|

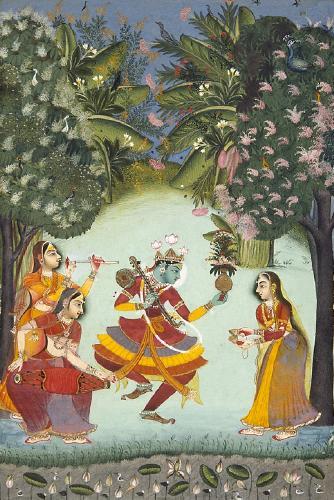

Rajput, Kota, Rajasthan. Opaque watercolour with gold on paper. Art Gallery of New South Wales, Australia |

For this storied land, steeped in the legendary valour of Rajputana's heroes, has long been a fertile sanctuary, a vibrant heart pumping the very lifeblood of Indian painting across the ages.

Here, art is not a cloistered relic confined to hushed gallery walls, but a living, breathing entity, adorning the very soul of the landscape and its people.

Picture the sun-drenched courtyards, where the vibrant hues of rangoli dance underfoot, the very walls of homes whispering ancient tales in the eloquent language of pigment and line, each delicate brushstroke a testament to the boundless wellspring of creativity that has forever blossomed within these desert abodes.

The Art of the Miniatures

Behold these exquisite jewels, held delicately within the palm, each a meticulously crafted universe, a window into realms both earthly and divine. These are perhaps the most intimate and captivating whispers of Rajasthan's profound artistic spirit, a unique and luminous bloom in the sprawling, fragrant garden of Indian art. From the nascent dawn of the sixteenth century, a chorus of distinct artistic voices arose, each a school of painting unfurling its petals in its own inimitable hue and form. Lean in closely, and you can almost hear their venerable names echoing across the corridors of time: the regal and majestic Mewar, the spirited and dynamic Bundi-Kota Kalam, the grand and opulent Jaipur, the serenely luminous Bikaner, the dreamlike and ethereal Kishangarh, and the boldly expressive Marwar. These names, like resonant echoes of ancient kingdoms and their noble patrons, indelibly mark the very soil where these rich artistic traditions took root, flourished, and continue to inspire.

Ragmala Paintings

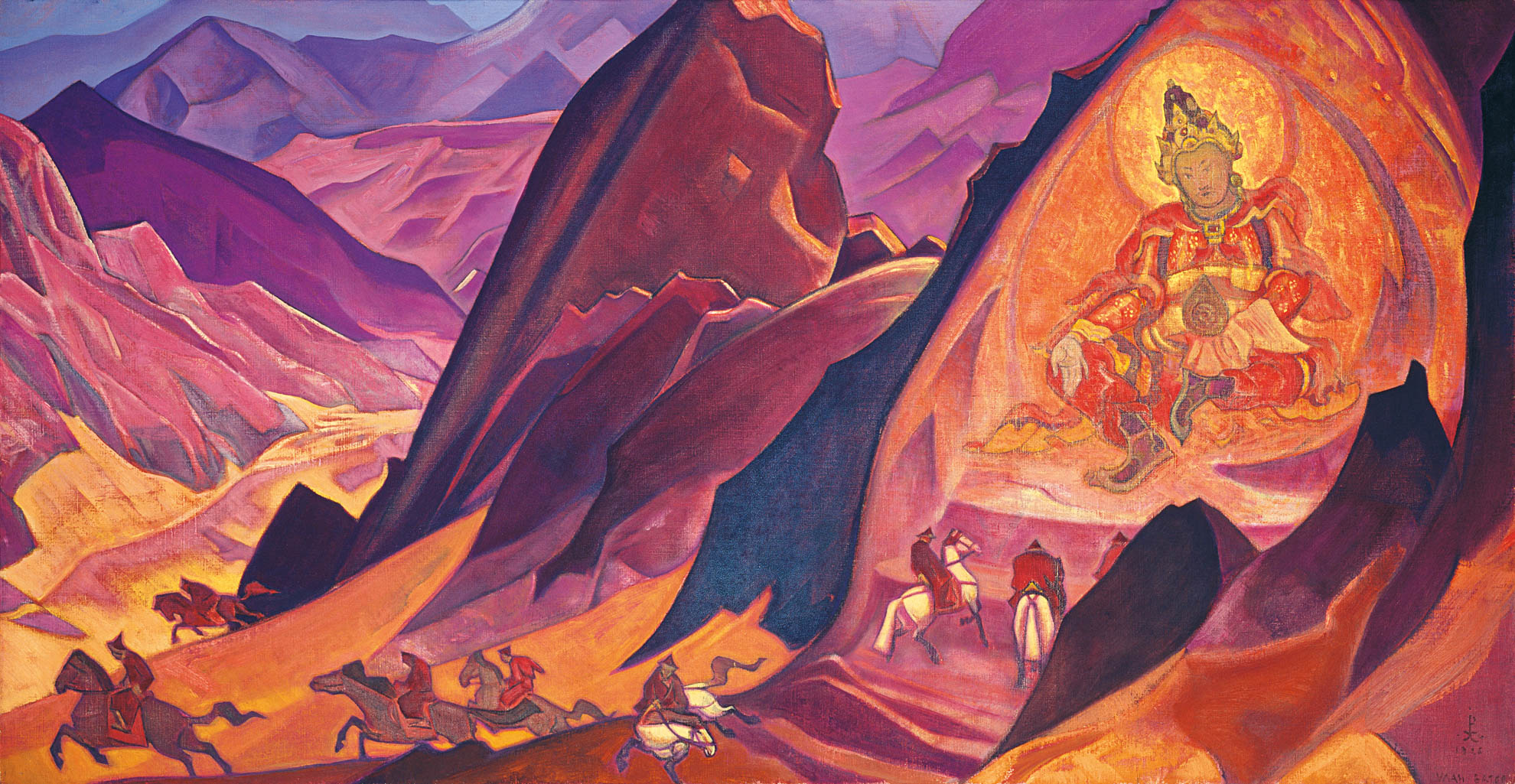

Consider the Ragmala, not merely a series of paintings, but a garland woven not of transient blossoms, but of timeless melodies themselves. These are visual symphonies rendered in vibrant pigments, each delicate brushstroke a note vibrating with the very essence of a classical Indian raga.

The artist transcends the role of mere painter, becoming a conduit, a sensitive translator who captures the very soul of the music onto the enduring surface of paper, immortalising the emotions it evokes, the subtle nuances of its atmosphere, the profound depths of its feeling. As the fervent tide of Vaishnavism, a deeply devotional sub-sect of Hinduism, swept across the land in the early eighteenth century, a radiant new dawn broke on the horizon of artistic inspiration. The epic and enchanting tales of Hindu mythology, particularly the lyrical and passionate narratives of the Gita Govinda, became a sacred wellspring, a boundless source for the artist's fertile imagination. Across the sun-kissed plains of Rajasthan and the neighbouring lands of Gujarat, these sacred verses blossomed anew, transforming into vibrant pictorial narratives that graced not only the delicate surfaces of miniature paintings but also found expression in other art forms, their beauty even whispering its way into the distant, mist-shrouded hills of Pahari.

Indian Schools of Painting:

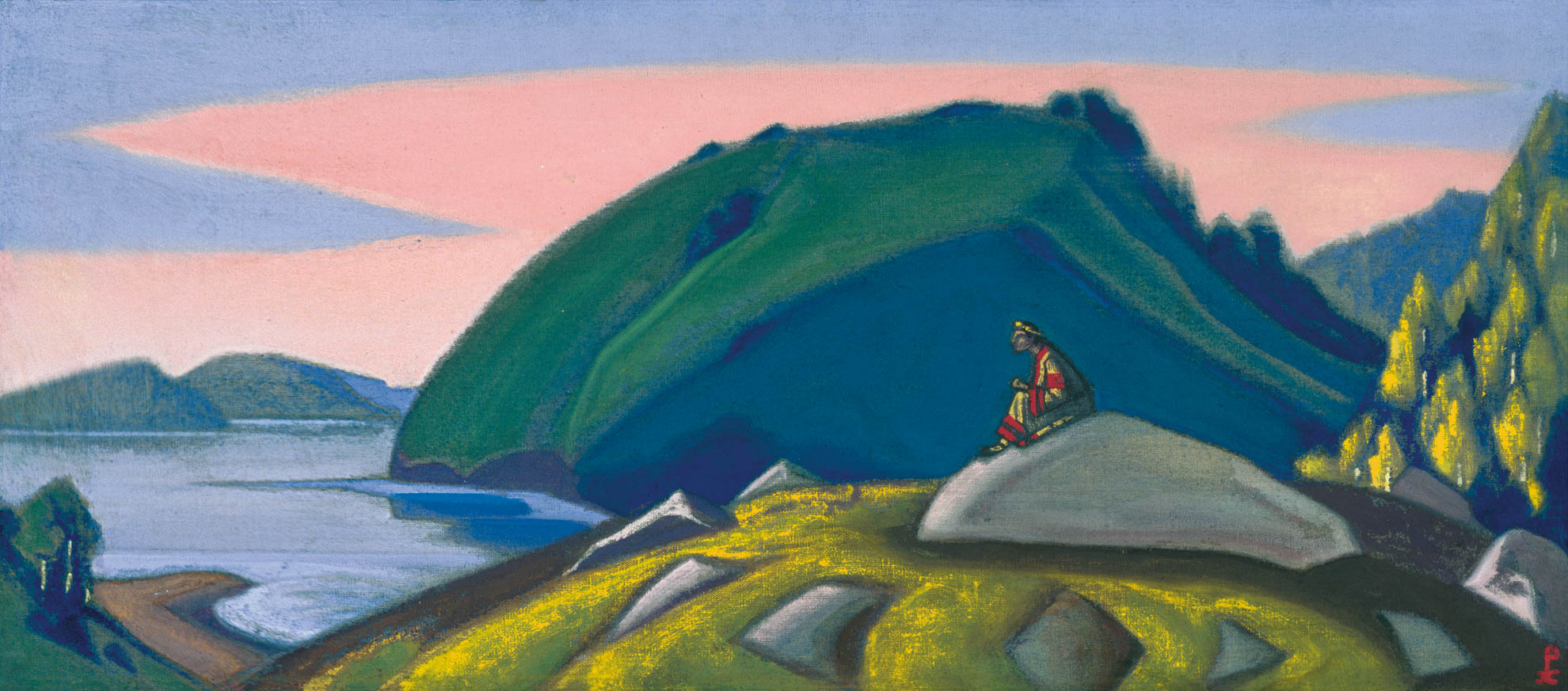

Now, let your gaze linger upon the distinct artistic dialects spoken by each of these remarkable schools of painting. In the verdant realms of Kota-Bundi, the very canvas seems to breathe with the palpable lushness of flowing rivers teeming with life, the dense and protective embrace of emerald forests echoing with birdsong, and the gentle, undulating sway of grassy fields stretching towards the horizon – a vibrant and heartfelt ode to their bountiful natural world.

Some artists, with a keen and observant eye for the unfolding drama of the hunt, immortalised the thrilling chase, the taut energy of the pursuit frozen in time, while others captured the raw and untamed power of animal combat, the clash of titans rendered in dynamic lines and bold colours. And the women who grace these captivating paintings? They are visions of ethereal grace, their forms imbued with a timeless elegance, their costumes flowing in harmonious proportions, adorned with intricate patterns and vibrant hues. Indeed, bright colours sing across these remarkable artworks, with the passionate and grounding presence of red often anchoring the composition, a fiery heartbeat pulsing within the visual narrative, drawing the eye and igniting the senses.

|

| Radha celebrating Holi, c1788. Kangra, India AnonymousUnknown author Victoria Albert Museum, London |

|

Paintings of Radha and Krishna As the devotional fervor of Vaishnavism unfurled across the land, the divine romance of Radha and Krishna blossomed into a muse for countless artists. Their forms, imbued with celestial grace, became the heart and soul of many a canvas, particularly within the intricate world of Rajasthani miniature paintings.

From the very

soil of Rajasthan emerged Rajput painting, a tradition steeped in heritage.

This exquisite style, adorned with beauty and imbued with poetic sensibility,

flourished as the seventeenth century waned and the eighteenth dawned. Drawing

inspiration from the delicate artistry of Mughal miniatures, the Rajputana, or

Rajasthan, paintings ascended to become a principal creative pursuit within the

regal courts of western India, each brushstroke echoing tales of valour,

devotion, and ethereal beauty.

Let us then, with hushed reverence, unroll the very fabric of

time, and behold not just a chronicle, but a living, breathing tapestry woven

with the ochre dust of valour and the shimmering threads of devotion: the art

of Rajputana. Across the sun-kissed expanse that once cradled kingdoms like

blossoming lotuses in a desert spring – Mewar, Marwar, Amber, Bundi,

Kishangarh, each a distinct jewel gleaming under the azure sky – a symphony of

artistic expression arose. Though each realm cultivated its own unique cadence,

its own instrumental voice in this grand, painted orchestra, a fundamental

harmony resonated through them all, a deep-seated melody echoing the soul of

the land.

The very canvases awakening, stirred by the epic breath of the

Ramayana, its heroes striding forth in hues as fiery as the desert sunsets that

paint the Aravalli hills ablaze. Feel the profound wisdom of the Mahabharata

unfurl in strokes as deep and contemplative as the sapphire expanse of the

night sky, dotted with the diamond dust of stars. And above all, let your gaze

be drawn to the eternal, enchanting spring of Lord Krishna's life, a perennial

source that nourished the very roots of their artistic imagination.

Witness the Lord Krishna's childhood pranks rendered with the

playful lightness of a desert breeze, his divine, yearning love for Radha

blooming in colors as tender as a monsoon cloud, his cosmic dances, which is

known as the Rasa Lila, swirling across the painted surfaces like celestial

dust motes caught in a sunbeam – each scene a devotional poem whispered in the

language of light and shadow, a hymn rendered in vibrant pigments.

These were not ephemeral sketches, dashed off in haste, but

cherished chronicles, imbued with the weight of tradition and the love of

generations. They were tenderly cradled within the gilded leaves, the albums of

immense value, treasures commissioned and held close to the hearts of royal

patrons, their very touch imbuing the artwork with a deeper significance. The

very walls themselves became boundless palimpsests, breathing with the vibrant

tales that unfolded within their embrace.

Picture the opulent chambers of majestic palaces, where sunlight

filtered through latticed windows, illuminating scenes of courtly splendor; the

secluded alcoves within formidable forts, their cool stone surfaces adorned

with narratives of bravery and sacrifice; and the sprawling courtyards of

the havelis,

the noble residences, their walls alive with the painted echoes of daily life

and grand occasions. Amongst these architectural marvels, the edifices erected

by the proud Shekhawat Rajputs stand as particularly luminous testaments, their

very stones whispering ancient stories through the exquisite artistry that

graces their facades, each fresco a silent storyteller.

These artistic legacies transcend mere decoration; they are

portals, shimmering windows that offer profound glimpses into a bygone era,

eloquently narrating the rhythms of life, the intricate tapestry of customs,

and the fervent aspirations that pulsed within the hearts of the people.

Observe with a discerning eye, and you will witness the stately processions of

the royal courts, their elephants caparisoned in jewel-toned fabrics, their

riders adorned in regal attire; the intricate rituals and ceremonies, each

gesture imbued with sacred meaning; and the very fabric of their daily

existence – the vibrant hues of their clothing, the tools of their trades, the

flora and fauna that surrounded them – all captured in meticulous and vibrant

detail. As the gentle, transformative tide of Vaishnavism, with its currents of

devotion and love, swept through the land in the early eighteenth century, a

new and fervent wave of artistic inspiration was ignited by the lyrical verses

of the Gita Govinda.

Gita Govinda: These sacred poems, celebrating the

divine and intensely human romance between Radha and Krishna, became a

veritable wellspring of creative energy, their verses blossoming into a

thousand painted forms, each a visual echo of the sacred text. Indeed, in certain

artistic heartlands of Rajasthan and the neighbouring lands of Gujarat, art

permeated the very air, becoming an inseparable thread woven into the fabric of

domestic life, adorning not just palaces and temples, but the very walls of

their homes, transforming the mundane into the sacred.

The enchanting melodies of the Gita Govinda, carried on the winds

of devotion, even resonated far beyond the arid plains, finding delicate and

evocative expression in distant schools of painting, such as the ethereal

Pahari style nestled in the Himalayan foothills, a testament to the enduring

power and universal appeal of these timeless and sacred narratives.

[All the above paintings are in Public Domain, taken from Wikimedia Commons]