painters have

developed their taste for painting scenes of nature, too. Here the Miniature

shows a landscape with Squirrels, a Peacock and Peahen, Demoiselle Cranes, and Fishes. It has enhanced the value of the miniatures, as the artists were

interested in painting landscapes, too, in addition to the war scenes and love

scenes. [All the above paintings are in Public Domain, taken from

Wikimedia Commons]